Reports

Analysis of IAEA Iran Verification and Monitoring Report - September 2023

by David Albright, Sarah Burkhard, Spencer Faragasso, and Andrea Stricker

September 8, 2023

Background

● This report summarizes and assesses information in the International Atomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA’s) quarterly report, dated September 4, 2023, Verification and monitoring in the Islamic Republic of Iran in light of United Nations Security Council resolution 2231 (2015), including Iran’s compliance with the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). It also covers findings from a separate IAEA report, NPT Safeguards Agreement with the Islamic Republic of Iran, issued also on September 4, 2023.

Findings

● Iran retains the ability, using 40 kilograms (kg) of 60 percent highly enriched uranium (HEU) and three or four advanced centrifuge cascades, to break out and produce enough weapon-grade enriched uranium for a nuclear weapon in 12 days. Currently, Iran would only need one-third of its existing stock of 60 percent enriched uranium. This breakout could be difficult for the IAEA to detect promptly, if Iran delayed inspectors’ access.

● Using more of its remaining stock of 60 percent enriched uranium in the same three or four cascades, and its stock of near 20 percent enriched uranium in the vast bulk of its production-scale cascades, Iran could produce enough weapon-grade uranium (WGU) for an additional five nuclear weapons within the first month of a breakout, bringing the total to enough WGU for six nuclear weapons, or an increase of one since May 2023. Thus, Iran has increased its breakout capability, despite only a small increase in its 60 percent stock (see below), because its near 20 percent and less than five percent LEU stocks increased.

● In the second month, using its remaining stock of 60 percent material and part of its stock of less than 5 percent low enriched uranium (LEU), Iran could produce enough WGU for an additional two weapons. Using the rest of its stock of less than 5 percent LEU) (but greater than 2 percent enriched uranium), Iran could produce enough WGU for a ninth weapon by the end of the third month, and a tenth by the end of the fourth month.

● In summary, Iran could produce enough WGU for six nuclear weapons in one month, eight in two months, nine in three months, and ten in four months. Iran’s stockpile of 60 percent HEU was 121.6 kg (Uranium mass, or U mass) or 179.9 kg uranium hexafluoride mass (hex mass) as of August 19.

● The amount of 60 percent HEU produced during this most recent reporting period was about half of the amount produced during the previous reporting period, despite comparable timespans. The average production rate dropped from 9 kg (U mass) per month to 4.3 kg.

● The IAEA reports that from mid-June onwards, Iran reduced the production rate of near 60 percent HEU “by approximately two-thirds,” indicating that during this reporting period, which spans mid-May to mid-August, one month at full production was followed by two months of reduced production.

● Of note, Iran only recently doubled its production of near 60 percent HEU when it started, in November 2022, to enrich to near 60 percent HEU in two advanced centrifuge cascades at Fordow. Thus, for six months, from December 2022 to June 2023, it accumulated about double the monthly average amount compared to the previous year and may still be able to hit an annual production target even if it were to stop producing 60 percent altogether for the next six months.

● The IAEA also reports that Iran downblended 6.4 kg (Uranium mass) of its near 60 percent stock by mixing it with near 5 percent LEU to produce 22.2 kg of 20 percent enriched uranium. Because it was not downblended to natural uranium or to at least near 5 percent LEU, the downblending had little impact on the breakout timelines.

● Overall, neither the slow-down in 60 percent production nor the downblending improved the breakout situation; in fact, the situation worsened.

● Iran continued to produce 60 percent HEU from 5 percent LEU feed in advanced centrifuge cascades at the above-ground Pilot Fuel Enrichment Plant (PFEP) and the below-ground Fordow Fuel Enrichment Plant (FFEP); the latter includes an IR-6 centrifuge cascade that is easily modifiable to change operations. This cascade was at the center of an IAEA-detected undeclared mode of operation in January 2023. It was interconnected with another IR-6 cascade to produce HEU, and subsequently, the IAEA detected the presence of near-84 percent HEU particles at the cascade’s product sampling point.

● The IAEA has “accepted Iran’s explanation for the origin of these particles” and verified that no diversion of declared uranium and no accumulation of uranium enriched to more than 60 percent took place. At the same time, the IAEA sought increased access and intensification of verification activities at the FFEP. In a May 2023 report on Iran’s compliance with the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), the IAEA reported that it installed enrichment monitoring devices (EMD) at both the FFEP and at the PFEP to “monitor the enrichment level of the HEU being produced by Iran.” These monitors are not JCPOA-related but are installed pursuant to Iran’s comprehensive safeguards agreement (CSA) with the agency. IAEA Director General Rafael Grossi confirmed in a press conference that the EMD data will notify the IAEA of “another oscillation or otherwise” in the enrichment level in “real-time.” The IAEA reports, “The evaluation of the data collected confirmed the general good functioning of the systems.” However, “adjustments and changes to operational procedures required to enable their commissioning […] are being discussed with Iran.”

