Peddling Peril Index

Signs of Responsible Statecraft Are Missing in Most Signatories of the Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty

by David Albright, Sarah Burkhard, and Spencer Faragasso

April 7, 2022

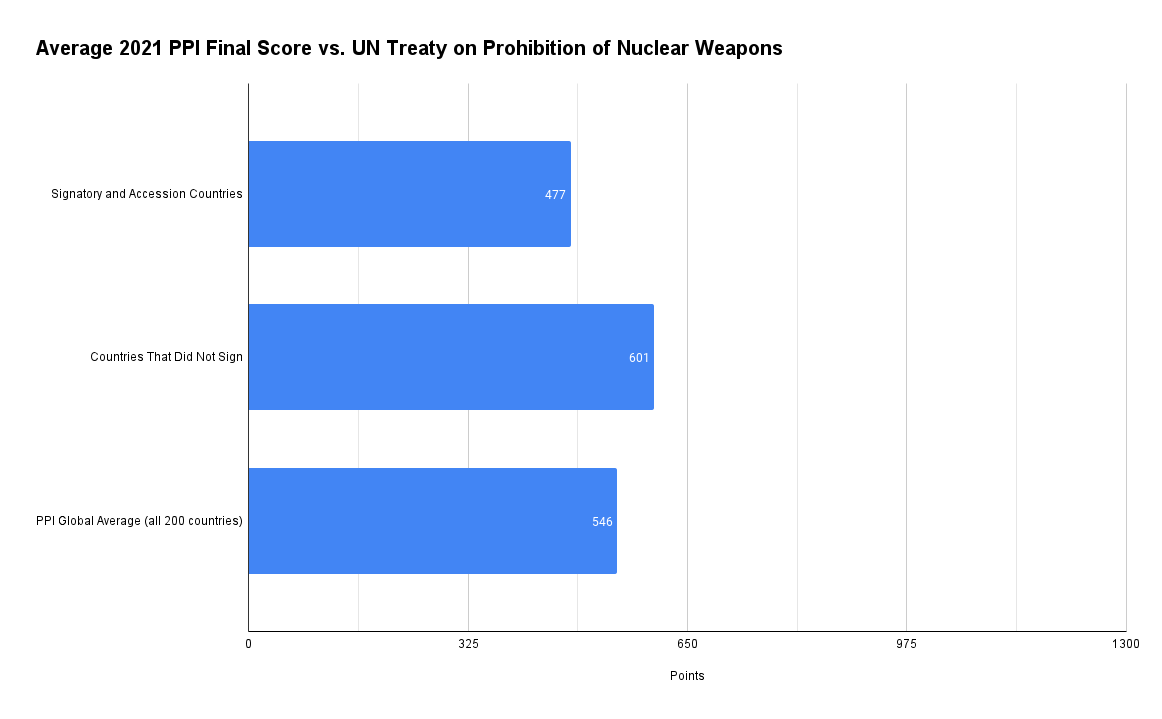

The Institute found a general lack of responsible state actions among the 89 countries that have signed or acceded to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty, or TPNW) to date, compared to those countries that have abstained from signing it. This finding flows from data compiled in the Peddling Peril Index (PPI) for 2021/2022. The PPI is a measure of both the effectiveness of national strategic trade controls and adherence to widely accepted and long-standing international treaties and conventions, making it a useful indicator for responsible state actions overall in addition to its traditional role in ranking 200 countries’ and entities’ strategic trade controls. The correlation with the PPI identified a concerning lack of demonstrated commitment and implementation of international arms control, trade control, and financial practices among the current 89 signatory and accession countries of the Ban Treaty. The majority of countries (some 64 percent, or 57 out of 89) that have signed or acceded to the Ban Treaty rank in the bottom half of the PPI ranking, and 29 percent, or 26 countries, rank in the bottom quarter. These 89 countries scored an average of 477 points in the PPI, or just over one-third of the possible points. This is below the global average for all 200 countries and entities considered in the PPI, which lies at 546 points. The Ban Treaty appears to be signed mostly by countries with little commitment to existing international norms, treaties and conventions, or to implementing strategic trade and financial controls, all fundamental international tools to stop the spread of nuclear weapons and slow the growth of nuclear arsenals.

