Latest Reports

A Key Missing Piece of the Amad Puzzle: The Shahid Boroujerdi Project for Production of Uranium Metal & Nuclear Weapons Components

by David Albright, Olli Heinonen [1], Frank Pabian [2], and Andrea Stricker

January 11, 2019

PDF file of report

Annex 1: New Parchin Tunnel Maps

Annex 2: Contract

Annex 3: Ground Location Correlation

Annex 4: Table of Functions of Rooms

Annex 5: Parchin Tunnel Overlay

For a summary of this report, click here.

- Documentation from the Nuclear Archives reveals a major, former nuclear weapons site under Project 110 of the Amad Plan that was not previously identified. Project 110 was charged with the development and production of nuclear warheads;

- The most likely purpose of this site was as a production-scale facility to produce uranium metal components for nuclear weapons, fulfilling Iran’s long-time quest to acquire and develop uranium metallurgy and components suitable for nuclear weapon manufacturing;

- Satellite imagery analysis supports these findings;

- The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Board of Governors should urge the IAEA to verify sites, locations, facilities, and materials involved in these activities, and urge Iran to cooperate fully in these investigations.

Background

Documentation seized in January 2018 by Israel from the Iranian “Nuclear Archive”3 revealed key elements of Iran’s past nuclear weaponization program and the Amad program more broadly, aimed at development and production of nuclear weapons. The material extracted from the archives4 shows that the Amad program had the intention to build five nuclear warhead systems for missile delivery.5 A key step in the manufacturing of a nuclear warhead is the production of the fissile material components of a nuclear warhead. Such a facility would turn high enriched uranium hexafluoride (UF6) to uranium metal, cast it, and machine components to their final forms to be assembled in the warhead itself. Iran had a long quest to acquire uranium metal handling capabilities and some documentation related to such activities was found during the IAEA investigations into Iran’s past nuclear weapons program.6 Newly found material in the archives sheds more light on Iran’s goal of achieving a nuclear weapons capability within a short period of time, and provides key insights for today if Iran decided to renege on its obligations under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) not to build nuclear weapons.

Findings

On February 20, 2002, Sayed Shamsuddin Borborudi, then representing the Institute for Training and Research of Defense Industries (ITRDI) of Iran’s Defense Ministry, and Mr. Amir Hajizadeh, then of the Headquarters of the Aerospace Force of the Army of the Guardians of the Islamic Revolution (NAHSA), signed a contract to build a large, secret underground nuclear tunnel complex at the Parchin site, about 35 kilometers from Tehran.7 This project was part of what is called in the archive documents the “Amad8 Supraorganizational Plan,” Iran’s name for its nuclear weapons program in the early 2000s under the control of the Ministry of Defense, and in particular ITRDI.9 More specifically, this project was under Project 110, charged with developing and building nuclear warheads for ballistic missiles. Before the seizure of a portion of the Nuclear Archive, the fact that this site was part of the Amad project was unknown to the IAEA. This also suggests that most, if not all, Western intelligence agencies were also unwitting. According to senior Israeli officials interviewed in November 2018 by one of the authors, Israel was unaware that this site was connected to the Amad effort, until it saw these documents from the archive.10

This subproject of Project 110 was labeled in the Nuclear Archive documents as 14/3 or 3/14,11 with a specific code number of 36.12 It was given the code name of the Shahid (martyr) Boroujerdi project, after a martyr who was one of the founders of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and was killed during the Iran/Iraq war.13 Based on assessing the purpose of the individual halls of this underground facility and other archive information we have obtained, this site was probably for the large-scale production of uranium metal and the fabrication of uranium-based nuclear weapon components under Project 110. If true, this finding would answer a long-standing question that has eluded the IAEA and Western intelligence agencies about Amad’s production-scale uranium metallurgy efforts, a vital step in building a nuclear weapons arsenal.

Because this was a production plant large enough in floor area to make components for multiple nuclear weapons per year (see below), and not a research and development facility, its construction would also signify that Iran was likely further along in making nuclear weapons in 2003 and 2004 than typically posited. A decision to move ahead and build a production-scale plant would imply that Iran had gained confidence in making uranium components for nuclear weapons and was implementing a plan to build them in the near future.14 The construction of this site means that Iran’s nuclear weapons program did indeed advance further than the IAEA assessed in late 2015, just prior to the implementation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), when it asserted that a range of activities relevant to the development of a nuclear explosive device “did not advance beyond feasibility and scientific studies, and the acquisition of certain relevant technical competences and capabilities.”15 The existence of and plans for this site stand in sharp contradiction to that assessment.

The Shahid Boroujerdi project shows that key information about Iran’s nuclear weapons program was not known prior to the implementation of the JCPOA. Because this site was a production-scale facility, it reinforces the view that Iran is capable of building nuclear weapons more quickly than previously thought. U.S. and other officials have routinely talked about Iran needing a year or longer to fashion a deliverable nuclear explosive device, once it had enough weapon-grade uranium for one. The Shahid Boroujerdi project implies a much faster rate of weapons assembly than asserted in the lead up to the Iran nuclear deal.

The two signatories of the aforementioned contract appear to have gone on to become more senior officials in Iran’s ballistic missile and nuclear programs. Since 2009, Hajizadeh has been Commander of the Aerospace Force of the Army of the Guardians of the Islamic Revolution, known in the United States as the IRGC Aerospace Force and a vocal proponent of Iran’s missile prowess. Based on sanctions lists, Borborudi later became Deputy Head of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI). Both have been sanctioned under UN Security Council resolutions and European Union sanctions, but as far as the authors could tell, neither is listed on any U.S. sanctions list. The continuity of these and other senior officials in missile and nuclear organizations is a sobering reminder that key Iranian personnel from the Amad program remained highly influential after 2003 in the day-to-day activities critical to maintaining a capability to make and deliver nuclear weapons.

The current purpose and status of this site is unknown, although it is difficult to ascribe any nuclear use to it post-Amad, e.g. post-2004. It could have been repurposed to other military uses. Nonetheless, the site remains an enigma and deserves further scrutiny. Moreover, the archive contains a detailed plan to retain Iran’s nuclear weapons program post-Amad.16 Today, conclusive evidence that Iran has terminated its nuclear weapons program, albeit smaller in size than the Amad effort, is sparse to non-existent. Typically, the evidence presented in public that Iran’s nuclear weapons program ended in 2003 or 2004 depends on reciting the 2007 National Intelligence Estimate on Iran, which now appears incorrect on this point in light of the information in the archive. Moreover, the IAEA’s past reporting that it found no evidence of a nuclear weapons effort post-2009 reflects more on Iranian stonewalling and obfuscation, and in light of new information, means little given Iran’s on-going noncooperation on military nuclear issues, its refusal to grant access to relevant sites and personnel, and the information in the archive. Given its previous nuclear weapons fabrication subordinate to the Amad project, the tunnel complex and equipment already procured by Iran should be investigated to ensure that Iran is no longer involved in any undeclared nuclear-related activities.

The Shahid Boroujerdi project was to be outfitted with a range of dual-use equipment, materials, and technology relevant to making nuclear weapon components.17 The location of any such items is unknown, as is Iran’s current work, capabilities, or plans to make uranium metal and components for a nuclear weapons program. Overall, this new information adds more urgency to efforts to create an accurate, complete history of Iran’s nuclear weapons efforts and to obtain answers from Iran about the fate today of the equipment, material, technology, and personnel from the Shahid Boroujerdi project, and more broadly, the Amad and successor programs.

The information about a heretofore unknown Project 110 facility highlights the immense value of the Nuclear Archive seized by Israel in filling in missing pieces of the jigsaw puzzle that is Iran’s nuclear weapons program. It also highlights the urgent need for the IAEA to inspect previously associated military sites in Iran, and once again, provides substantial evidence that Iran’s declarations to the IAEA are incomplete and deliberately false.

