Reports

Alleged Sanctions Violations of UNSC Resolutions on North Korea for 2019/2020: The number is increasing

by David Albright, Sarah Burkhard, and Spencer Faragasso

July 1, 2020

Introduction and Summary

The United Nations Panel of Experts on North Korea (or Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK)), established pursuant to UN Security Council Resolution 1874 (2009), periodically reports its findings and recommendations on the implementation of Security Council resolutions on North Korea. These reports list in detail cases of proven or alleged sanctions violations of the UN Security Council resolutions on North Korea that have been passed by the Security Council since 2006.

The two latest reports, the final annual report dated March 2, 2020, and the midterm report dated August 30, 2019, list alleged sanctions violations the Panel investigated during its latest term, February 2, 2019, to February 7, 2020.1

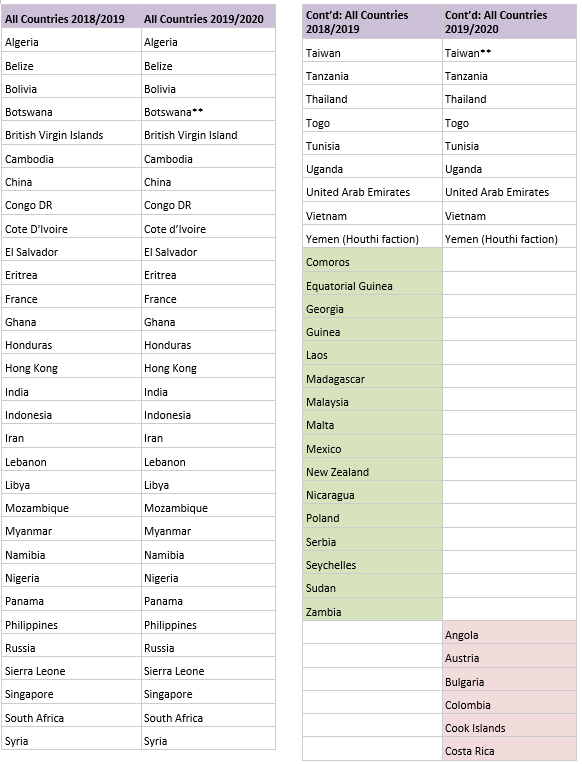

In this one-year term, here 2019/2020, the Institute identified over 250 alleged violations 2 in these two Panel reports, involving 62 countries, 3 an increase of six countries compared to the previous year’s reporting by the Institute. 4 Listed alphabetically, the 62 countries are:

Algeria, Angola, Austria, Belize, Bolivia, Botswana**, British Virgin Island, Bulgaria, Cambodia, China, Colombia, Cook Islands, Costa Rica, Cote d’Ivoire, Congo DR, Egypt, El Salvador, Eritrea, France, Germany, Ghana, Guatemala, Honduras, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Iran, Italy, Kenya, Lebanon, Libya, Luxembourg, Marshall Islands, Mozambique, Myanmar, Namibia, Nepal, Nigeria, Palau, Panama, Philippines, Qatar, Russia, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Singapore, South Africa, South Korea, Syria, Taiwan**, Tanzania, Thailand, Togo, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, Uganda, United States, Uruguay, Vanuatu, Vietnam, Yemen (Houthi faction) [**A double asterisk indicates that the country is listed only for a possible rather than an alleged violation.]

Thirty-nine of the 62 states listed in this report were allegedly responsible for multiple (two or more) documented sanctions violations. Twelve countries stand out for being involved in more than five documented allegations (listed from higher to lower number of allegations):

China, Hong Kong, Sierra Leone, Indonesia, Russia, Togo, Honduras, Vietnam, India, Italy, Panama, Singapore

China alone had over 60 alleged violations, representing almost 25 per cent of the total number of alleged violations for 2019/2020. Hong Kong followed with over 20 violations, and Sierra Leone, Russia and Indonesia each had a total of 10 or more alleged violations. The following countries had between five and ten alleged violations: Honduras, India, Italy, Panama, Singapore, Togo, and Vietnam (listed alphabetically).

Several countries are reported to have taken remedying actions since becoming aware of the violations and to have prosecuted or extradited responsible companies and individuals:

Malaysia, Palau, Singapore, South Korea, United States

Three countries stand out for having prevented sanctions violations, for example through the seizures of goods. However, this list is likely missing some countries, as not all countries involved in seizures are identified by name. The three that are identified are:

Austria, South Korea, Vietnam

Noticeably missing from either of these two categories are almost all of the countries with the most alleged violations, with the exception of Singapore and Vietnam. The other major alleged violators, including China, are not listed as having taken action to remedy any of the alleged violations.

Notable findings in the Panel’s reports:

1) The Panel summarizes North Korea’s continued collection of funds and procurement of equipment from overseas for its sanctioned WMD and ballistic missile programs, using both new and established sanctions evasion techniques. The reports highlight North Korea’s continued success in accessing the international financial system, increasing abuse of cyberspace, and large-scale busting of maritime sanctions. North Korea’s diplomatic channels remain plagued by abuse for illicit procurement activities, and short-lived front and shell companies carry on the activities of designated entities.

2) Throughout the latest one-year period, both new and long-standing sanctions were violated by North Korea and complicit or negligent countries and territories spanning several continents. Even though the latest sanctions resolution was passed over two years ago on December 22, 2017, its universal implementation has not been achieved. In contrast, the Panel reports an increase in direct maritime trade of sanctioned commodities, with China remaining the primary trading partner with the DPRK. Deadlines and requests to expel banking representatives and income-earning North Koreans living overseas have also been circumvented or ignored by several countries. These violations are particularly concerning as these earnings provide direct financial and material support for the Kim Regime.