The preamble language of the treaty may further open the door to those states seeking to undermine other countries’ strategic trade controls, an action inconsistent with the goals of U.N. Security Council Resolution 1540 (2004) mandating UN members to have national strategic trade controls, a resolution directly linked to stopping the spread of nuclear weapons.

The data show most of these countries lack adequate export control legislation to serve as a firm basis to control the trade in nuclear and nuclear-related dual-use commodities that are critical to the production and possession of nuclear weapons. If the Ban Treaty signatories truly seek a world without nuclear weapons, they should take the lead in ensuring that all countries, including their own, act responsibly, adhere to international law and long-standing non-proliferation norms and treaties, and have effective, implemented strategic trade control systems, capable of preventing the spread of dangerous and critical commodities and facilities involved in the production, maintenance, and improvement of nuclear weapons.

Background

On July 7, 2017, a United Nations conference charged with negotiating a treaty prohibiting nuclear weapons voted in Geneva to accept a sparse, ten-page document with grand ambitions to ban nuclear weapons worldwide.1 At the conference, 122 countries voted in favor of accepting the treaty. Not a single country currently possessing nuclear weapons voted to support the Ban Treaty (see Sidebar). Furthermore, the Netherlands, the only NATO member involved in the negotiations, voted against the treaty at the conference.2 The treaty opened for signature on September 20, 2017, but despite the 122 countries voting in favor of it, it took more than three years, until January 2021, to achieve 50 ratifications and enter into force. As of March 23, 2022, 89 countries have signed or acceded to the treaty (with 57 ratifications and three accessions, for a total of 60 parties). Thirty-seven countries did not sign the treaty despite their initial support, for a total of 104 (out of 193) UN members that have not signed.

At the time of the vote in 2017, the Institute considered the 122 countries in favor of the treaty according to their export control legislation as evaluated under the Peddling Peril Index for 2017/2018.3 The findings revealed that the majority of countries (about 76 percent, or 93 out of 122) did not have adequate export control legislation. Several of the countries had also fought against strengthening the nuclear non-proliferation aspects of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) at NPT Review Conferences and were against strongly implementing UN Resolution 1540, including its mandate to implement national trade control systems.

This report updates the correlation between the Peddling Peril Index and the Ban Treaty proponents, using the latest edition of the PPI and including only those countries that have since signed or acceded to the Ban Treaty. It further deepens the analysis by incorporating additional subsets of data from the PPI, such as countries’ implementation of widely accepted non-proliferation norms, treaties and conventions, adherence to international trading practices, implementation of financial controls, and governments’ responsible enforcement practices.

The preamble of the Ban Treaty contains a statement, seemingly innocuous on the surface, but actually a setback for efforts to stop or slow nuclear weapons proliferation through the implementation of strategic trade controls. The preambular language, “Emphasiz[es] that nothing in this Treaty shall be interpreted as affecting the inalienable right of its States Parties to develop research, production and use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes without discrimination.”4 This phrase has historically been at the heart of the argument used by countries such as Iran that there exists a global right to free nuclear trade that export controls contradict. By implication, therefore, for many of these countries, regimes controlling nuclear supply should not exist or should not apply to them. Their position is inherently counter to the efforts of many countries that seek to stop the spread of dangerous nuclear and nuclear-related commodities and the unauthorized export or transshipment of goods or facilities associated with nuclear reactors, plutonium reprocessing, uranium enrichment, and nuclear weaponization, because they see this proliferation as unduly increasing the risk that more countries will acquire nuclear weapons.

The widespread lack of adequate export controls would make the verification of nuclear disarmament difficult, if not impossible, in a post-nuclear weapons world. While the Ban Treaty is strict on verifying a state’s elimination of nuclear weapons, the treaty is silent on how verification would work once most, or all states gave up their nuclear weapons. In a post-nuclear weapons world, individual countries would be highly incentivized to seek nuclear weapons in secret, a challenge significantly worsened by lack of effective trade controls.

The Peddling Peril Index

The Peddling Peril Index assesses the commitment and ability of countries worldwide to support nonproliferation and strategic trade control measures. The PPI ranks 200 countries using 105 different sub-criteria across five overarching Super Criteria: International Commitment, Legislation, Ability to Monitor and Detect Strategic Trade, Proliferation Financing, and Adequacy of Enforcement. While most sub-criteria are point-earning criteria, points can also be deducted from countries when negative information is available, such as having high levels of corruption, or being involved in documented evasions of international sanctions on North Korea. A final score out of a maximum 1300 possible points is calculated for each country, and the evaluated countries are ranked by their score.