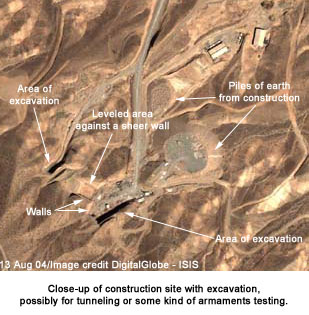

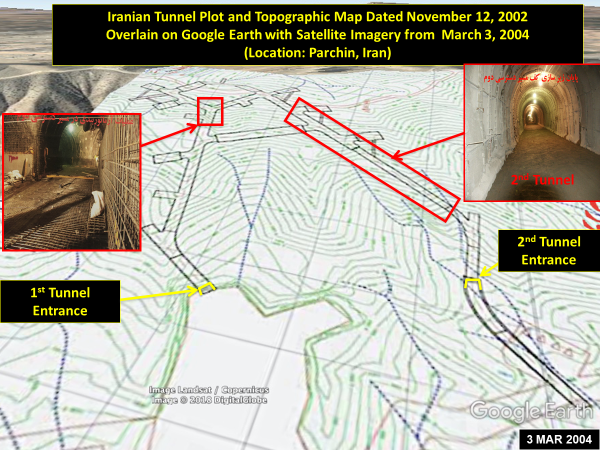

A Previously Unknown Amad Site

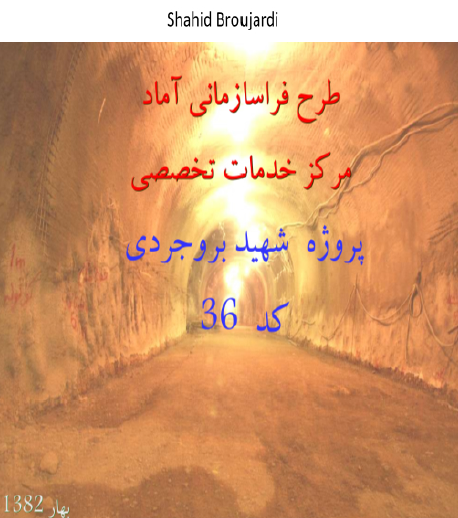

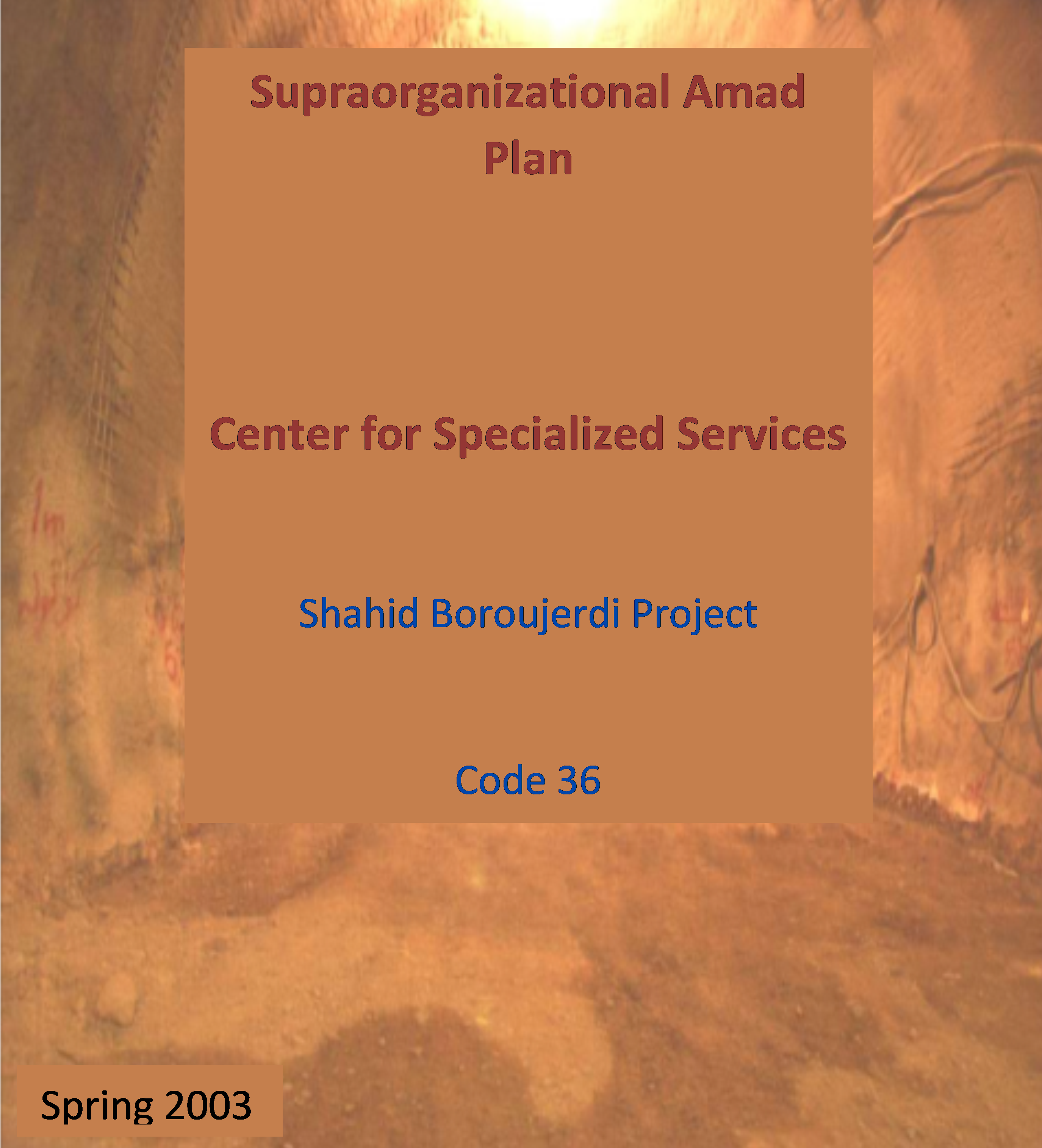

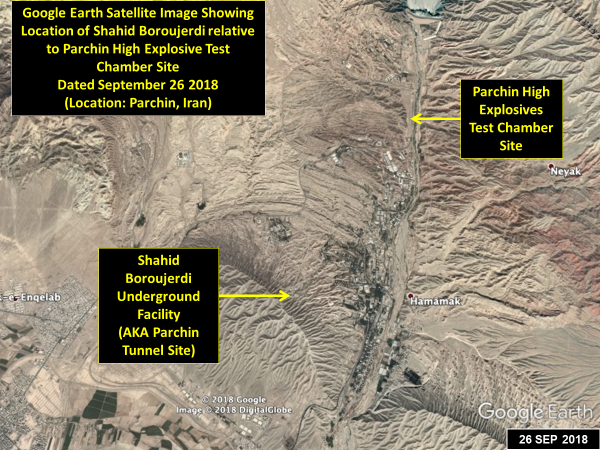

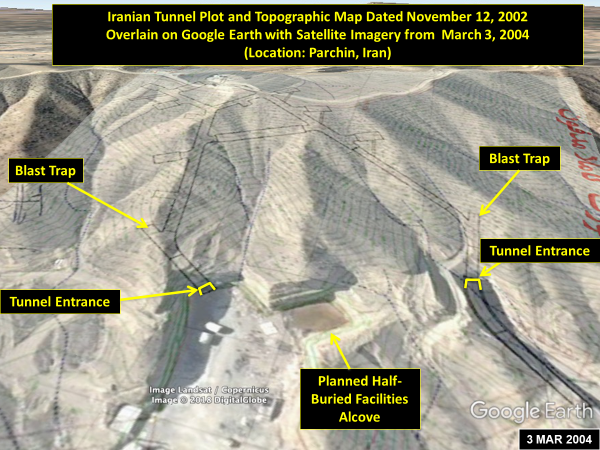

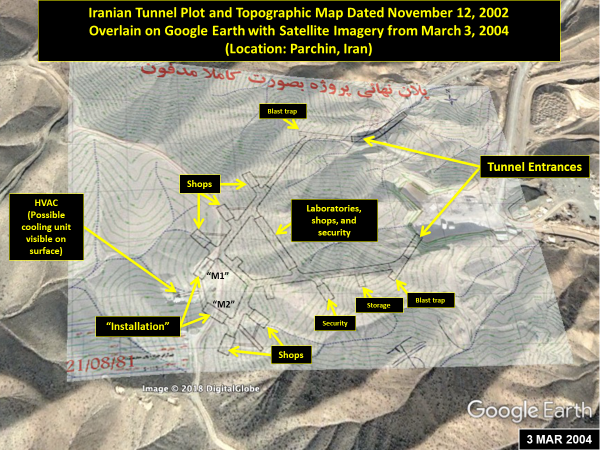

The Iranian Nuclear Archive, also called the Atomic Archive, contains a set of documents about the Shahid Boroujerdi project. The Institute obtained about 40 pages of documents from Israel, largely from an Iranian slide presentation on this project, which we have independently corroborated and assessed. Figure 1 is a cover sheet of an Iranian presentation dated spring 2003 about this Amad project, showing an interior photo of a section of the tunnel complex. Figure 2 shows the location of this site within the Parchin complex, based on a topographical map and a panchromatic satellite image of the site found in the Nuclear Archive. Annex 1 contains these two images overlain on publicly available Google Earth images, allowing the determination of the precise location of the Shahid Boroujerdi tunnel site, also called in the open literature the Parchin tunnel site. These two images were in a subsection of a presentation that was titled “Locating and Finalizing the Site.” Site selection of the project was completed January 23, 2002, according to this slide.