● Iran continues to keep the majority (83 percent) of its stock of 60 percent HEU and nearly 85 percent of its stock of 20 percent enriched uranium at the Esfahan Fuel Plate Fabrication Plant (FPFP), where Iran maintains a capability to make enriched uranium metal. Iran’s storage of so much proliferation-sensitive material at the FPFP, which may not be as thoroughly monitored as Natanz and Fordow, requires enhanced IAEA safeguards to detect and prevent diversion to a secret enrichment plant. For example, there should be stepped up inspector presence and remote camera surveillance.

● As of August 19, 2023, Iran had an IAEA-estimated stock of 535.8 kg of 20 percent enriched uranium (U mass and in the form of UF6), equivalent to 792.6 kg (hex mass), representing an increase of 64.9 kg from 470.9 kg (U mass). Iran also had a stock of 33 kg (U mass) of 20 percent uranium in other chemical forms.

● The average production rate of 20 percent enriched uranium at the FFEP increased slightly to 13.2 kg (U mass) or 19.6 kg (hex mass) per month.

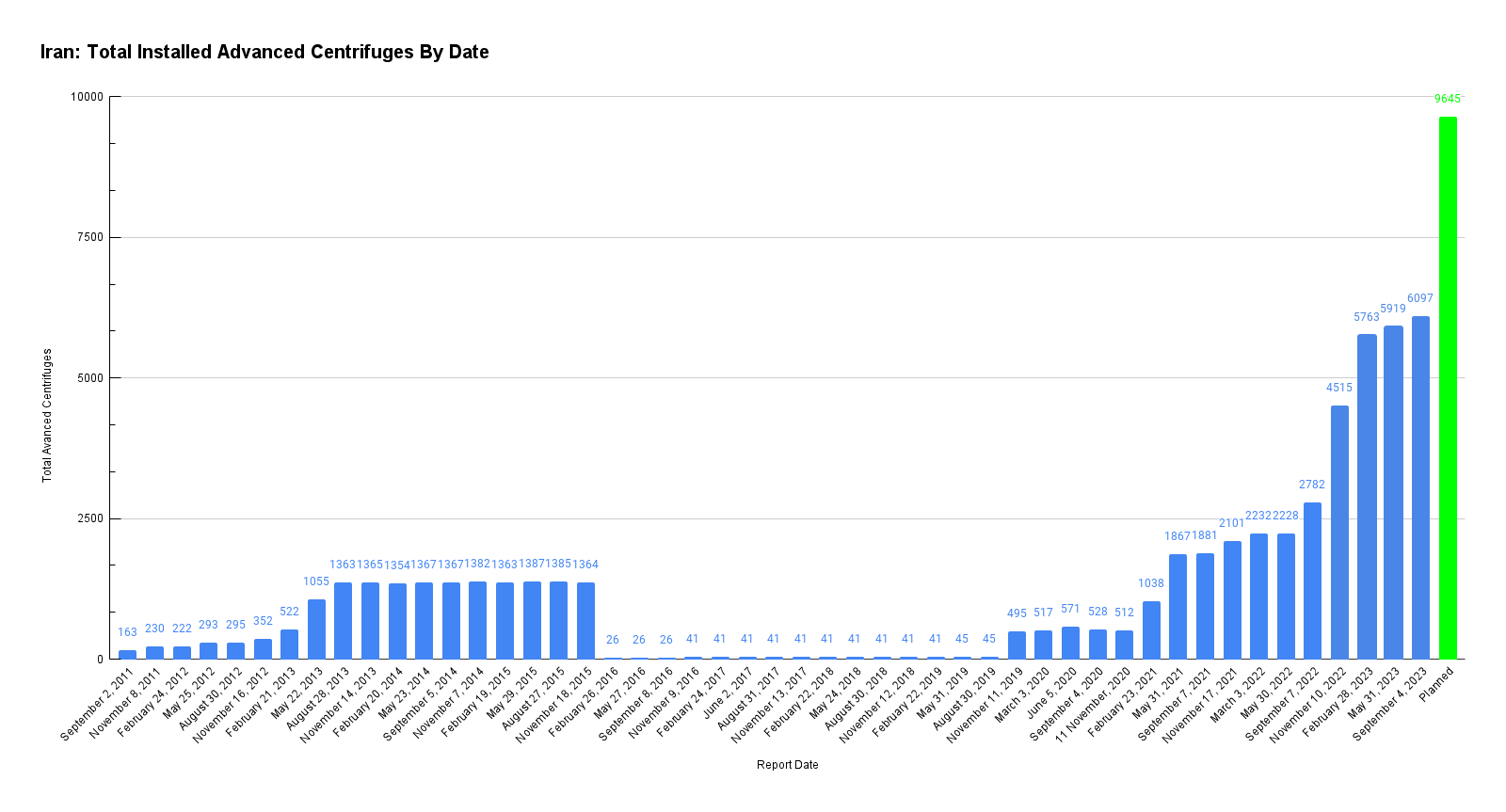

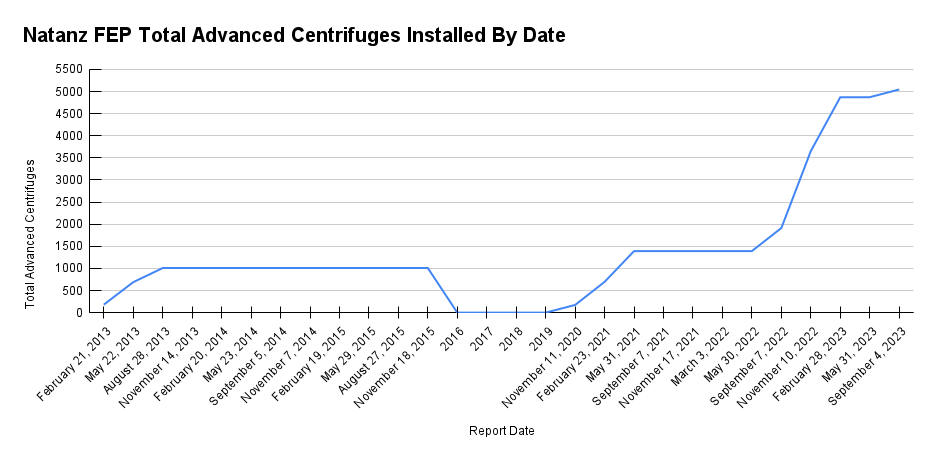

● Iran’s number of installed advanced centrifuges has remained fairly steady since February 2023. It now has a total of about 6100 advanced centrifuges at Natanz and Fordow, where most are deployed at the Natanz Fuel Enrichment Plant (FEP) (see Figures 1 and 2).

● Including the installed IR-1 centrifuges at Natanz and Fordow brings the total number of installed centrifuges to about 13,330 centrifuges. It should be noted that many of the advanced centrifuges are deployed but not enriching uranium, and the IR-1 centrifuges have far less ability to enrich uranium than the advanced ones.

● During this reporting period, Iran installed one additional cascade of IR-4 centrifuges at the Natanz Fuel Enrichment Plant (FEP), where Iran now has a total of 36 cascades of IR-1 centrifuges, 21 cascades of IR-2m centrifuges, five cascades of IR-4 centrifuges, and three cascades of IR-6 centrifuges installed. An additional seven IR-4 centrifuge cascades are planned, and the installation of one IR-4 cascade was ongoing.