The PPI Super Criterion International Commitment measures countries’ membership and adherence to international nonproliferation treaties and conventions; Legislation judges the regulatory environment and legal status that exists within a state to support strategic trade control measures; Ability to Monitor and Detect Strategic Trade assesses a state’s capabilities and practices that enable them to control strategic trade; Ability to Prevent Proliferation Financing measures a state’s capability to prevent the financing of WMD proliferation-related activities; and Adequacy of Enforcement measures how well a country employs enforcement activities against strategic commodity trafficking and sanctions evasion.

In general, countries that achieve higher scores in the PPI show a greater ability, commitment, and willingness to support and implement strategic trade controls, nonproliferation measures, and related international norms and treaties.

Correlation of Ban Treaty Signature with PPI Average Scores

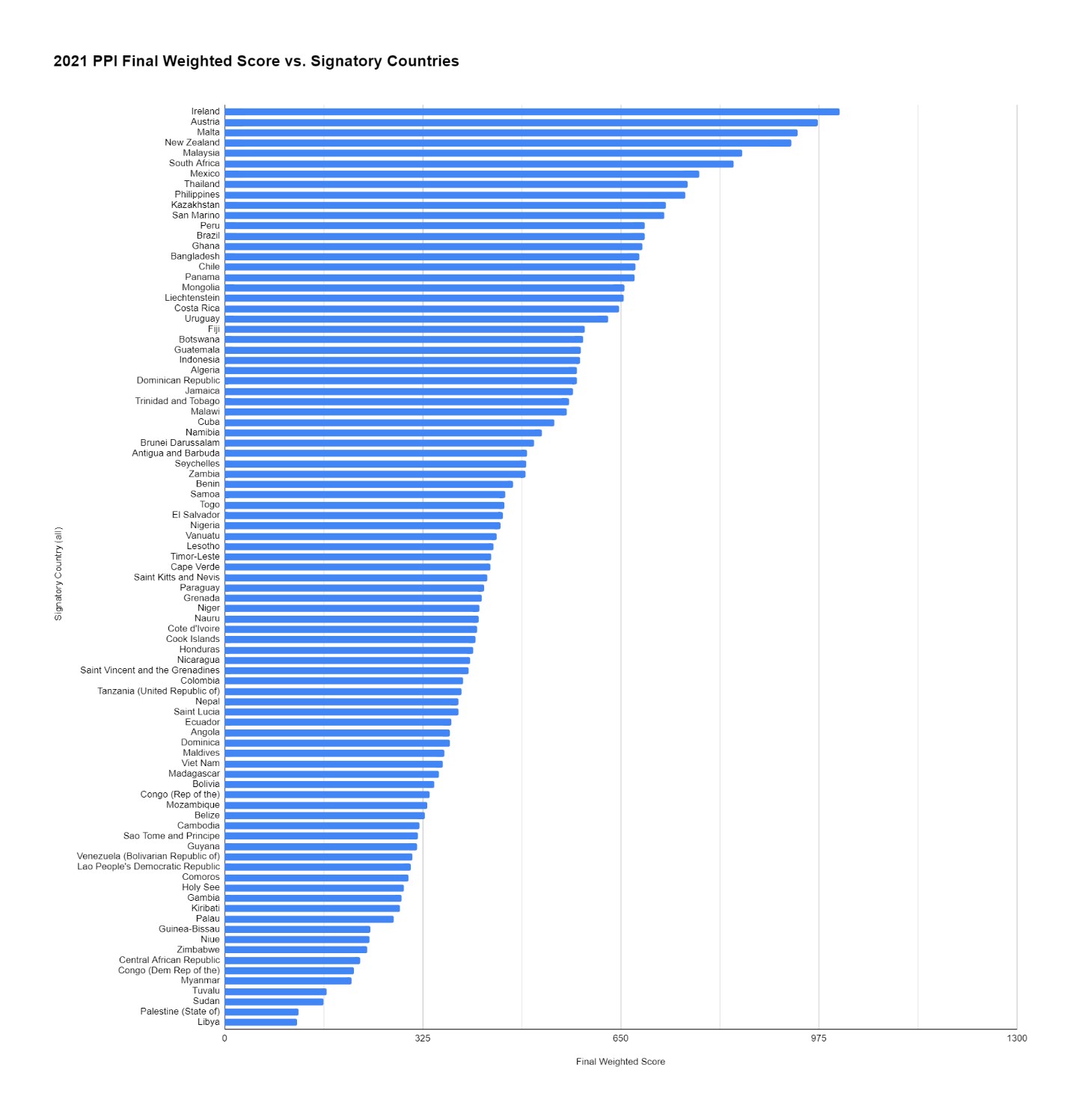

The majority of countries (some 64 percent, or 57 out of 89) that have signed or acceded to the Ban Treaty rank in the bottom half of the PPI ranking, and 29 percent, or 26 countries, rank in the bottom quarter. In order of highest to lowest PPI score, these are the countries that signed or acceded to the treaty:

Ireland, Austria, Malta, New Zealand, Malaysia, South Africa, Mexico, Thailand, Philippines, Kazakhstan, San Marino, Peru, Brazil, Ghana, Bangladesh, Chile, Panama, Mongolia, Liechtenstein, Costa Rica, Uruguay, Fiji, Botswana, Guatemala, Indonesia, Algeria, Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, Malawi, Cuba, Namibia, Brunei