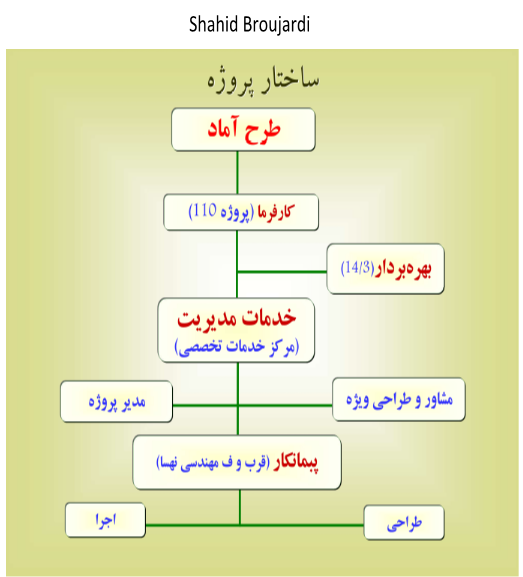

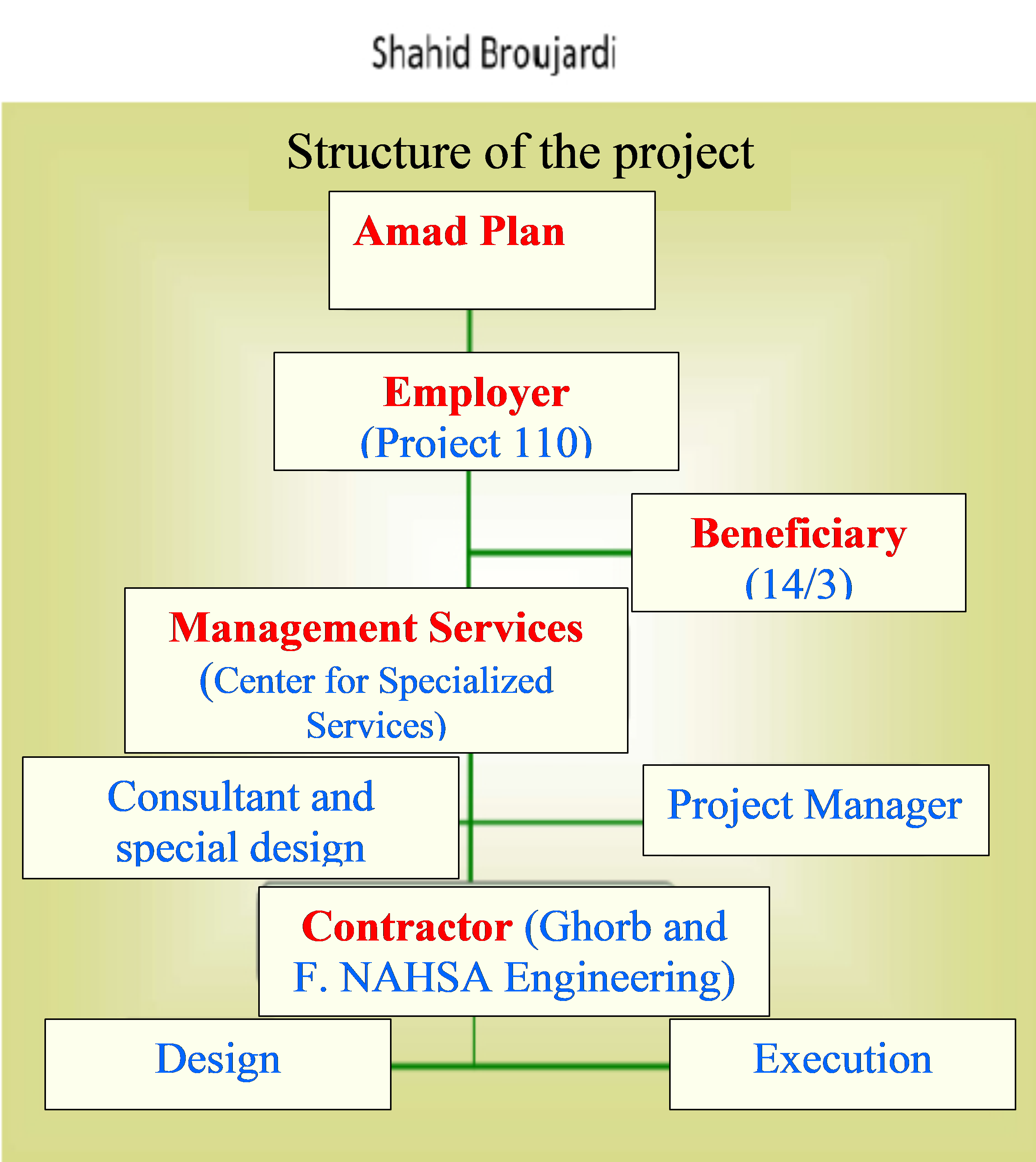

Figure 3 is another Iranian document from this presentation that shows the organizational structure of the Shahid Boroujerdi project, extending from the Amad plan at the top of the chart, to the “employer,” Project 110, and then downward to a management services entity called Center for Specialized Services (see also Figure 1). The Iranians refer to project 14/3, or the Shahid Boroujerdi project, as the “beneficiary.” The Center for Specialized Services appears to be some type of entity charged with overseeing the construction of this facility for the benefit of the Shahid Boroujerdi project; for example, the “Project Manager” is under this center, who in turn, is above the titles of consultant and special design. Under this center is the contractor for this project, Ghorb and F. NAHSA Engineering, charged with design and execution of the project. Ghorb appears to be another name for the NAHSA’s Construction Base of the Seal of the Prophets (Gharargah Sazandegi-ye Khatam al-Anbia), which is also known as Khatam-al Anbiya Construction Base. Ghorb has been designated as a sanctioned entity by the U.S. Treasury Department.18 No information has been found on F. NAHSA Engineering.19

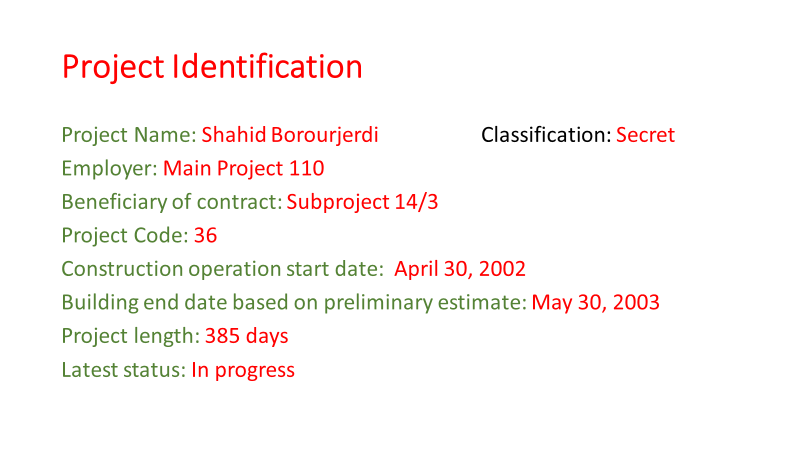

Figure 4 is an Iranian document that provides additional details about the Shahid Boroujerdi project. It states that at the time this chart was prepared, the project was in progress. It again states that the project’s employer is Project 110 and the beneficiary is subproject 14/3, with a code number of 36. Construction of this subproject started April 30, 2002 and was expected to end on May 20, 2003, after 385 days.

Two pages of the contract for the Shahid Boroujerdi project (code 36) are in the set of documents available to the Institute from the Nuclear Archive, and the language indicates that the contractor would be providing a turn-key facility, including installing the equipment. Annex 2 contains the original document and a translation. The contract is composed of these cover sheets and several attachments that are unavailable to the Institute. Annex 2 also contains an image of a cover sheet of a supplement to this contract, showing tunnel excavation equipment.

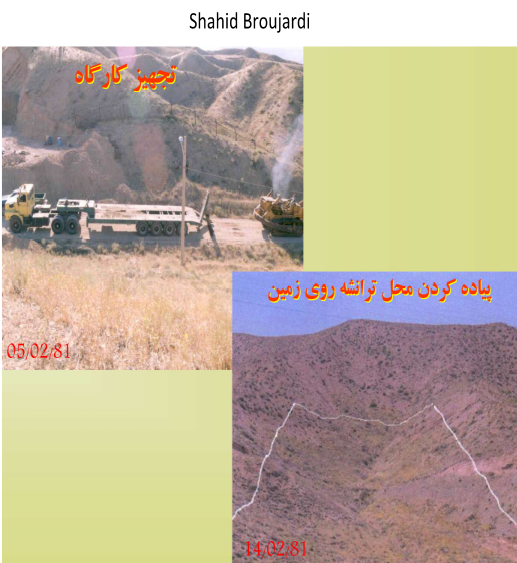

The documents show that the project was advancing quickly in 2002 and 2003. The contract was signed on February 20, 2002, only one month after site selection was finalized. The construction of access roads and outfitting the construction site commenced on April 19, 2002, according to the Iranian presentation. As noted above, construction of the tunnel complex started officially on April 30, 2002 but likely commenced a few weeks later. Figure 5 shows images of the site from the archive at the beginning of the construction project, date late April and early May 2002.

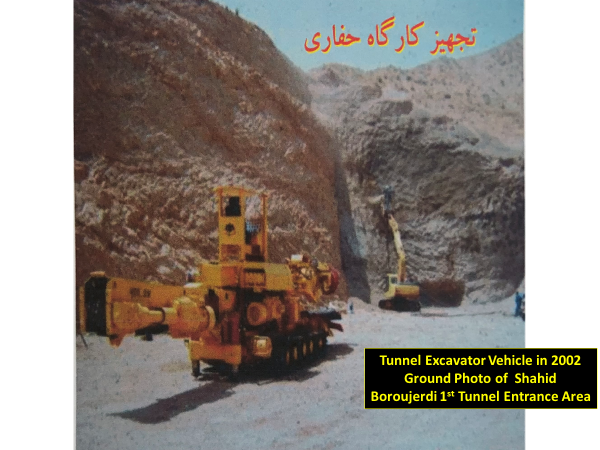

Figure 6 shows an undated ground photo of a tunnel excavator at the location of the main tunnel entrance; this same or a similar excavator can be discerned in a July 28, 2002, publicly available Google Earth satellite image of the same location. Using photographic analysis, Annex 3 correlates the location of the construction work in Figure 6 with the earlier ground photo from the archive, containing a white outline marking this same location (see Figure 5).

Site’s Purpose

Because this Amad project was directly under Project 110, the purpose was probably related to nuclear warheads. The project must have also been a critical one since it was highly secretive and protected, e.g. by being located in a tunnel complex. Moreover, it was a relatively large complex with many rooms planned.

The purpose of Project Shahid Boroujerdi was most likely the production and fabrication of uranium metal components for nuclear warheads. Although uranium is not directly mentioned in any of the documents available to the Institute, the most logical choice of materials to be handled in this facility is uranium.

This conclusion is partially supported by information from the reports of the IAEA. An Iranian project 3.14 was involved in shaping uranium metal. The nomenclature “project 3.14” is close to project 14/3, given that the placement of groups of numbers in Farsi can be reversed compared to English. Moreover, “/” in Farsi is a decimal point in English.20 Thus, project 14/3 can be interpreted as project 3.14.

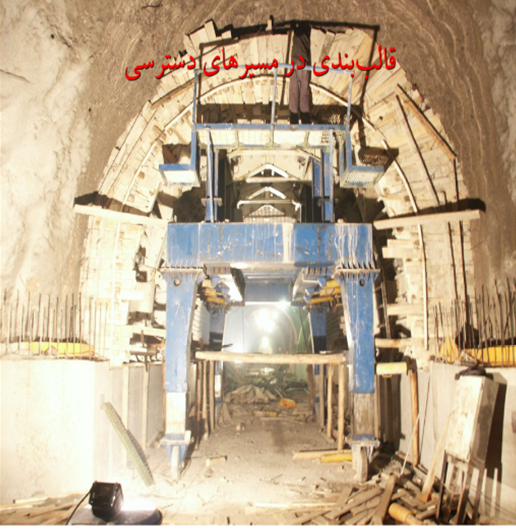

Senior Israeli analysts assess that this site was involved in making uranium metal components for nuclear weapons.21 In his April 30, 2018 presentation, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu showed a brief video from the archive of an underground tunnel facility. He said that this secret site was to produce “nuclear cores,” namely uranium components for nuclear weapons. Figure 7 is a frame-grab from this video in the archive made available by Israel to the media after the Prime Minister’s presentation, that shows tunnel construction and in particular the framing of a portion of the tunnel complex. For comparison, this type of framing operation is also shown in a Shahid Boroujerdi image available to the Institute (see Figure 7).