● Iran did not install any additional advanced centrifuge cascades at the FFEP, where it is currently operating six IR-1 centrifuge cascades and two IR-6 centrifuge cascades, although it plans to install up to 14 additional IR-6 centrifuge cascades.

● This lull in deployment was preceded by a spike in advanced centrifuge deployment from August 2022 to February 2023. A slowing of advanced centrifuge deployments and enrichment using those machines may be one reported term of an informal nuclear understanding with the United States, although this is unverified. It is unclear whether this means Iran is produced fewer centrifuges than expected, implying possible manufacturing difficulties, or is keeping newly produced machines in unmonitored storage instead.

● Iran’s current, total operating enrichment capability is estimated to remain at about 19,100 separative work units (SWU) per year, where only cascades enriching uranium during this reporting period are included in this estimate. As of this reporting period, Iran was not yet using its fully installed enrichment capacity at the FEP.

● Iran’s overall reported stockpile of enriched uranium decreased by 949 kg (U mass) from 4744.5 kg to 3795.5 kg (U mass) (see Table 1). This decrease largely stems from a decrease in uranium enriched to less than 2 percent, while all other stocks grew.

● Iran’s stockpile of near 5 percent LEU increased by 610.7 kg (U mass) to 1950.9 kg (U mass) or 2885.9 kg (hex mass). Average production of near 5 percent LEU at the FEP increased, while the feed rate for 20 percent and 60 percent enriched uranium production decreased.

● Despite the increase during this reporting period in the amount of uranium enriched between two and five percent, Iran has not prioritized stockpiling this material over the past two and a half years. In addition, it has not made planned progress on the Enriched Uranium Powder Plant, a key civil facility to convert less than five percent enriched uranium hexafluoride into a uranium oxide powder for use in nuclear power reactor fuel. These two choices are at odds with Iran’s contention that its primary goal is to accumulate 4-5 percent enriched uranium for use in nuclear power reactor fuel. Instead, Iran has used this stock extensively to produce near 20 percent and 60 percent enriched uranium, far beyond Iran’s civilian needs.