Darussalam, Antigua and Barbuda, Seychelles, Zambia, Benin, Samoa, Togo, El Salvador, Nigeria, Vanuatu, Lesotho, Timor-Leste, Cape Verde, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Paraguay, Grenada, Niger, Nauru, Côte d’Ivoire, Cook Islands, Honduras, Nicaragua, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Colombia, Tanzania (United Republic of), Nepal, Saint Lucia, Ecuador, Angola, Dominica, Maldives, Viet Nam, Madagascar, Bolivia, Congo (Rep of the), Mozambique, Belize, Cambodia, Sao Tome and Principe, Guyana, Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of), Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Comoros, Holy See, Gambia, Kiribati, Palau, Guinea-Bissau, Niue, Zimbabwe, Central African Republic, Congo (Dem Rep of the), Myanmar, Tuvalu, Sudan, Palestine (State of), and Libya

The 89 countries scored an average of 477 points in the PPI, or just over one-third of the 1300 possible points. This is below the global average for all 200 countries considered in the PPI, which lies at 546 points (see Figure 1). Figure 2 shows that 19 countries scored above half of the possible points (650 points), while 20 scored below one-quarter (325 points). With respect to the five super criteria in the PPI, in International Commitment, this group achieved 50 points on average (out of 100 possible points), in Legislation 100 (out of 200), Ability to Monitor and Detect Strategic Trade 92 (out of 200), Ability to Prevent Proliferation Financing 87 (out of 400), and Adequacy of Enforcement 147 (out of 400). In all five super criteria, the group received fewer points than the global PPI average.