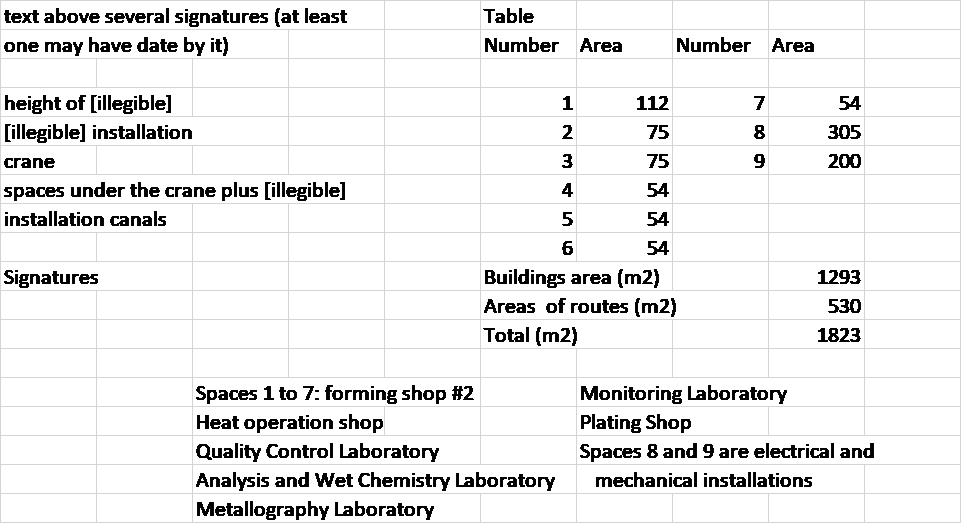

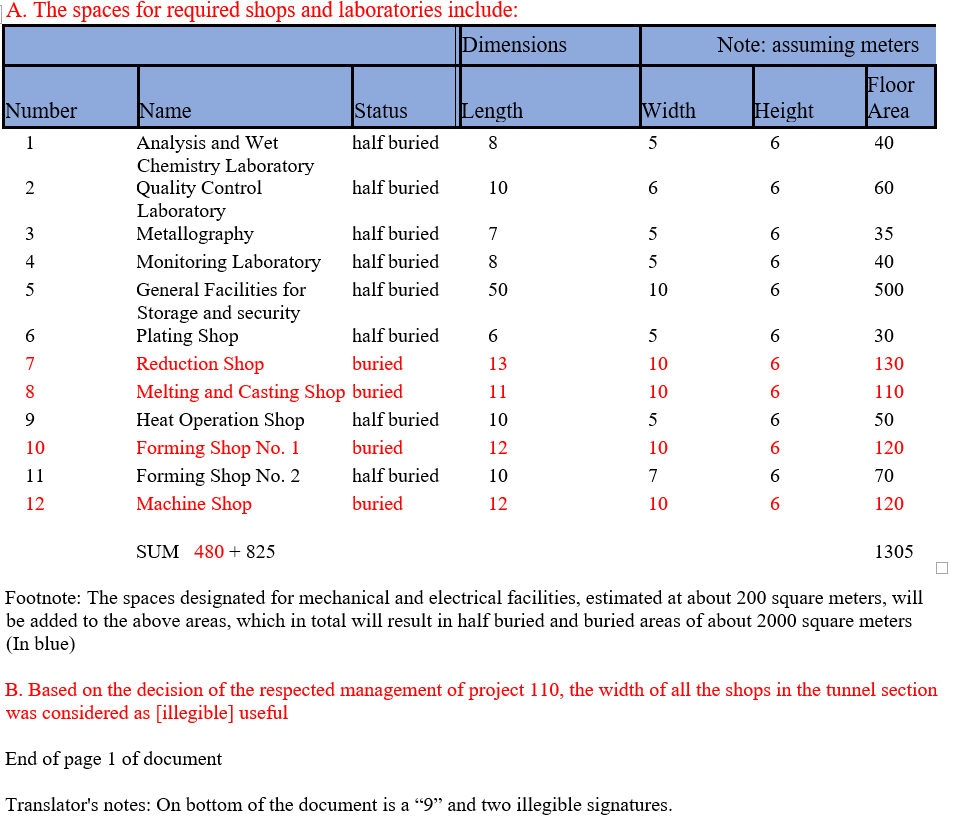

That the facility was being built to process metal is apparent in the documents. This can be deduced in particular from one of the documents, labeled as attachment 4 and titled the “Physical Program,” found in the section of the Iranian presentation that includes information on designing the site. It is a tabular description of intended rooms that was developed by the beneficiary, e.g. Project Shahid Boroujerdi, “based on the past correspondence, the negotiations of the meeting dated October 7, 2002, and the option selected by the honorable management of project 110.”22 Figure 8 shows a translation of this table (the original is in Annex 4 to this report). It lists twelve of the main halls in this facility, their purpose and physical dimensions, and whether they will be “buried” or “half-buried,” where buried means inside the tunnel and half-buried means placed into a cut-away hillside adjacent to the tunnel entrance. Key fully buried shops are dedicated to metal reduction, melting and casting, and metal forming. In addition, there is a fully buried machine shop. Reduction is a well-known process of producing metal. Half-buried areas include quality control, analysis and wet chemistry, monitoring, and metallography laboratories, and heat operation, plating, and metal forming shops. Thus, what appear to be the most sensitive areas, called shops, were all, except one, to be buried inside the tunnel.

The descriptions in this table in Figure 8, in the context of a Project 110 facility, suggest processes to make uranium metal and then melt and cast it into shapes for nuclear weapons. For example, a common method for the production of uranium is the reduction of uranium tetrafluoride with a metal, where a solid piece of uranium metal is obtained under a cover of slag. The process often entails taking a compacted mixture of uranium tetrafluoride and magnesium and putting it into a refractory-lined steel vessel, which is sealed, and heated until the reactants ignite (at about 650 degrees centigrade). After the reaction, the vessel is cooled to room temperature and the resulting metal “button” or “derby” is removed. If necessary, slag, or the other reaction products, are removed from the uranium metal piece. Subsequently, this uranium metal would be melted in a vacuum induction furnace and poured into molds. Afterwards, the cast pieces would be finished on other equipment. Finally, uranium metal components potentially exposed to the air would likely be plated to protect against the oxidation of the highly reactive uranium metal. Laboratories for quality control, metallurgy, and chemical analysis would be located nearby.

The Physics Research Center, the predecessor of the Amad plan, is known to have sought vacuum induction furnaces in Europe in the 1990s with the capability to handle uranium metal.23 Whether such a furnace was deployed in the Shahid Boroujerdi project is unknown. Israeli briefers stated in November 2018 that Iran had acquired at least components of vacuum induction furnaces for use in this facility.

The documents do not state where the finished uranium components would have been sent. However, tables in the archive suggest that an assembly facility was being planned and built in parallel.

Site Layout

Under the section of the document on designing the site, the Shahid Boroujerdi document set contains several internal plans of the site and additional brief descriptions of individual halls in the facility. The plans show a tunnel complex composed of a series of buried halls inside the tunnel and half-buried halls directly outside the main tunnel entrance, which was subsequently augmented with a second tunnel entrance in the final plan.

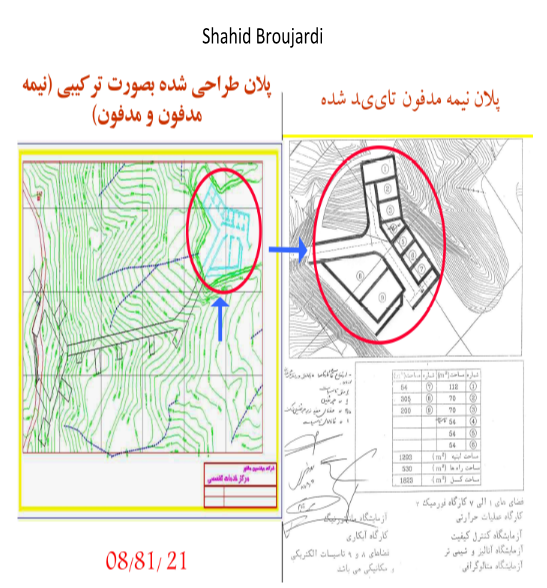

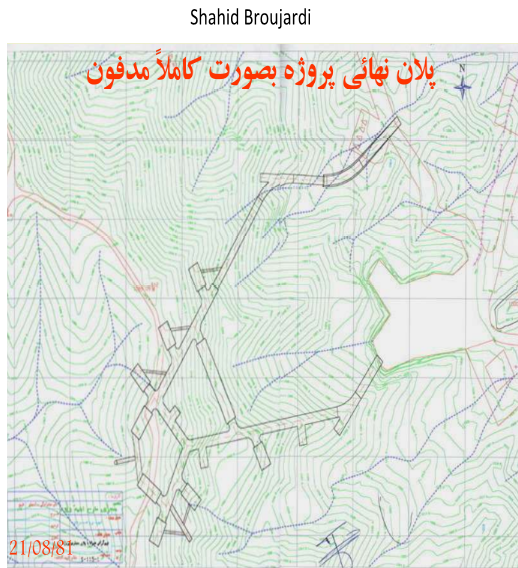

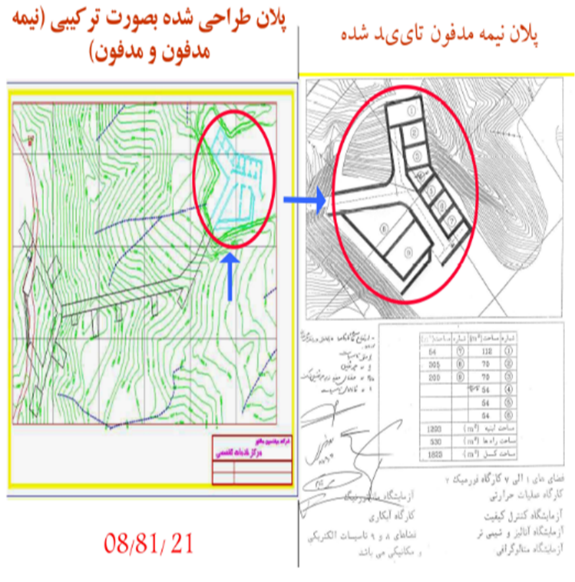

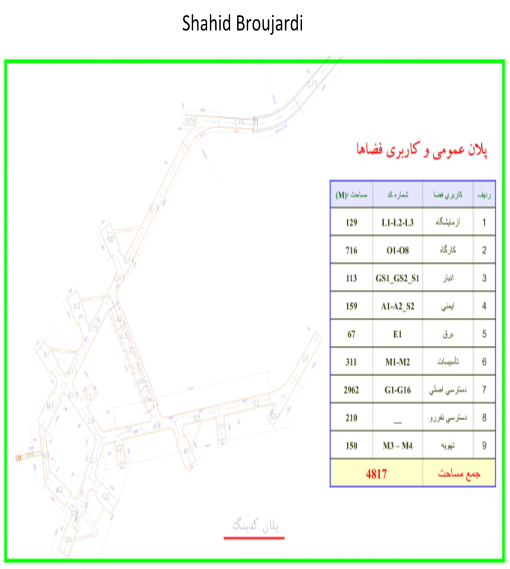

The rooms in the facility are described in two design plans, or plats, both dated November 12, 2002. In order of their presentation in the Iranian document set, Figure 9 shows the design plan for the facility in a “hybrid manner” with both half-buried and fully buried halls, with a single tunnel entrance, and Figure 10 shows the “final” plan for the facility containing rooms in a fully buried manner.

A translation of the text on the hybrid plan is included in Figure 11, showing the functions of the half-buried rooms, which match exactly the descriptions of the half-buried rooms described in the document in Figure 8. It is unclear if the plans in Figures 9 and 10 are complementary or alternatives. In the former case, the plan in Figure 10 would represent a design with all of the halls in the tunnel complex, namely representing a decision not to have both buried and half-buried rooms.