3) Several countries have yet to respond to the Panel’s requests for information and collaboration. While not a violation, Resolution 1874, adopted by the Security Council on June 12, 2009, “urges all States […] to cooperate fully with the Committee and the Panel of Experts.”

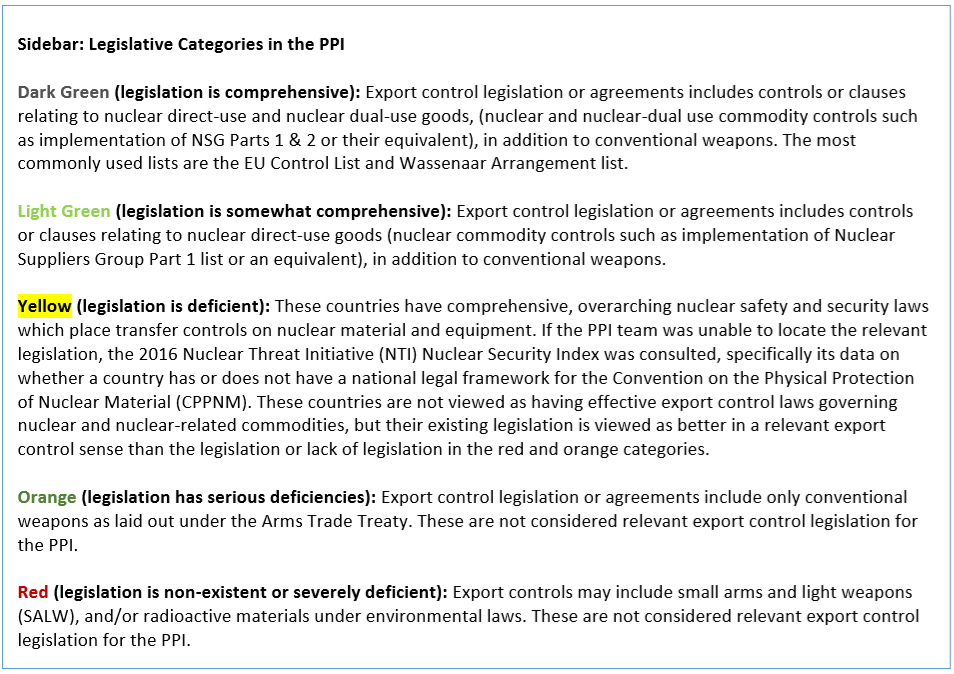

Using data and findings from another Institute study, the Peddling Peril Index for 2019 (PPI 2019), 5which biennially ranks all 200 countries, territories, and entities according to the effectiveness of their national strategic trade controls, this assessment also considers these 62 countries in terms of 1) their overall score under the PPI index, and 2) the comprehensiveness of their export control legislation, which allows for a clearer picture of the weaknesses of those involved in or caught up in alleged North Korean sanctions violations. The Peddling Peril Index serves as a tool to reinforce the norm that every country should have at least a minimal, functioning export control system and the ability to implement sectoral and financial United Nations sanctions.

Categories of Alleged Sanctions Violations

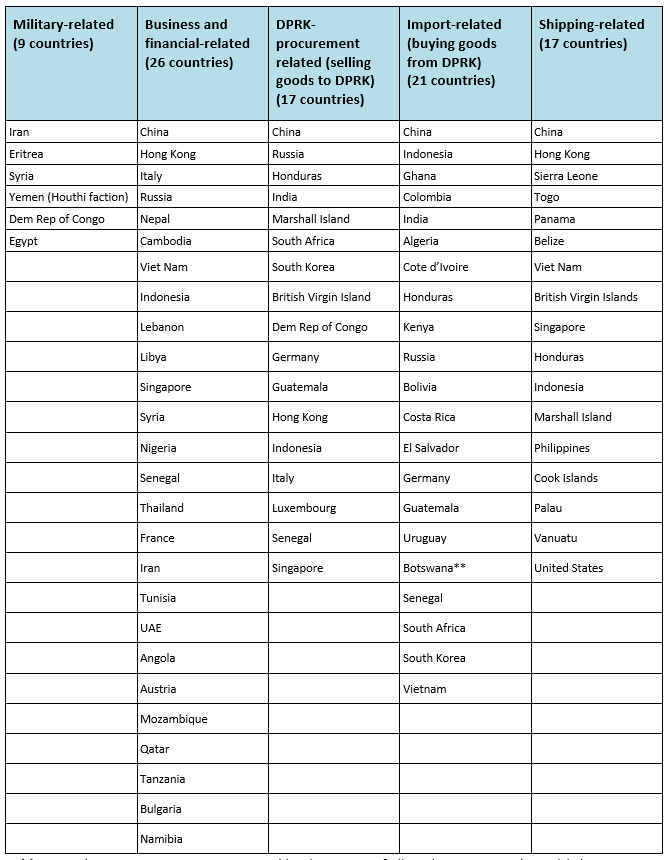

The Institute sorts the over 250 alleged violations into different categories to highlight the area(s) a listed country needs to focus on. In this analysis, alleged sanctions violations are categorized into:

• Military-related;

• Business and financial-related (including employment of North Korean workers);

• DPRK procurement-related (selling goods to North Korea);

• Import-related (buying goods from North Korea);

• Shipping-related violations (provision of transportation and related services).