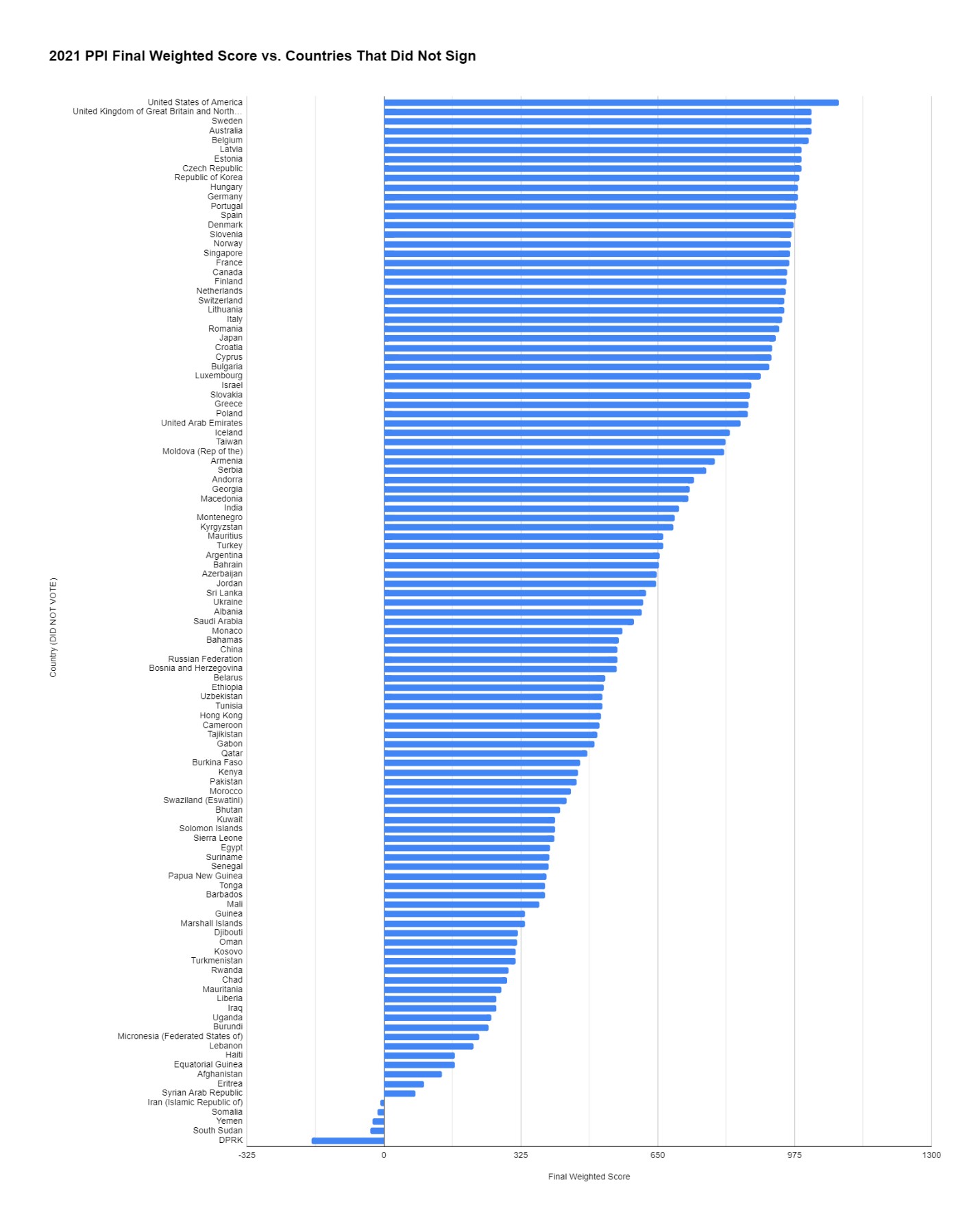

The group of 111 countries evaluated in the PPI that did not sign or accede to the treaty had higher average scores both overall and across all five PPI super criteria than the global PPI average, and considerably higher scores than the group of countries that has signed or acceded to the treaty. Figure 3 shows the overall scores for these countries, where 50 countries scored above half of the possible points. Certainly, there are also countries in this group that did not sign or accede to the Ban Treaty and scored poorly in the PPI, such as countries that currently do have nuclear weapons, for example Pakistan and North Korea. Nevertheless, this group of countries has an average score of 600 points in the overall PPI: 58 points in International Commitment, 141 points in Legislation, 111 points in Ability to Monitor and Detect Strategic Trade, 112 points in Preventing Proliferation Financing, and 178 points under Enforcement. The score difference between countries that have and have not signed or acceded to the Ban Treaty is largest under Legislation.

Figure 1. This bar graph compares the average PPI score of countries that have signed or acceded to the Ban Treaty, countries that have not signed the treaty, and the global average in the PPI for all 200 countries.

Figure 2. The final weighted PPI score for all countries that signed or acceded to the Ban Treaty.

Figure 3. The final weighted PPI score for all PPI countries that did not sign or accede to the treaty.

Correlation of Ban Treaty Signature with PPI Data on Export Control Legislation

As part of the research for the Legislation super criterion in the PPI, the Institute analyzed export control legislation of 200 nations or territories. Our findings placed countries and territories into five categories regarding the quality and extensiveness of a country’s export control legislation relating to nuclear and nuclear-related dual use goods. Ideally, national export control legislation references a comprehensive list of controlled items, such as Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) Parts I and II lists.