The tunnel complex described in Figure 10 (labeled the final plan) is in the shape of a “U” with two tunnel entrances. This plan can be exactly correlated with commercial satellite imagery (see Figure 12 and Annex 5, where the plans are superimposed on a 2004 Google Earth image of the site). In particular, there is a perfect alignment to the ventilation shaft (HVAC), where the HVAC heat exchanger unit (square unit) is visible on the satellite imagery.

The hybrid plan in Figure 9 shows a shorter tunnel complex than in the one in Figure 10 but has the same names for the half-buried rooms as in Figure 8. This plat of half-buried structures can be almost exactly overlain on the area outside the tunnel, including a notch that had been dug into an adjacent hillside after construction started on this project (see Figure 13 and Annex 5).24 It could be that the plan in Figure 9 is focused only on the half-buried rooms and simply omitted the part of the underground tunnel facility that leads from underneath the mountain to the second tunnel entrance. Alternatively, it could be that the design of the facility was changed and all the rooms intended to be half-buried were shifted to inside the tunnel. The tunnel complex is large enough to hold all the rooms described in Figure 8. In any case, based on evaluating commercial satellite imagery post-2004, the half-buried portion of the site described in Figure 9 was not built (see Figure 14).

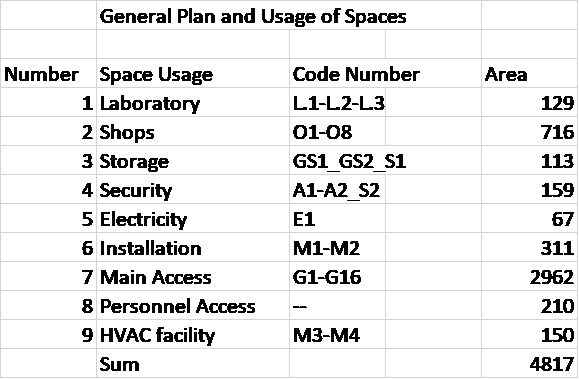

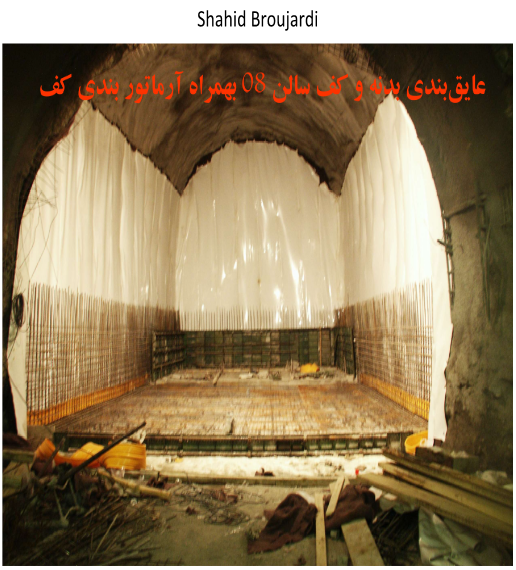

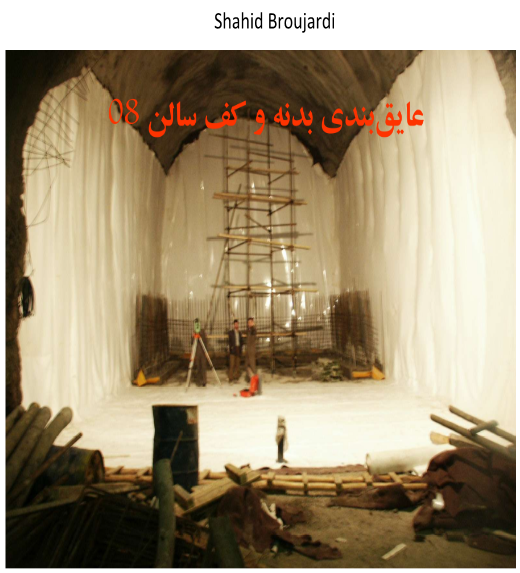

Another Farsi document, an annotated plat, with a title of “Coding Plan Legend,” and a table titled “General Plan and Usage of Space,” provides floor areas and code names of the halls inside the tunnel, at least in a general manner, such as security, shops, laboratories, HVAC facilities, and tunnel sections, and locates these rooms in the tunnel complex under the fully buried plan. The coding appears related to the room’s function in English, e.g. E1 is electricity or electrical. The appearance of this plat after the plats in figure 9 and 10 adds some weight to the notion that the facility shifted to rooms that were only fully buried. The plat itself is difficult to read but is included in Figure 15 which also has a translation of its legend. Figure 16 shows the location of key areas on the plat shown in Figure 10 of the fully buried facility. Figure 17 shows one of the shops, marked O8, under construction.

Figure 16 shows that one area of the tunnel complex has a series of rooms within a noticeably secure area. This area is behind at least three dedicated security rooms or areas, one each located along the tunnel access routes, and a third in the cross tunnel connecting these two routes just prior to the rooms designated by “M.” These rooms include the shops O1, O2, O3, O4, O5, and O6 and the three laboratories, with a code of L1, L2, and L3. With these characteristics, these shops, where “O” could stand for operation, could be where the reduction, melting, casting, and machining of uranium metal were to take place. Moreover, any uranium handling was likely planned to be done under hoods with exhaust systems, or possibly even in some cases in glove boxes, to extract any uranium particles in the air, making proximity to the HVAC facility a potential advantage.

Rooms M1 and M2, labelled “installation rooms,” are visible in Figure 16. It is unclear what is the function of an installation room, but they might reasonably be involved in mechanical or possibly metallurgical processing operations.

The facility with fully buried rooms has a total floor area of about 4817 square meters (see Figure 15). Subtracting the main and personnel access routes leaves a total of 1,645 square meters of floor space. Three laboratories have floor areas of 129 square meters, and eight shops have 716 square meters. Combined, the laboratories and shops have a floor area of 845 square meters. This floor area is similar to the area of shops and laboratories in the hybrid plan of fully and half-buried rooms given in the table in Figure 8, which is 805 square meters. Both also have the same total number of laboratories and shops, namely eleven. The table in Figures 9 and 11 gives a somewhat larger floor space for the half-buried rooms.

The installation rooms have a floor area of 311 square meters. Adding installation rooms to that of the laboratories and shops increases their combined area to 1,156 square meters. Storage, security, electricity, and HVAC facility require 489 square meters, bringing the total to 1645 square meters.

Overall, this site’s location and layout would connotate a production-scale facility rather than a research and development facility. The archive documents available to the Institute do not provide any information on the exact equipment procured for this site or the site’s expected annual output. However, one cover sheet of this project in the archive lists the goal of producing 50 kilograms, according to Israeli briefers.25 However, the cover sheet does not state explicitly whether the 50 kilograms refers to the annual production of weapon-grade uranium. Nonetheless, it can be extrapolated (with a high degree of uncertainty) that this is the annual goal quantity of weapon-grade uranium in finished components. Although the uncertainty has to be emphasized, this throughput would roughly match the expected annual weapon-grade uranium output of the Al Ghadir project; later renamed by Iran the Fordow enrichment plant after its discovery by Western intelligence, and re-purposed to low enriched uranium production (to be further assessed in a forthcoming Institute report). Assuming 15-20 kilograms of weapon-grade uranium per weapon, this facility could produce enough weapon-grade uranium components for an average of 2.5-3.3 nuclear weapons per year.

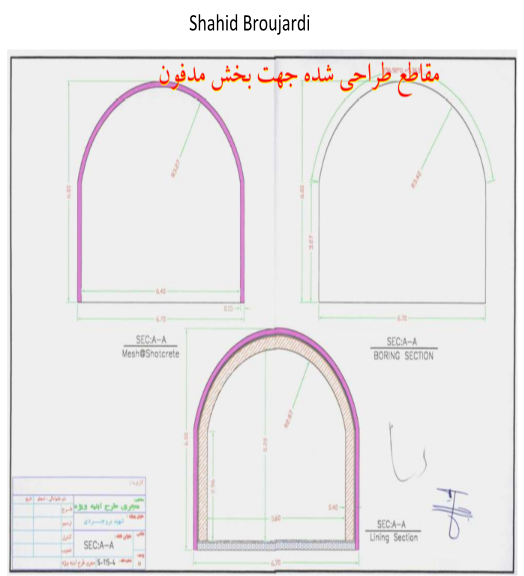

Tunnel Construction

Tunnel construction was well underway by early 2003. Figure 18 shows a design or cross section of the buried section, showing Shahid Boroujerdi’s planned three phases of tunnel construction—boring, mesh (reinforcement), and concrete lining. The design has two signatures in the lower right corner that match those on the contract (see Annex 2), meaning that Sayed Shamsuddin Borborudi of the Institute for Training and Research of Defense Industries (ITRDI) of Iran’s Defense Ministry and Mr. Amir Hajizadeh of NAHSA signed this design drawing.