These categories are consistent with categories used in previous analyses to facilitate direct comparison. Each category has sub-categories, but some sub-categories developed in last year’s analysis were not applicable to this year’s analysis, and some new ones were developed. Unresolved cases that resurfaced in the most recent reporting period with new incriminating information were included in the count.

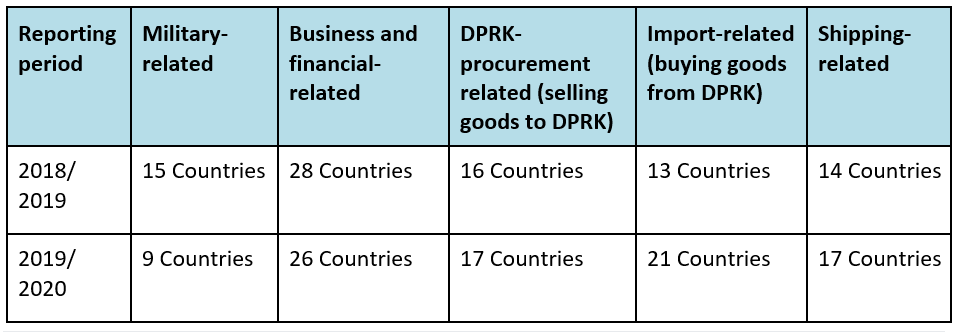

Table 1 lists the number of countries in each major category for both this reporting period and the last one, where the total number of countries increased from 56 to 62 countries. Table A.2 in the Annex provides more detail.

Table 1. Number of countries with alleged violations in five major categories in the most recent period, 2019/2020, compared to the prior period of 2018/2019. Some countries were involved in several alleged violations in more than one category.

Alleged military-related collaboration

The number of countries accused of being involved in arms sales and other military-related cooperation with North Korea is down to nine from the 15 included in last year’s analysis. The following countries fall in this category (listed alphabetically).

Congo DR, Egypt, Eritrea, Iran, Myanmar, Rwanda, Syria, Uganda, Yemen (Houthi faction)

Another country, Venezuela, appears to intend to violate the arms embargo placed on the DPRK. According to the Panel, Venezuelan government officials are suspected to have signed “a series of agreements pledging military and technological cooperation” during a visit by Venezuelan government officials to the DPRK in September 2019.

To better understand the alleged violations, this category is divided into three sub-categories:

1) States that colluded with the DPRK to procure or supply military-related equipment and materiel:

Congo DR, Egypt, Eritrea, Iran, Myanmar, Syria, Yemen (Houthi faction)

Of those, the panel emphasizes three countries alleged to host DPRK technicians “establishing a complete supply chain” for missiles:

Egypt, Iran, Syria

2) States that hosted or procured DPRK “trainers, advisors, or other officials for the purpose of military-, paramilitary-, or police related training”:

Congo DR, Rwanda, Uganda, Yemen (Houthi faction)

3) States that hosted representatives of entities designated for their activities related to arms sales:

Eritrea, Iran

The states in this category warrant special international scrutiny, as they provide a platform for the DPRK to sell arms and also make sensitive procurements for its own WMD and missile programs. According to the Panel report, “the number of DPRK procurement agents overseas is decreasing and those remaining are focusing on the procurement of critical missile related components as well as dual-use and below-threshold items.” 6 In Syria, for example, DPRK representatives are “in contact with procurement agents in a third country who can acquire specialized technological equipment.” 7

Table A.1 in the Annex lists countries identified as involved in alleged military-related cooperation with North Korea not just during this current reporting period, but also those identified in previous Institute analyses of Panel reports going back as far as 2012. Six countries appear to be at the center of ongoing military collaboration (listed three or more times over an eight-year period). They are Egypt, Eritrea, Iran, Myanmar, Syria, and Uganda.