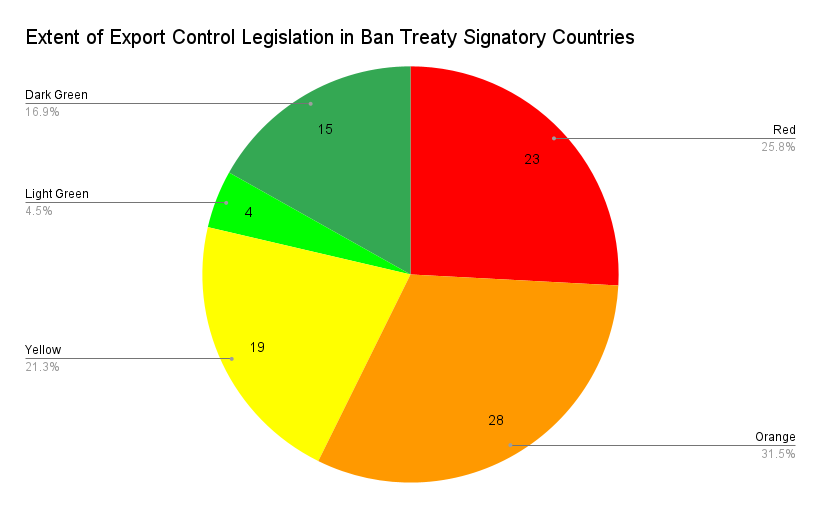

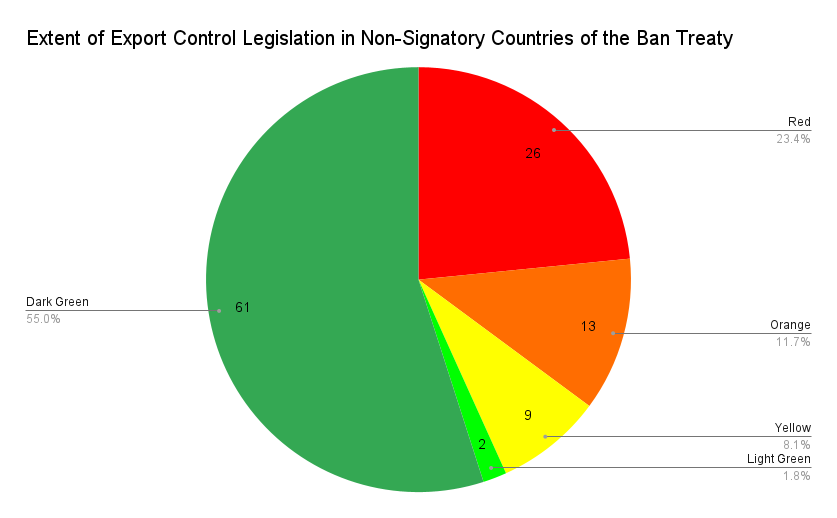

Countries that signed or acceded to (shortened to “signed” below) the Ban Treaty were categorized into the five levels of comprehensiveness of their export control legislation as established by the PPI. The categories are Red, Orange, Yellow, Light Green, and Dark Green, where Red signifies that legislation is nonexistent, Light and Dark Green are considered adequate, and Orange and Yellow are levels in between.

The findings include:

Red: 23 of the countries that signed the Ban Treaty as of March 2022. Their export controls may include small arms and light weapons (SALW), and/or radioactive materials under environmental laws. These are not considered relevant export control legislation for the PPI.

Orange: 28 of the countries that signed the Ban Treaty. Export control legislation or agreements include only conventional weapons as laid out under the Arms Trade Treaty. These are not considered relevant export control legislation for the PPI.

Yellow: 19 of the countries that signed the Ban Treaty. These countries have comprehensive, overarching nuclear safety and security laws that place transfer controls on nuclear material and equipment. If we were unable to locate the relevant legislation, the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI) Nuclear Security Index was consulted, specifically its data on whether a country has or does not have a national legal framework for the Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material (CPPNM). These countries are not viewed as having effective export control laws governing nuclear and nuclear-related commodities, but their existing legislation is viewed as better in a relevant export control sense than the legislation or lack of legislation in the red and orange categories.