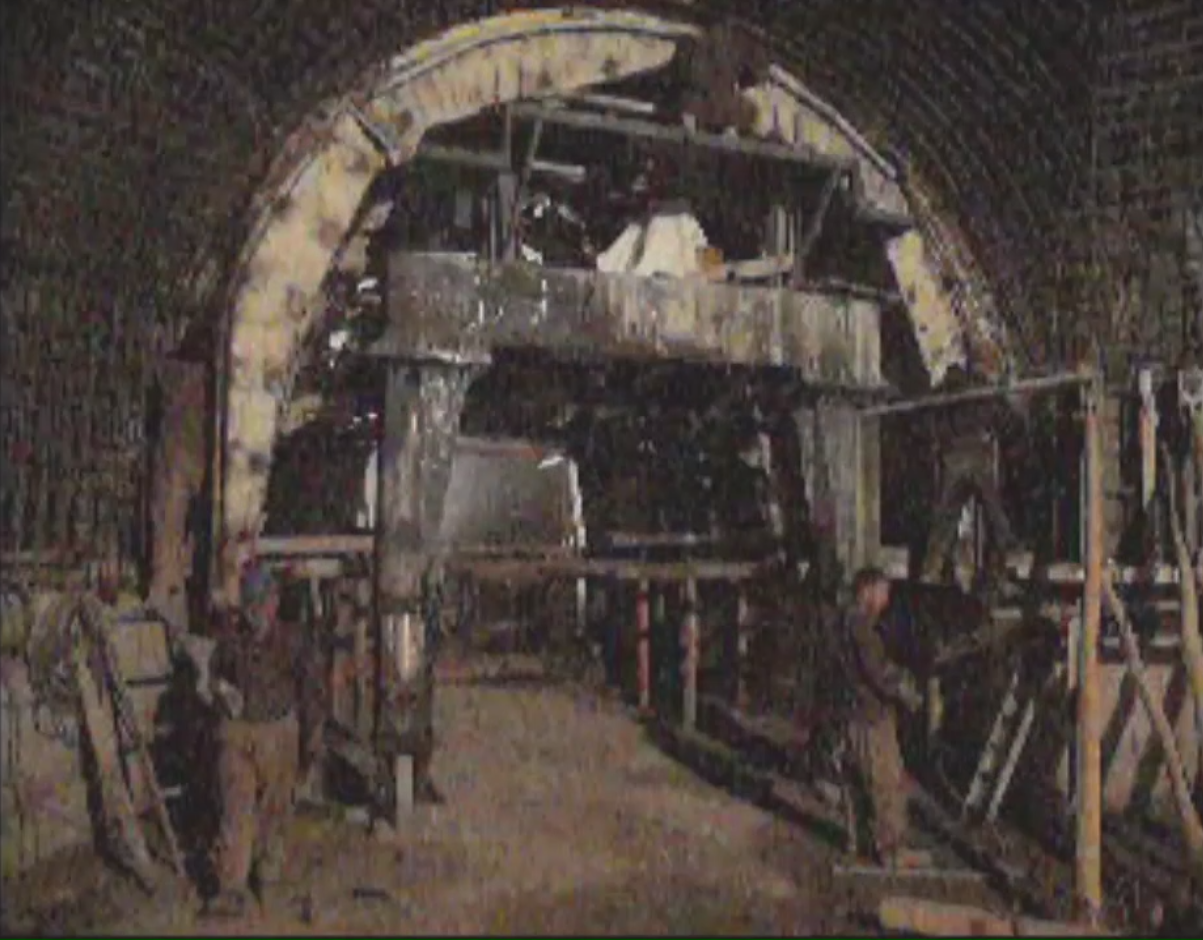

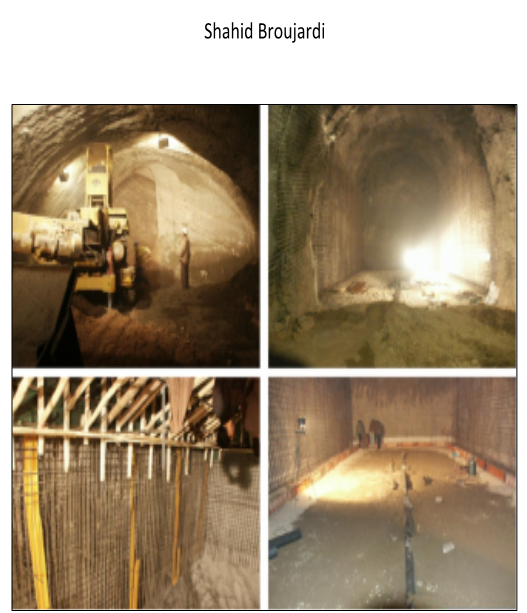

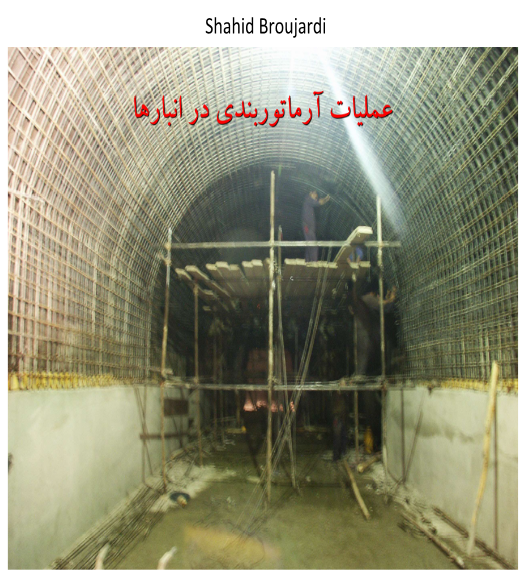

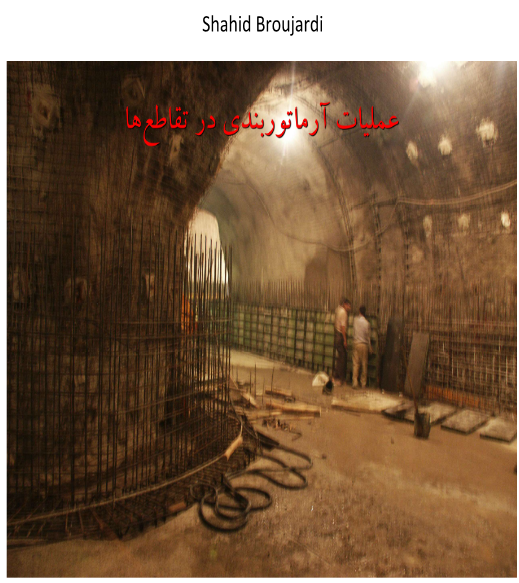

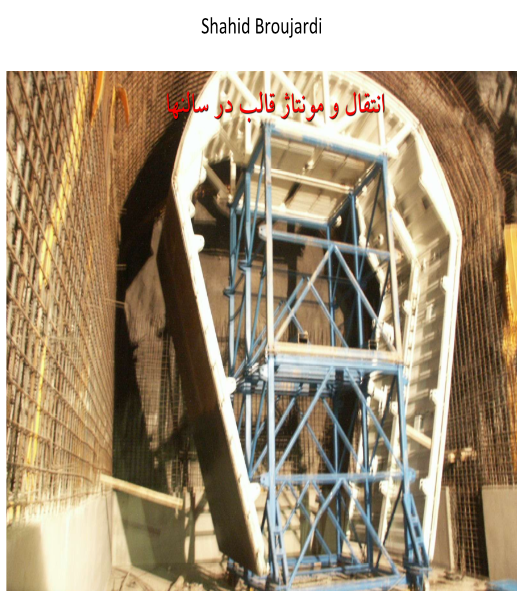

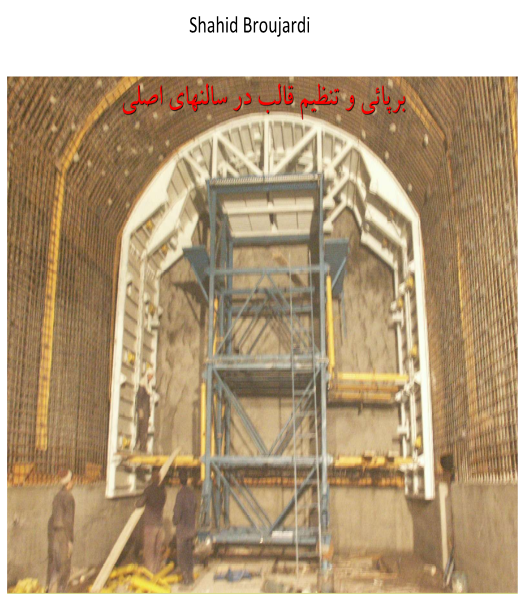

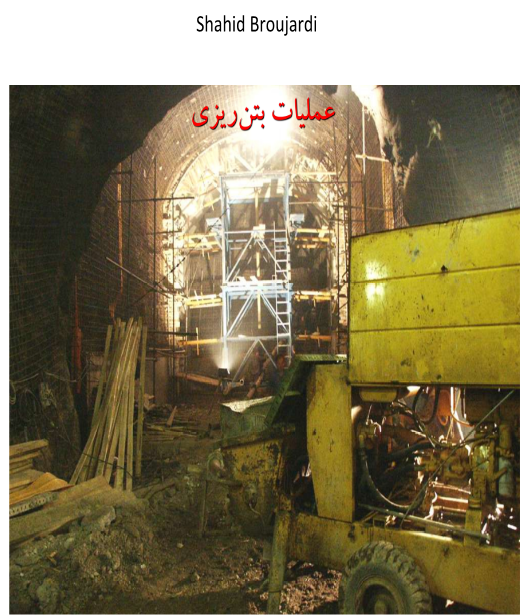

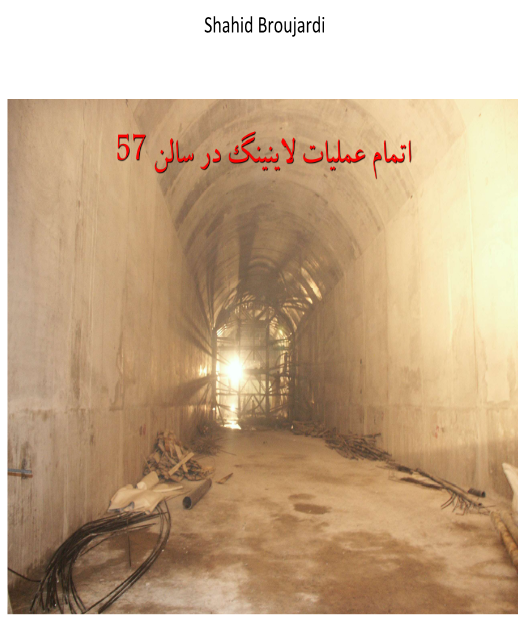

According to the Iranian documents, namely the section titled “Ending of Excavation,” the boring or excavation work on the tunnel was completed on March 25, 2003. Lining of the tunnel started earlier on March 2, 2003. Figure 19 shows two photographs of the tunnel and hall construction process, and the estimated location of these images in the tunnel system. Figure 20 shows from the Shahid Boroujerdi collection a tunnel excavator and a composite of images of different stages of construction of a room inside the tunnel. Figure 21 shows reinforcement operations in the tunnel and the erection of a specialized frame in a room. Figure 22 shows concreting of the tunnel and a tunnel section after the concrete lining operation was completed.

The documents do not contain information on the completion of the facility. The project was delayed from its original expected completion date of May 20, 2003 but it was making steady progress by that date.

According to Israel, construction of the Shahid Boroujerdi project, namely to make uranium metal components of nuclear weapons, stopped before equipment was installed.26 Moreover, as discussed above, the portion of the facility outside the tunnel entrance was not built.

The site has never been inspected, according to the reports by the IAEA, and Iran is not known to have discussed this site with the IAEA. Who controls this site or its purpose today is not known. However, it can be seen in commercial satellite imagery (see Figure 14) that this site did eventually become operational, and therefore, warrants further scrutiny.