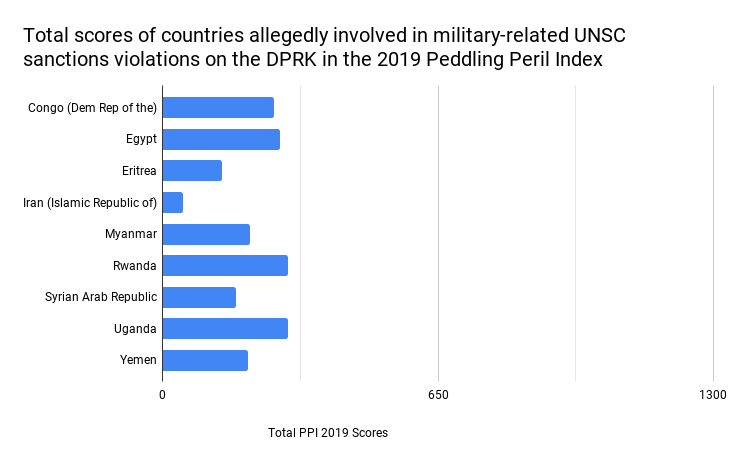

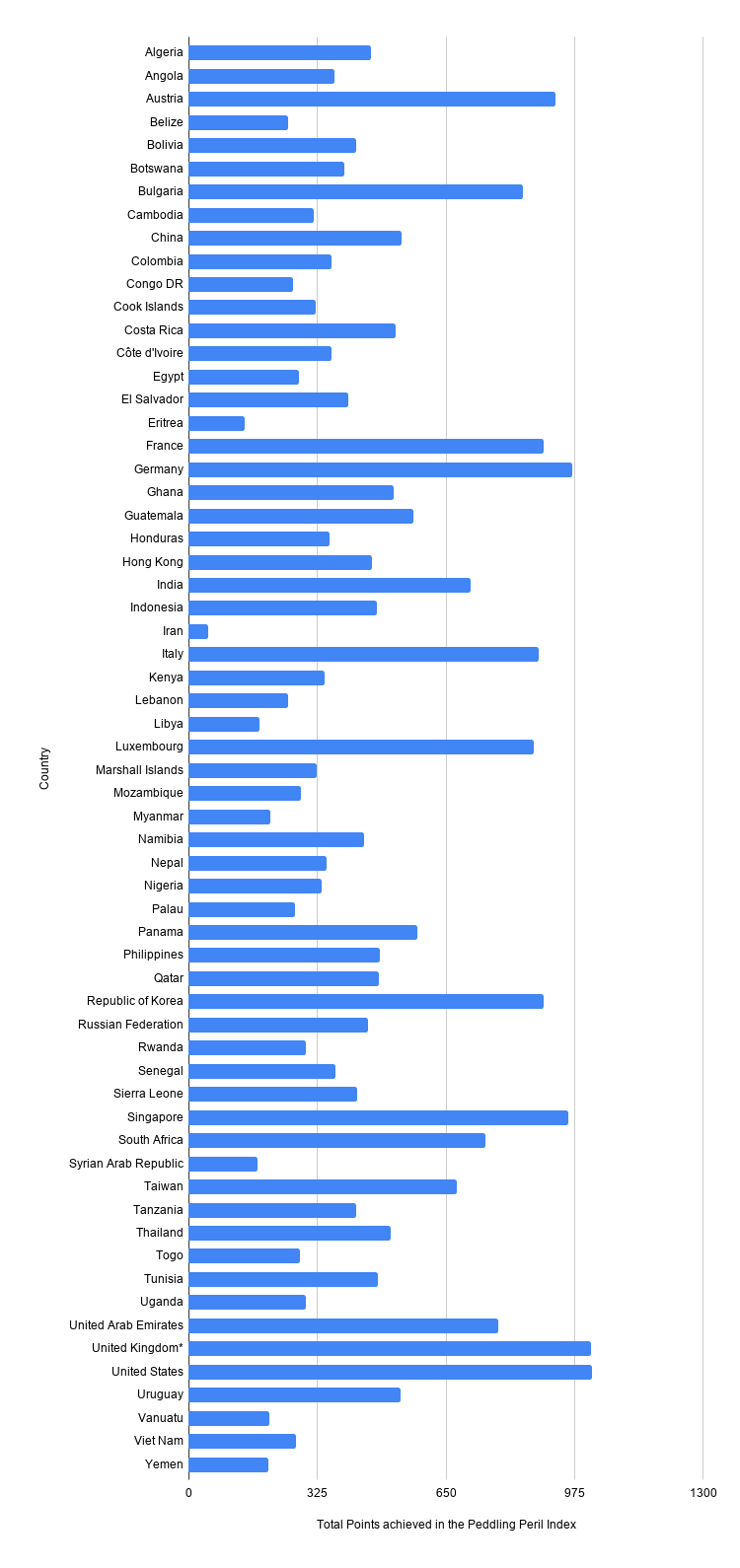

Based on the Peddling Peril Index for 2019, the group of countries involved in alleged instances of military cooperation perform poorly overall at strategic trade control implementation. The mean score of these nine states in the PPI 2019 is 211, a mere 16 percent of the available 1,300 points, with no country receiving even one-fourth of the available points (see Figure 1).

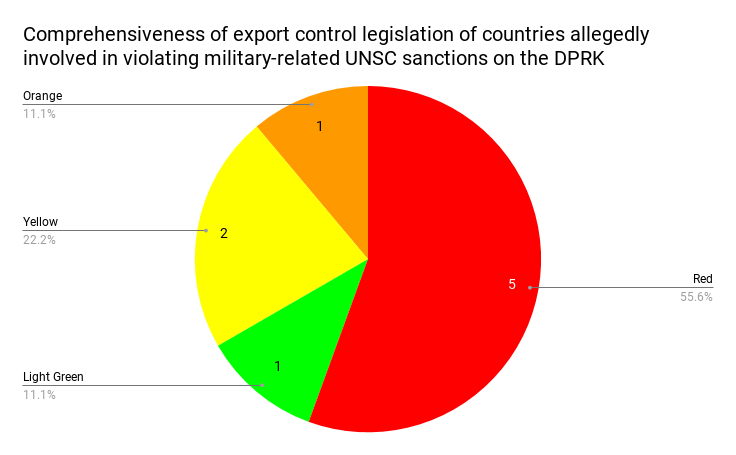

Figure 1. All nine countries alleged to have violated military-related UNSC sanctions on North Korea received fewer than one-fourth of the possible 1,300 points in the 2019 Peddling Peril Index. Eight of the nine countries have inadequate export control legislation, according to the PPI’s definitions (see side bar). Five of these countries have barely any export control legislation. This is shown in the pie chart in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Six out of the nine countries mentioned for military-related cases have no export control legislation relevant to strategic trade controls (red and orange color designation). Two have some overarching safety and security laws (yellow). Only one country has legislation categorized as light green.