Light Green: 4 of the countries that signed the Ban Treaty. Export control legislation or agreements includes controls or clauses relating to nuclear direct-use goods (i.e., nuclear commodity controls such as implementation of Nuclear Suppliers Group Part I list or an equivalent), and conventional weapons.

Dark Green: 15 countries that signed the Ban Treaty. Export control legislation or agreements includes controls or clauses relating to nuclear direct-use and nuclear dual-use goods, (i.e., nuclear and nuclear-dual use commodity controls such as implementation of NSG Parts I & II or their equivalent).

Comparing the levels of export control legislation of the 89 countries that signed or acceded to the Ban Treaty and the remaining 111 countries evaluated in the PPI that did not, only 21 percent (or 19 countries) of these 89 countries have adequate export control legislation, compared to 57 percent (or 63 countries) of those that did not sign or accede to the Ban Treaty it (see Figures 4 and 5).

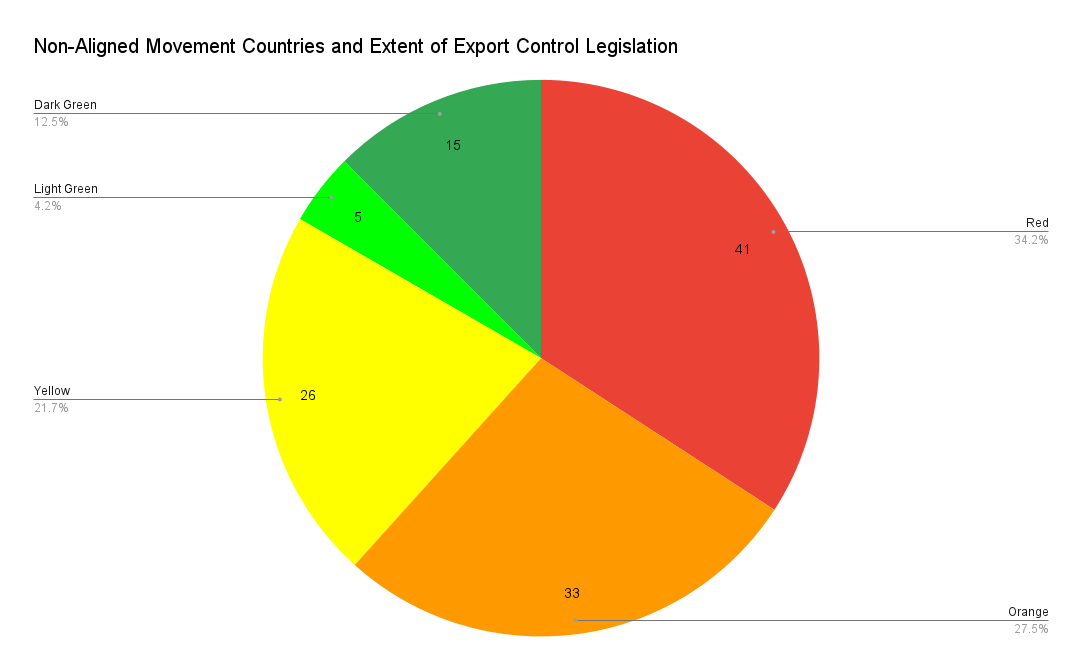

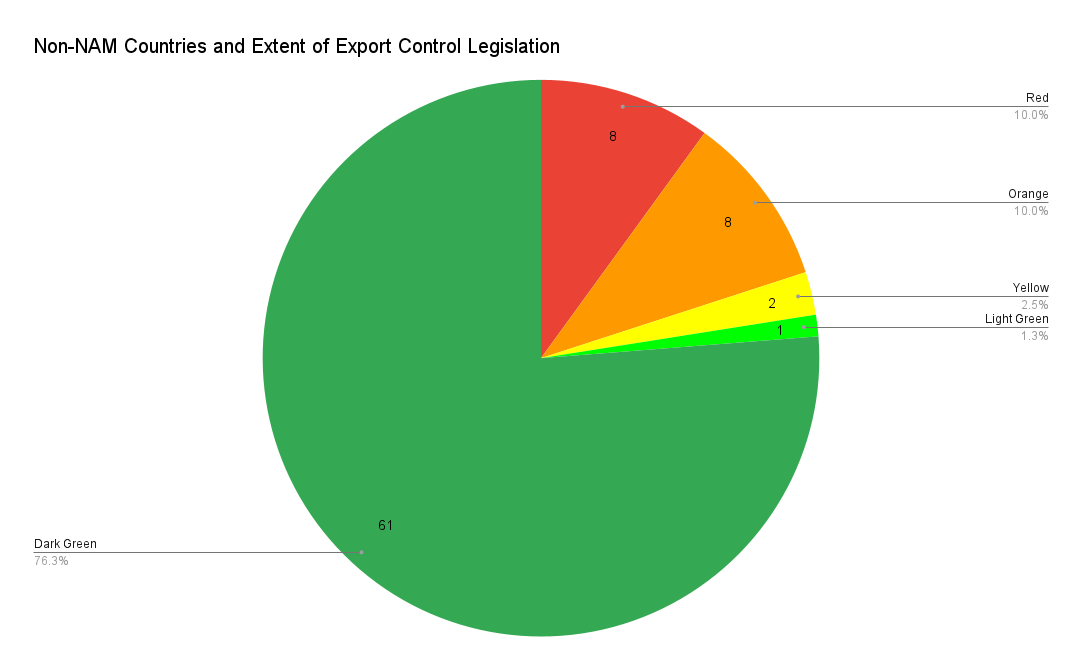

Sixty-eight countries that signed or acceded to the Ban Treaty are also members of the NAM. Of these 68 countries, only 10 have adequate export control legislation. In contrast, of the 59 countries that are not in the NAM and did not sign or accede to the treaty, 53 have adequate export control legislation. These results follow a general trend. Of all 120 countries that belong to NAM, only 17 percent (20 countries) have adequate export control legislation compared to 78 percent (62 of 80 countries) that do not belong to the NAM (see Figures 6 and 7).

Figure 4. The vast majority of countries that signed or acceded to the Ban Treaty have inadequate export control legislation (yellow, orange, or red color categories) as evaluated in the 2021 PPI.

Figure 5. Comprehensive export control legislation (green categories) is more common in countries that did not sign or accede to the Ban Treaty.

Figure 6. Over 80 percent of the countries in the Non-Aligned Movement lack adequate export control legislation.