What did the IAEA know prior to the seizure of the Nuclear Archive?

This particular tunnel complex at Parchin was identified many years ago, however, its purpose was not clear at the time. A nuclear use was not ascribed to it.

Senior Israeli intelligence officials stated in a briefing of one of the authors on November 1, 2018 that this site was known, but not its purpose as a facility under the Amad Plan.27 The IAEA also did not know about this facility being part of Amad.

A major gap in the information available to the IAEA has concerned uranium metallurgy relevant to making nuclear weapons, and Iran has consistently denied having ever pursued any such activities. According to the 2015 IAEA final report on the possible military dimensions to Iran’s nuclear program, “Iran informed the [IAEA] that it had not conducted metallurgical work specifically designed for nuclear devices, and was not willing to discuss any similar activities that did not have such an application.”28

Up until the seizure of the archive, the IAEA had a limited amount of information suggesting that Iran was developing a capability to produce uranium metal for nuclear weapons. According to the 2015 report:

The information also indicated that preliminary activities, including the ‘green salt project’, were undertaken at an unknown location and were aimed at the production of uranium salts that would have been suitable either for conversion into material for uranium enrichment or into material for the direct reduction of uranium salts to pure uranium metal. This information stemmed from the alleged studies documentation and other information, from Member States, and indicated that these activities ceased when the AMAD Plan was brought to a halt in late 2003. The information indicated that the work involved was not at an advanced stage. The information indicated that preliminary work aimed at implementing this process involved the use of surrogate materials to avoid the possibility of uncontrolled contamination. Other information indicated that Iran was developing, outside its declared nuclear fuel cycle, processes for the reduction of uranium salts to pure uranium metal. Information contained in the alleged studies documentation links the uranium salts to be produced with warhead development.29

The IAEA has not stated that it possessed prior to the archive seizure any information suggesting the construction of a production-scale facility under the Amad plan at this site, or to produce uranium metal and form uranium components from the resulting metal at such a site.

Nonetheless, according to the information accumulated by the IAEA, Iran’s quest for uranium metal production capabilities goes back to before the Amad program. Although the IAEA was not able to locate where Iran worked on developing and producing uranium metal components for nuclear weapons, it did accumulate a variety of information that suggested that Iran was pursuing efforts to master the production and casting of enriched uranium metal for use in nuclear weapons.

In 1987, when Iran was revitalizing its uranium enrichment program, it received, in addition to an offer from intermediaries for a 2000-machine centrifuge enrichment plant, an offer to provide necessary technologies and equipment related to uranium reconversion from uranium hexafluoride to metal and casting capabilities.30 In January 2005, Iran acknowledged to the IAEA receiving these offers and presented to the inspectors a one-page, handwritten document reflecting the receipt of these offers. Iran stated to the IAEA that the AEOI had not requested uranium processing capabilities, which appear to have been meant to produce uranium metal, and Iran claimed the AEOI had not received this offer.

However, the AEOI proceeded soon after to acquire from foreign sources uranium conversion technologies, which led later to the construction of the Uranium Conversion Facility (UCF) in Esfahan. UCF has process lines to produce not only uranium hexafluoride feed material for uranium enrichment, but also a variety of other uranium compounds, including uranium metal.31 Parallel to the design and construction of the UCF, Iran embarked on intensive R&D to produce, inter alia, uranium hexafluoride and uranium metal. These activities were conducted in secret using imported nuclear and source materials without fulfilling Iran’s reporting obligations under the comprehensive safeguards agreement.32

When the above mentioned activities were revealed by the IAEA, Iran agreed in October 2003 to take corrective actions and provide a full declaration on its past nuclear activities.33 However, Iran failed to include at that time in its declaration to the IAEA the 1996 acquisition of more advanced, P-2 type centrifuges.34 The IAEA investigations revealed indications that the provision of technology in 1996 by foreign entities likely included also uranium conversion technologies. As a response to the IAEA requests and other findings, Iran provided the IAEA in November 2007 with a 15-page document describing the procedures for the reduction of uranium hexafluoride to uranium metal and the machining of highly enriched uranium metal into hemispheres, which are components of nuclear weapons.35 Iran maintained that this document had been part of the P-1 centrifuge documentation obtained in 1987 from abroad and that it had not been requested by Iran. Interviews of Iranian and other officials and intermediaries involved in the procurement of technologies in 1996 also indicated the involvement of persons other than AEOI officials in negotiations and handling of these documents.

The current information points to a turning point in Iran’s nuclear weapons program in the time period of 1996-1999. This included the receipt of a document on making uranium-based nuclear weapon components, and soon afterwards, recruiting foreign expertise on nuclear weapon design,36 the establishment of the Supreme Council for Advanced Technologies,37 and the launching of the Amad plan, including the Shahid Boroujerdi project.38 There are also indications that companies close to the military establishment were attempting to acquire dual-use equipment suitable for uranium metal work. This shift in the program was led by a new group of leaders. Gholam Reza Aghazadeh became head of the AEOI in 1997, and Mohsen Fakhrizadeh took the helm of the military nuclear program at about the same time.

Final Word and Recommendations

The Institute has carried out detailed assessments of secret nuclear weapons programs throughout the world since its founding in 1992. As such, and not surprisingly, the Institute decided to seek out and independently assess the information in the Nuclear Archive soon after Prime Minister Netanyahu revealed the archive in April 2018. The authors decided to form an informal technical group, whose members have decades of experience in the nuclear areas in the archive. Israel distributed some of this information to journalists, which the Institute acquired from them. In addition, Israel provided some members of this group, due to their competence and past work on this topic, a deeper look at the material in the archives. Over the last three months alone, we have conducted over a half dozen studies of the information in the Nuclear Archive. The work is continuing. It is now apparent that the archive is extremely rich in information about Iran’s nuclear weapons efforts that is actionable in terms of better carrying out inspections, judging Iran’s prior incomplete and duplicitous statements about its nuclear programs, and more adequately understanding the threat that program poses today and in the future.

The archive contains considerable new information about Iran’s nuclear weapons effort and brings into much sharper focus both the strengths and weaknesses of the IAEA’s information about Iran’s nuclear weapons efforts, not only in the past, but also today. In particular, the new information shows the insufficiency of the IAEA’s previous efforts to address this effort, largely summarized (incorrectly) as issues associated with the Possible Military Dimensions (PMD) of Iran’s nuclear program. Moreover, storing and curating an extensive nuclear weapons archive could be construed as not having abandoned the goal of seeking nuclear weapons. The new information raises fundamental questions about whether Iran is complying with its comprehensive safeguards agreement, the Additional Protocol, the JCPOA, and more broadly, with the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. It is difficult to excuse the IAEA’s hesitancy to address this new information about the Amad project as provided in the captured portion of the archive.

The IAEA Board should urge IAEA to verify sites, locations, facilities, and materials involved in these activities, and Iran to cooperate fully in these investigations. Time is of the essence. Information available from the archives has been available close to one year, which has given Iran an opportunity to conceal any ongoing activities, which it has done in the past.

The provisions of the JCPOA, with the current IAEA monitoring regime, would not be able to detect and precipitate action in time to block Iran from dashing to a nuclear weapon within a short period of time, particularly as restrictions on enrichment start to end beginning in five years. If such weapons-related capabilities are not removed or rendered harmless, the probability increases that countries will decide to block Iran via military means. Non-action also increases the probability that other states in the region will build their own independent military nuclear capabilities using loopholes in the NPT regime and, if necessary, concealment. The United States and parties to the JCPOA should work now to prevent a renewed Iranian nuclear crisis, before time runs out.

Figure 1. Cover sheet of a document from the Iranian archive for Project Shahid Boroujerdi, original in Farsi and translation.

Figure 2. The upper image is a commercial satellite image showing the location of the Shahid Boroujerdi project at the Parchin military armaments complex and the relative location of the High Explosives Test Chamber site which was also part of the Amad nuclear weapons effort (see http://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/new-information-about-the-parchin-site/8). The lower images, from a 2004 Institute study, identify the site but its purpose could not be ascertained at the time. It was not suspected to have been a nuclear facility. Senior Israeli intelligence officials stated that they had no information prior to the seizure of the archive that this tunnel site at Parchin was connected to the Amad effort.

Figure 3. Chart from the Iranian archive showing more detail about Project Shahid Boroujerdi, original in Farsi and translation.

Figure 4. Chart from the Iranian Nuclear Archive showing Shahid Boroujerdi Project details, original in Farsi and translation. The date of the chart is after April 30, 2002 but likely before May 30, 2003.

Figure 5. Ground photos from the Iranian archive. The one on the upper left, dated April 25, 2002, shows the movement of equipment to the Shahid Boroujerdi tunnel site. The bottom right image, dated May 4, 2002, shows an outline drawn on the photo showing the general area of tunneling beyond the first tunnel entrance area (see Annex 3).

Figure 6. The top left image is from the Iranian archive that shows a tunnel excavator in the open outside the first tunnel entrance. A frontal image of this excavator, also called a roadheader, is in the top right image from the archive. This excavator appears to match closely with a long, narrow vehicle in the commercial satellite image of the Parchin tunnel entrance area. The vehicles appear to match in their physical proportions, their position and orientation vis-a-vis the back-cut wall, as well as their shadows (the photos were taken almost the same time of day in the same general time of year in 2002). Moreover, these two photos were definitely taken at the same location, as the ground photo shows multiple stepped terracing along the back-wall and one step on the left side-wall, exactly as can be found on the Google Earth satellite image.

Figure 7. Upper image is a frame-grab of a video in the archive shown by Prime Minister Netanyahu on April 30, 2018, purporting to show an underground facility to produce “nuclear cores,” which means uranium metal components of a nuclear weapon. The lower image is from the Shahid Boroujerdi documents with the title “framing in an access route.” The framing equipment is similar to that in the one above. The lower image appears to show a portion of the tunnel at an earlier stage of construction.

Attachment 4

Physical Program

Description of the beneficiary’s intended spaces based on the past correspondence, the negotiations of the meeting dated October 7, 2002 [Translator’s note: or May 5, 2002 (but unlikely)], and the option selected by the honorable management of project 110 is as follows

Figure 8. Room Functions, translated table, Farsi original in Annex 4.

Figure 9. The Design Plan in a Hybrid Manner (Half-Buried and Buried), also dated November 12, 2002. The table and text in the bottom right quadrant of the plan are translated in Figure 11.