Alleged business and financial-related sanctions violations

In total, the following 26 countries and territories were involved in business and financial-related sanctions violations (listed alphabetically):

Angola, Austria, Bulgaria, Cambodia, China, France, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Iran, Italy, Lebanon, Libya, Mozambique, Namibia, Nepal, Nigeria, Qatar, Russia, Senegal, Singapore, Syria, Tanzania, Thailand, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, Vietnam

The majority of all business and financial-related sanctions violations appeared to have occurred in the following countries/territories:

China, Hong Kong

The Panel reports that North Korea continues to increase its use of cyber means to collect ransom and steal money around the globe, activities also covered in detail in a recent US Department of the Treasury advisory.8 This indicates that North Korea’s focus is broadening from making financial transactions and gathering funds in traditional ways and increasing its efforts on accessing means of financing that are more anonymous and difficult to control. Many countries, most of them developing economies, reported to have been victims of North Korea’s cyber-attacks in 2019, and no indication was made that any country aided or conspired with North Korea in its efforts, although it is suspected to have collaborated with an “Eastern European cybercrime group.”9

However, there are several countries that still need to implement measures on a national level to prevent North Korea from accessing their financial systems in traditional ways, such as enforcing the required expulsion of bank representatives and the freezing of accounts of designated persons or entities, or those connected to them. The total number of countries alleged to have violated financial-related sanctions is 25.

Separate from the UN Panel report, according to a United States District Court for the District of Columbia indictment unsealed in May 2020, 33 individuals, most of them North Korean citizens, with the exception of four Chinese citizens, are accused of money laundering, operating as representatives of the DPRK’s designated Foreign Trade Bank (FTB) around the world, and making illicit US dollar transactions on behalf of the North Korean government.10 The individual cases span several years, beginning in 2013, when the US Treasury Department first sanctioned the FTB, to early 2020, when the indictment was filed. According to the indictment, the illegal transactions amounted to “at least” 2.5 billion US dollars and involved more than 250 front companies.

Some of the indicted individuals are alleged to have continued operating as Foreign Trade Bank representatives in four countries during the primary timespan this analysis covers: February 2019 to February 2020. All of these countries are already listed in this analysis as involved in alleged financial-related sanctions violations. The countries are Austria, China, Russia, and Thailand.

Financial-related sanctions violations have been further divided into five sub-categories:

1) Countries/territories whose nationals or registered entities allegedly made financial transactions on behalf of an entity related to or under control of North Korean entities (not listed elsewhere):

Hong Kong, Indonesia, Singapore

A notable example is a “blockchain enabled platform for vessel transactions” based in Hong Kong with ties to DPRK cyber actors, covered in detail in the Panel’s mid-term report.11 A Singaporean national was listed as the Chief Executive Officer (CEO), while a de-facto CEO, using an alias, appears to have been the sole decision-maker. According to the Panel, the company used at least five different front companies registered in Hong Kong to make US dollar transactions to an account held by the Singaporean national.

2) Countries alleged by the Panel report to maintain DPRK Bank relations and representation:

-Five countries are accused to have failed to expel individuals operating on behalf of DPRK banks (individuals):

China, Lebanon, 12 Libya, Russia, and Syria

-Presence of DPRK banks (offices) is alleged in the following countries:

China, Indonesia

-Banks in two countries are alleged to have affiliations with a DPRK bank:

Hong Kong, Italy

3) Countries alleged to have provided financial services (e.g. opening or allowing access to bank accounts) or to have neglected to fully enforce the asset freeze

France, 13 Italy, Russia, Tunisia

4) Countries involved in DPRK gold and cash smuggling. The following two countries are alleged to be involved in DPRK gold and cash smuggling (gold mining is categorized under North Korean procurement):

Iran, United Arab Emirates

5) Countries hosting income-earning DPRK nationals:

UNSC resolution 2397 (2017) requires countries to repatriate income-earning North Koreans immediately, but at the latest within two years (24 months) of the passing of the resolution. The two-year deadline passed in December 2019, now making hosting a DPRK citizen earning income in the host country, irrespective of visa category, a direct violation of the resolution. Further listed below are countries that do not appear to have attempted to follow the resolution’s decision to act _immediately_, as revealed by newly-issued work permits and contracts following the resolutions. The list also includes countries that are accused of circumventing the requirement of repatriation by merely relocating income-earning workers to a third state.

-One country is accused of having failed to repatriate DPRK income-earning workers by relocating them to a third state:

Russia14

-Countries alleged to host income-earning workers in the Information Technology (IT) sector (the Panel makes a note to distinguish between dispatched North Korean IT professionals earning income illicitly and those that conduct cybercrimes, who often operate from the DPRK):

Nepal, Vietnam

-Countries alleged to host income-earning workers in the medical field:

Angola, Mozambique, Nigeria, Tanzania

-Countries alleged to host income-earning North Koreans working in restaurants:

Cambodia, Nepal, Thailand

-Countries alleged to host income-earning North Korean soccer players:

Austria, Italy, Qatar

-Other sectors or areas:

China, Nigeria, Russia, Vietnam

Eight countries, some with multiple alleged violations, are listed below for alleged violations of business-related sanctions. Examples include hosting representatives of designated companies or their front companies, registering companies operated by North Korean nationals (and not already listed under shipping or military-related violations), and joint ventures.

Alleged business and company operations-related violations were further divided into four sub-categories:

1) Four states had alleged business arrangements with designated DPRK entities:

Cambodia, China, Namibia, Senegal

2) The number of investigated prohibited joint ventures and companies overtly directed by North Koreans seems to have decreased dramatically since last year. Where in our previous analysis 21 states and territories were identified as having registered joint DPRK ventures or DPRK-controlled companies, only two countries are listed below. Some countries listed in the category of hosting income-earning DPRK nationals should also be listed in this category of operating joint ventures, since, according to the Panel, in “several cases the companies arranging overseas labour are prohibited joint ventures or cooperative entities,“ but not enough information was provided. Further, this category does not include any cases listed under alleged military cooperation or procurement violations that may also have the characteristics of a joint venture.