Figure 7. In stark contrast, 78 percent of countries that are not part of the Non-Aligned Movement do have comprehensive export control legislation.

1. UN News Centre, “UN Member States Set to Adopt ‘Historic Treaty Prohibiting Nuclear Weapons,” July 6, 2017, http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=57131#.WbqeG8iGMdV. ↩

2. Peter D. Zimmerman, “This New U.N. Treaty Seeks to Ban Nuclear Weapons. But We’d Regret it if We Did,” The Washington Post, September 14, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/posteverything/wp/2017/09/14/the-u-n-s-new-treaty-banning-nuclear-weapons-sounds-like-a-good-idea-its-not/?utm_term=.ec37f5b8659e. ↩

3. David Albright, Sarah Burkhard, Allison Lach, and Andrea Stricker, “Most Nuclear Ban Treaty Proponents are Lagging in Implementing Sound Export Control Legislation,” Institute for Science and International Security, September 27, 2017, https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/most-nuclear-ban-treaty-proponents-are-lagging-in-implementing-sound-export/. ↩

4. United Nations General Assembly, Draft Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, July 6, 2017, http://undocs.org/A/CONF.229/2017/L.3/Rev.1. ↩

5. P5 Joint Statement on the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, October 24, 2022, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/p5-joint-statement-on-the-treaty-on-the-non-proliferation-of-nuclear-weapons. ↩

6. David Albright with Sarah Burkhard and the Good ISIS Team, Iran’s Perilous Pursuit of Nuclear Weapons (Washington, DC: Institute for Science and International Security Press, 2021). ↩

7. Iran’s Perilous Pursuit of Nuclear Weapons. ↩

8. Algeria, Argentina, Australia, Belarus, Brazil, Canada, China, DPRK, Egypt, France, Germany, India, Iran (Islamic Republic of), Iraq, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kazakhstan, Libya, Norway, Pakistan, Republic of Korea, Romania, Russian Federation, Serbia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Syrian Arab Republic, Taiwan, Ukraine, United Kingdom, and United States of America. ↩

twitter

twitter