Figure 10. A plan or plat titled, Project’s Final Plan in a Fully Buried Manner, and dated November 12, 2002. The signature in the lower right part of the plan matches one of those on the contract, meaning that Sayed Shamsuddin Borborudi of the Institute for Training and Research of Defense Industries (ITRDI) of Iran’s Defense Ministry or Mr. Amir Hajizadeh of NAHSA signed this design drawing.

Figure 11. Translation of right hand, bottom quadrant of half-buried plan in Figure 10.

Authors’ Note: The total area in the nine spaces or rooms in the table adds to 983 square meters, which is less than the total area of the Buildings, given as 1293 meters squared. The areas of routes appear to be in the half-buried sections. It should also be noted that the total area of the half-buried rooms in this figure differs somewhat from the area of these half-buried rooms given in the table in Figure 8. More floor space is allocated in this plat.

Figure 12. An overlay of the fully buried plan, Figure 9, overlain on a 2004 Google Earth image of the site. Two tunnel entrances and a HVAC unit align perfectly (see also Annex 5).

Figure 13. Upper image is a 2004 Google Earth image of the main tunnel entrance. Lower image is same Google Earth image with plan for half-buried rooms from Figure 9 overlain.

Figure 14. Google Earth image from September 26, 2018 showing that the half-buried rooms were not built in the original open alcoves. The underground tunnel complex appears to have been subsequently repurposed with the construction of an open bay building at the primary tunnel entrance. A newer alcove (further removed from the entrance) was also excavated for a building that appears to be for the purpose of supplying various utility services to the redeveloped underground complex. The repurposed site appears to now be operational for an as yet unidentified military application. Given its previous nuclear weapons fabrication association subordinate to the Amad Project, the tunnel complex should be investigated to ensure that it no longer is involved in any undeclared nuclear related activities.

Figure 15. Plat titled “Coding Plan Legend, plus translation of the key on the plat, organized with only fully buried rooms and providing space usage, code names, and floor areas. The code numbers G1-G16 correspond to sections of the tunnel and comprise most of the area of the facility. The total area of the rooms, minus G1-G16 areas, is 1855 square meters.

Figure 16. Fully buried plat with rooms and areas identified as in Figure 15, superimposed on a March 2004 Google Earth image.

Figure 17. Hall or shop O8 under construction. Caption of upper image reads: Insulation of walls and floor of hall O8 and reinforcement of the floor. Caption of bottom image reads: Insulation of walls and floor of hall O8. Hall O8 is the top most shop in Figure 16. Its exact function is not described in the documents.

Figure 18. Cross-sections of the buried section of the tunnel showing various phases of construction. The signatures in the lower right corner match those on the contract (see Annex 2), meaning that Sayed Shamsuddin Borborudi of the Institute for Training and Research of Defense Industries (ITRDI) of Iran’s Defense Ministry and Mr. Amir Hajizadeh of NAHSA signed this design drawing.

Figure 20. On left, a composite of images from the archive of different stages of construction of a room inside the tunnel. On right, also from archive, a roadheader or tunnel excavating tool, called a Paurat in Farsi. Paurat was a German construction equipment manufacturer that is no longer in business.

Figure 21. From the archives, the top images show reinforcement operation in a storage room and at an intersection. The bottom images show the placement and erection of a frame in a main room or hall.

Figure 22. Construction images from the Shahid Boroujerdi project. The left image shows the concreting operation. The right image is a section of the tunnel that shows the end of the concrete lining operation in hall 57.

1. Olli Heinonen is Former Deputy Director General of the IAEA and head of its Department of Safeguards. He is a Senior Advisor on Science and Nonproliferation at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies.

2. Frank Pabian is a retired Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) Fellow from both the Global Security and Science-Technology-Engineering Directorates, most recently in the Geophysics Group, Earth and Environmental Sciences Division, with 45 years of experience in satellite remote sensing for nuclear nonproliferation. He also served in the 1990s as a United Nations Nuclear Chief Inspector in Iraq for the IAEA. * The authors wish to thank Behnam Ben Taleblu of FDD for his consultations on this paper. We also wish to thank Linda Keenan for her assistance during our translation sessions.

3. Documentation seized from Tehran contains, according to Israeli statements, some 55,000 pages and another 55,000 files on 183 CDs. Israeli officials estimated that this represented about 20 percent of the material stored at the archive. See: Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Presentation, April 30, 2018, Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qmSao-j7Xr4↩

4. Some of the information is still to be fully vetted.↩

5. For more on the nature, time period, and evolution of the Amad program, see David Albright, Olli Heinonen, and Andrea Stricker, “Breaking Up and Reorienting Iran’s Nuclear Weapons Program: Iran’s Nuclear Archive Shows the 2003 Restructuring of its Nuclear Weapons Program, then called the AMAD Program, into Covert and Overt Parts,” Institute for Science and International Security, October 29, 2018, http://isis-online.org/isis-reports/mobile/breaking-up-and-reorienting-irans-nuclear-weapons-program↩

6. IAEA Director General, Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement and relevant provisions of Security Council resolutions in the Islamic Republic of Iran (see Annex), GOV/2011/63, November 8, 2011, https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/gov2011-65.pdf↩

7. The ITRDI is responsible for high technology and science in the Ministry of Defense. It organizes education and research for the development of technology and the modernization of Iran’s defense industries. It is also known as Defense Industries Training and Research Institute or Training and Research Institute of Defense Industries. NAHSA is also known as the Aerospace Force of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. It is sometimes abbreviated as NHSA.↩

8. In previous publications, we have capitalized AMAD; in this report we have started to use Amad, since the Farsi word means logistics, particularly related to military logistics. The Farsi word, as best as we can determine, is not an acronym.↩

9. The IAEA has often referenced the “Amad Plan.” In several documents in the Nuclear Archive, the Iranians refer to the “Amad Supraorganizational Plan.” Here, we use both nomenclatures, as well as Amad project or program.↩

10. Briefing in Tel Aviv of Albright by senior Israeli officials, November 1, 2018.↩

11. The documents state 14/3 but our translator also stated that this could be read as 3/14. Equivalently, these can be read as 14.3 or 3.14 since a forward slash in Farsi is a decimal point in English.↩

12. Project 110 had four main sections, according to a chart in the Nuclear Archive—Warhead Project, Nuclear Test Site Project, Operating System Project, and Simulation Project. Each project had a code number associated with it. The Operational System Project had code number 30. Code 36 could be a subproject of the Operational System Project.↩

13. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohammad_Boroujerdi. Other spellings of his name exist. We are using a common one in English.↩

14. See also David Albright, Olli Heinonen, and Andrea Stricker, “The Plan: Iran’s Nuclear Archive Shows it Originally Planned to Build Five Nuclear Weapons by mid-2003,” Institute for Science and International Security/Foundation for Defense of Democracies, November 20, 2018, http://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/the-plan-irans-nuclear-archive-shows-it-originally-planned-to-build-five-nu/8↩

15. IAEA Director General, Final Assessment on Past and Present Outstanding Issues regarding Iran’s Nuclear Programme, GOV/2015/68, December 2, 2015, https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/gov-2015-68.pdf↩

16. lbright, Heinonen, and Stricker, “Breaking Up and Reorienting Iran’s Nuclear Weapons Program.” This study used only the first pages of this archive document. It is much longer and contains detailed discussions about continuing the various aspects of Iran’s nuclear weapons program, sensitive technical information, and cover stories on activities and procurements. Israel did not declassify and/or release this study in its entirety because of these details.↩

17. It is unknown what is the fate of the technology, including all of the project’s designs, the equipment associated with producing, melting, casting, and finishing uranium metal parts, and any nuclear or other key materials associated with this facility.↩

18. Ali Alfoneh, “The Revolutionary Guard’s Business Empire,” AEIdeas, American Enterprise Institute, May 13, 2010, http://www.aei.org/publication/the-revolutionary-guards-business-empire/ ; and Ali Alfoneh, “How Intertwined Are the Revolutionary Guards in Iran’s Economy?” Critical Threats, October 22, 2007, https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/how-intertwined-are-the-revolutionary-guards-in-irans-economy↩

19. F. may stand for the Farsi word for headquarters.↩

20. In Persian, the decimal point or separator is called momayyez and is written like a forward slash.↩

21. Briefing in Tel Aviv of Albright by senior Israeli officials, November 1, 2018.↩

22. The date could have been May 5, 2002, although the translator believed that the date was most likely October 7, 2002.↩

23. David Albright, Paul Brannan, and Andrea Stricker, The Physics Research Center and Iran’s Parallel Military Nuclear Program, Institute for Science and International Security, February 23, 2012, http://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/PHRC_report_23February2012.pdf↩

24. The only apparent mis-match is that the angle of the cut for the one alcove appears a bit shallower in the drawing that it was in reality. This slight difference may have been due to a minor engineering design change.↩

25. Briefing of Albright, November 1, 2018.↩

26. Ibid.↩

27. Ibid.↩

28. IAEA Director General, Final Assessment on the Past and Present Outstanding Issues Regarding Iran’s Nuclear Programme, GOV/2015/68, December 2, 2015, http://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/IAEA_PMD_Assessment_2Dec2015.pdf↩

29. Ibid.↩

30. IAEA Director General, Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement in the Islamic Republic of Iran, GOV/2005/67, September 2, 2005, https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/gov2005-67.pdf↩

31. IAEA Director General, Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement in the Islamic Republic of Iran, Para 25, GOV/2010/10, February 18, 2010, https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/gov2010-10.pdf↩

32. IAEA Director General, Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement in the Islamic Republic of Iran, GOV/2003/75, November 10, 2003, https://www.iaea.org/ sites/default/files/gov2003-75.pdf↩

33. Ibid, Para 13.↩

34. IAEA Director General, Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement in the Islamic Republic of Iran, Para 44, GOV/2004/11, February 24, 2004, https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/gov2004-11.pdf↩

35. IAEA Director General, Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement in the Islamic Republic of Iran, Para 19, GOV/2008/14, February 22, 2008, https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/gov2008-4.pdf↩

36. IAEA Director General, Final Assessment on Past and Present Outstanding Issues regarding Iran’s Nuclear Programme, Para 43, GOV/2015/68, December 2, 2015, https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/gov-2015-68.pdf↩

37. David Albright, Olli Heinonen, and Andrea Stricker, “The Plan: Iran’s Nuclear Archive Shows It Planned to Build Five Nuclear Weapons by mid-2003,” Institute for Science and International Security/Foundation for Defense of Democracies, November 20, 2018, http://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/The_Plan_Iran_Archive_20Nov2018_Final.pdf<a href=”#ref37” title=”Jump back to footnote

twitter

twitter