Bulgaria,15 Nepal

3) Countries in which North Korean-operated restaurants were open:

Thailand, Cambodia, Nepal

4) Others:

China, Vietnam

DPRK procurement-related (selling goods to North Korea)

An uptick in foreign-controlled (non-DPRK) tankers delivering oil directly to ports in North Korea (discussed below, under shipping), has tangible consequences for the cap of North Korea’s allowed petroleum imports, currently at 500,000 barrels per year. According to the Panel, the cap was exceeded “many times over.”16 Other alleged banned sales to North Korea include exports of luxury items, industrial machinery, metals, and vehicles. Illegally procured technologies spotted in media footage include robotic machines (no responsible party could be identified), a drone, and a 3D printer (a form of additive manufacturing that has potential applications to WMD and ballistic missile development). No specific cases regarding North Korea’s procurement of sensitive items for its nuclear program were included in this reporting period.

While illicit procurements of commodities are frequently linked to vessel and shipping-related sanctions, the Institute chose to discuss alleged shipping-related sanctions violations, such as the provision of a flag or company registration for shipping services, separately. This was done to better differentiate between states that are primary producers, brokers, and transit points for goods sought by North Korea, and states that primarily act as shipping registrants or providers of maritime services.

The seventeen countries whose alleged involvements in sanctions evasion fall under this category are:

British Virgin Islands, China, Congo DR, Germany, Guatemala, Honduras, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Italy, Luxembourg, Marshall Islands, Russia, Senegal, Singapore, South Africa, South Korea.

The alleged illicit exports and sales to North Korea fall under six sub-categories.

1) No concrete export data for oil and related petroleum products are included in the Panel reports, which is different from the previous final Panel report of March 2019. China and Russia are the only countries listed as having reported oil and petroleum shipments to North Korea to the Panel as required by the resolutions. Sierra Leone reported some of the observed shipments, but it is not clear where the oil was exported from. One company based in Taiwan appears to have been the purchaser of a shipment of petroleum before its delivery to North Korea in February 2019, even though no official shipments from Taiwan were reported to the Panel.

2) The ban on selling luxury items to North Korea was allegedly violated by entities in several countries. In these cases, the manufacturing country is not listed if there is supporting information that they were unaware of the final destination of its goods, rather, the diversion point is listed as responsible party. In one case, concerning _Lexus_ vehicles spotted in North Korea, not enough information was provided to identify a responsible party.

British Virgin Islands, China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Italy, Marshall Islands, South Korea

-Of those, countries whose entities were involved in the delivery of two armored Mercedes Benz to North Korea include:17

Italy, Marshall Islands, South Korea

-Countries whose entities were involved in the procurement of liquor, such as vodka:18

China, Hong Kong

3) Countries involved in technology procurements as spotted at a trade fair in North Korea (a drone and a 3D printer):

China

4) Countries hosting North Korean professionals for collaboration on emerging technology development (artificial intelligence hardware and software):

China

5) The report also highlighted DPRK involvement in gold mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Congo DR

6) Other sanctioned commodities exported to North Korea:

Some countries responded, explaining that the trade data reported is incorrect, denying that the exports occurred as reported in the two major global trade databases the Panel uses, the Trade Map of the International Trade Centre (ITC) and the Global Trade Atlas. In several cases, countries claimed that the data entry is the result of human error in customs declarations. The Institute decided to include only countries that did not provide an explanation for the data.

Alleged violations of export bans based on reported trade in those Harmonized System (HS) chapters that are listed in the UN sanctions factsheet as sanctioned:19

-Industrial Machinery (HS 84 – 85):

Germany, Honduras, India, Luxembourg, Russia, South Africa

-Metals (HS 72 – 83):

Honduras, Guatemala, India, Russia, Senegal, South Africa

-Vehicles (HS 86 – 89):

Russia

Shipping-related violations (providing transportation)

Faced with global port bans, DPRK-flagged vessels rely on foreign-flagged vessels to transport illicit cargo (such as undeclared petroleum shipments) at least part of the way, whether goods are entering or exiting North Korean waters. According to the Panel, North Korea and complicit countries continued to use ship-to-ship (STS) transfers and “well-documented evasion techniques, including Automatic Identification System [AIS] turn-off; physical disguise; the use of small vessels without [International Maritime Organization] IMO numbers, name-changing, night transfers and other forms of identity fraud,” as well as new techniques, such as using a different class of AIS transponder, designed for smaller ships like fishing boats, which has a shorter range for broadcasting the ship’s location.

China remained at the forefront of direct maritime trade with North Korea, also using both new and established techniques to transport the goods. New techniques, for example, are the frequent use of Chinese “self-propelled ocean-going barges” that do not require IMO numbers and are able to return to China’s rivers to deliver DPRK coal directly to its customers, as well as ship-to-ship transfers in the Ningbo-Zhoushan, or Lianyungang area. According to the report, these activities “likely contribute to reducing the country’s vessels’ exposure to scrutiny.”

Most of the remaining shipping-related violations stemmed from so-called “Flag of Convenience” countries, countries with open ship registries that allow foreign nationals to register their vessels, and jurisdictions that enable company registrations with similarly little oversight. Open ship registries are a source of income for several small countries, but they often lead to a lack of oversight, demonstrated by their misuse for sanctions evasion.

Foreign-flagged bulk carriers delivering directly to North Korea are especially worrisome, as they circumvent time-consuming and risky ship-to-ship transfers with North Korean vessels. Thus, sanctions violations are enabled on a larger scale.