● The IAEA reported no progress by Iran on resolving a discrepancy in Iran’s natural uranium inventory at the Uranium Conversion Facility (UCF). The IAEA previously reported a shortfall in Iran’s declaration, which may indicate that Iran mixed into the UCF inventory undeclared uranium it used in the past at the Lavisan-Shian site during its early-2000s nuclear weapons program. After acknowledging a discrepancy, Iran insisted that the discrepancy is “inaccurate” and “baseless,” and that “differences” are “predictable” and that “the matter is considered as resolved.” The IAEA did not agree with Iran’s claim.

● The IAEA reports that Iran has not started commissioning the Arak reactor, now called the Khondab Heavy Water Research Reactor (KHRR), or IR-20. Iran previously informed the IAEA that it expected to commission the reactor in 2023 and start operations in 2024, but construction efforts on the reactor continue.

● The IAEA underscores that “for more than two and a half years Iran has not provided updated declarations and the Agency has not been able to conduct any complementary access under the Additional Protocol to any sites and locations in Iran.”

● The IAEA reports no new progress on installing new surveillance cameras at Iran’s nuclear-related facilities, including centrifuge manufacturing and assembly sites. Iran also has not turned over data or footage associated with monitoring devices and cameras, as it committed in an IAEA/Iran Joint Statement from March 2023.

● The absence of monitoring and surveillance equipment, particularly since June 2022, has caused the IAEA to doubt its ability to ascertain whether Iran has diverted or may divert advanced centrifuges. A risk is that Iran could accumulate a secret stock of advanced centrifuges, deployable in the future at a clandestine enrichment plant or during a breakout at declared sites. Another risk is that Iran will establish additional centrifuge manufacturing sites unknown to the IAEA. Iran has proven its ability to move manufacturing equipment to new, undeclared sites, further complicating any future verification effort and contributing to uncertainty about where Iran manufactures centrifuges.

● Iran’s refusal to implement the non-voluntary Modified Code 3.1 to its CSA raises doubts about whether Iran will report the construction of a new enrichment plant or provide design information to the IAEA as soon as it decides to construct such a facility. Iran is building a new facility in the mountains near Natanz that is deeply buried and could be a potential site for a new enrichment plant.

● The IAEA concludes that “Iran’s decision to remove all of the Agency’s equipment previously installed in Iran for JCPOA-related surveillance and monitoring activities in relation to the JCPOA has [had] detrimental implications for the Agency’s ability to provide assurance of the peaceful nature of Iran’s nuclear programme.”

● Concern about Iran’s installation of advanced centrifuges at an undeclared site increases as its 60 percent HEU stocks grow. Such a scenario is becoming more worrisome and viable, since a relatively small number of advanced centrifuge cascades would suffice for the rapid enrichment of the 60 percent HEU to weapon-grade. This hybrid strategy involves the diversion of safeguarded HEU and the secret manufacture and deployment of only three or four cascades of advanced centrifuges. With greater uncertainty about the number of advanced centrifuges Iran is making, there is a greater chance of Iran hiding away the requisite number of advanced centrifuges to realize this scenario.

● According to a separate NPT report, Iran held discussions with the IAEA in August but did not make progress in addressing the IAEA’s remaining questions about undeclared nuclear weapons activities and undeclared nuclear material found at two sites, Varamin and Turquz-Abad. Iran is stone-walling the IAEA.

● Combined with Iran’s refusal to resolve outstanding safeguards violations, the IAEA has a significantly reduced ability to monitor Iran’s complex and growing nuclear program, which notably has unresolved nuclear weapons dimensions. The IAEA’s ability to detect diversion of nuclear materials, equipment, and other capabilities to undeclared facilities remains greatly diminished.

Figure 1. The total number of advanced centrifuges installed at all three enrichment facilities. One cascade of IR-4 centrifuges was reportedly added during this quarterly report. As can be seen, centrifuge installation has been relatively minimal since February 2023.

Figure 2. The total number of advanced centrifuges deployed at the Natanz Fuel Enrichment Plant. The deployment rate remained flat between February and May 2023 quarterly reports, with only a single cascade of IR-4 centrifuges deployed during the most recent reporting period. These numbers demonstrate that Iran has made no tangible concession and, on the contrary, continued to deploy advanced centrifuges, albeit at a much slower rate than in 2022.

Read the full report here.

1. Andrea Stricker is deputy director of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies’ (FDD) Nonproliferation and Biodefense Program and an FDD research fellow. ↩

twitter

twitter