Further, the Panel highlights a “relatively new phenomenon” where foreign-flagged vessels delivering directly to DPRK ports receive their cargo in ship-to-ship transfers from other foreign-flagged vessels, likely unaware of the final destiny of their cargo. These “supplier vessels,” as the Panel calls them, are not included in the country list below, but the practice is worrisome as foreign-flagged vessels are able to further increase volume and speed of their illicit deliveries to North Korea using this technique.

In total, 17 countries were involved:

Belize, British Virgin Islands, China, Cook Islands, Honduras, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Marshall Islands, Palau, Panama, Philippines, Sierra Leone, Singapore, Togo, United States, Vanuatu, Vietnam

The documented shipping-related alleged sanctions violations are sorted into five sub-categories.

1) Per resolution 2379 (2017), UN member states are also prohibited from selling used vessels to the DPRK. Still, in June 2019, North Korea succeeded in buying a vessel designated for scrap at a substantial price markup. Countries involved in this acquisition:

China

2) Countries with registered flagged vessels that engaged in ship-to-ship transfers or direct deliveries from or to North Korea:

Belize, China, Cook Islands, Honduras, Palau, Panama, Sierra Leone, Togo, Vanuatu, Vietnam

3) Flagging a ship after deregistration is explicitly prohibited. One case is highlighted in which a state registered a vessel after it was deregistered by another state, even if it was temporary:

Sierra Leone

4) The Panel reveals a pattern of short-lived companies listed on vessel registries as companies owning, managing, or providing other maritime services for vessels suspected to be involved in sanctions evasion schemes. According to the midterm report, these companies “appear to be recently established shell or front companies listed under third-party ship operators in a different jurisdiction.” In UN resolutions, countries are held responsible for the companies registered in their jurisdiction. For example, according to Resolution 2375(2017), “all Member States shall prohibit their […] entities incorporated in their territory or subject to their Jurisdiction […] from facilitating or engaging in ship-to-ship transfers to or from DPRK-flagged vessels.” [italics added]

Countries that failed to prohibit entities registered or operating in their territorial jurisdictions from facilitating or engaging in ship-to-ship transfers or direct deliveries:20

British Virgin Islands, China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Marshall Islands, Philippines, Singapore, Togo, Vietnam

5) Countries through which payments related to vessels and shipping were routed (not listed elsewhere):

United States

Import-related (buying goods from North Korea)

The Panel reported a general increase in illicit exports, and specifically in the illicit export of coal from North Korea. Here, too, China remains North Korea’s primary trading partner, and is not only providing transport for the illicit coal, as discussed above, but also buyers. Further, Chinese customers are alleged to have imported sand from the DPRK, another sanctioned commodity under UNSC sanctions provisions banning North Korea’s export of earth and stone.

The 21 countries whose alleged involvement in sanctions evasions fall under this category are:

Algeria, Bolivia, Botswana**, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cote d’Ivoire, El Salvador, Germany, Ghana, Guatemala, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Russia, Senegal, South Africa, South Korea, Uruguay, Vietnam [A double asterisk indicates a country is listed only for a possible rather than an alleged violation.]

The alleged violations are organized into four sub-categories.

1) Countries listed as having imported coal:

China, South Korea, Vietnam

One country returned DPRK coal to a broker of its nationality who attempted to re-sell it using false declarations of origin:

Indonesia

2) Countries alleged to have imported earth and stone illicitly:

China

According to the final Panel report, since May 2019, “over a 100 shipments” of sand originating in North Korea went to different Chinese ports.21 Sand imports are prohibited under the ban on earth and stone, and while sand is not an expensive commodity, the sheer volume is estimated to have amounted to a value of $22 million dollars or more.

3) Alleged imports of sanctioned goods based on global trade data:

Alleged violations of import bans based on reported trade in those HS chapters that are listed in the sanction’s factsheet as sanctioned:

-Electrical equipment (HS 85):

Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Russia, Germany

-Machinery (HS 84):

Algeria, Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Ghana, Guatemala, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Russia, Senegal, Uruguay

4) _Possible_ violations based on reported trade in HS chapters which cover banned goods but may also include goods that are not banned:

-Copper (HS 74, 2603):

Indonesia

-Iron, iron and steel products (HS 72, 73):22

Algeria, Botswana, Colombia, China, Cote d’Ivoire, El Salvador, Germany, Ghana, Guatemala, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Russia

-Metals (HS 72-83):

South Africa

-Seafood (HS 03, 1603-1605):

Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana

-Textiles (HS 50-63):

Algeria, Colombia, Ghana, Indonesia, Kenya, Uruguay

-Zinc (HS 79):

India

Countries’ performance in the 2019 Peddling Peril Index

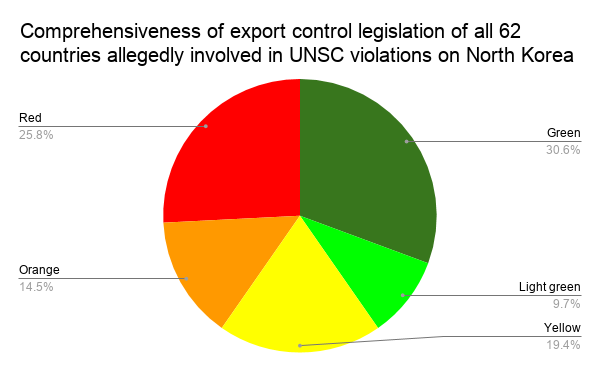

All 62 countries together have an average score of 475, fourteen points lower than the average of all 200 countries in the PPI. The median of 423 points is lower yet, and 20 points lower than the overall median in the PPI. Figure 3 shows the quality of their national export control legislation. Figure 4 shows the PPI scores for all 62 countries.

Figure 3. Countries involved in alleged sanctions violations have export control laws of varying depths, some covering nuclear direct and dual-use items (dark green), others not even adequately covering conventional weaponry (red).

Figure 4. PPI scores of the 62 countries with alleged violations. Out of the 62 countries, almost one-third received fewer than a quarter of the possible 1,300 points in the PPI. Over three-quarters of the 62 countries received fewer than half of the available points. Note: The PPI does not evaluate overseas territories separately from the country proper, which means that the PPI score for the United Kingdom is used for the British Virgin Islands.

Recommendations

Both Panel reports include a number of excellent recommendations for the Sanctions Committee and UN member countries to strengthen implementation of the series of UNSC resolutions on North Korea. Several recommendations follow, some of which overlap with the Panel’s recommendations.

The UN Security Council should accelerate the designation of entities and vessels recommended by the Panel.

To facilitate compliance with sectoral bans and investigation of possible sanctions evasion, the Sanctions Committee should address and reduce the ambiguity around some of the goods covered by the sectoral sanctions by adding the relevant HS codes to the Fact Sheet, as appropriate.

The amount of information processed by the Panel of Experts on North Korea is impressive; the Panel’s mandate should continue, and it should continue to receive assistance from the Security Council and the Sanctions Committee. In 2013, the Panel increased its staff from seven members to eight. 23 If the Panel needs more resources to investigate the increasingly complex sanctions evasions, the Security Council should dedicate additional resources to this important effort.

The Panel reports and our analyses show that many states/territories are alleged to be violating UNSC sanctions on North Korea. It is necessary for all states, but especially states listed above, and states where violations continue to occur throughout the years, often in the same categories, to take proper due diligence to enforce international sanctions and verify their compliance. No safe harbors should support North Korea in its quest to develop its nuclear and ballistic missile programs.

The states involved in arms sales and other military cooperation with North Korea warrant special international scrutiny, including economic penalties. Six of those states have stood out regularly in the Panel reports during the last eight years. States violating these sanctions provide a platform for North Korea to sell arms and also make sensitive procurements for its own WMD and missile programs. Restricting the spread of specialized technological equipment is a necessary action that will further constrain the DPRK’s ability to acquire equipment. Actions like those will force the DPRK to pursue other and possibly more complicated and costly means of acquiring such equipment.

Several violations in this report could have been prevented by additional due diligence. The Panel recommends practices including confirmation of port call destinations, usage of certificates of ultimate origin and ultimate destination, and the verification of documentation. Further, countries need to regulate and vet their company and ship registries to not attract shell and front companies providing a platform for illicit maritime activities. For example, the Palau ship registry demonstrates that due diligence can reduce the misuse of an open ship registry for sanctions evasion. According to the Panel report, the registry attempted to track a vessel in its registry after it stopped transmitting its location via its AIS, and used a regional Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to ask Chinese port authorities to hold the vessel at a port for inspection.

North Korea continues to employ income-earning workers overseas, knowingly or unknowingly by the host country. All states, especially those that are documented to have current or past DPRK income-earning workers operating in their territory, should take extra care to ensure that all income-earning DPRK nationals are repatriated.

North Korea continues to advance the complexity of its sanctions violation schemes, using cyberspace and other means, such as complex ship-to-ship transfer schemes, to avoid detection and procure funds/materials for its nuclear and ballistic missile programs. Strengthening cybersecurity systems may help reduce the prevalence of cyber theft by the DPRK. States should continue to develop capabilities to monitor and prevent the use of cryptocurrency for money laundering purposes by illicit actors in the DPRK.

It is important to note that even during the deadly coronavirus pandemic, countries should maintain strict implementation of UN sanctions and resolutions. Times of crisis present new opportunities for illicit actors in the DPRK to take advantage of financial systems and decreased trade facilitation monitoring activities. Medical aid and humanitarian assistance should be delivered, but related transfers should occur via designated channels to prevent any misuse.

Annex: Summary Tables of Alleged Violations

Table A.1 lists countries allegedly involved in military-related cooperation with North Korea, by reporting period, including previous Institute analyses of Panel reports. Six countries appear to be at the center of ongoing military collaboration (listed three or more times over an eight-year period). They are Egypt, Eritrea, Iran, Myanmar, Syria, and Uganda.

Table A.2 lists the number of countries in each of the five major categories, listed from top to bottom in order of the number of recorded cases. (Table 1 in the main section of the report summarizes the numbers of countries in each major category.) Table A.3 is a comparison of countries involved in alleged sanctions violations in 2018/2019 compared to 2019/2020.

Table A.1. Countries allegedly involved in military-related cooperation, by reporting period and in previous Institute analyses. Six countries appear to be at the center of ongoing military collaboration (listed three or more times).

Table A.2. The 62 countries are categorized by the nature of alleged sanctions violation(s) they were involved in for the period 2019/2020. Countries are listed from top to bottom by number of recorded cases.

Table A.3. Countries involved in alleged sanctions as reported in the 2018 reporting period, compared to those listed in 2019, listed alphabetically. Marked in green are the 16 countries that do not appear in our 2019 list after appearing in 2018, marked in red are the 22 countries that newly appeared in our 2019 list but were not listed for 2018. No color means that the country is listed for both years. [**A double asterisk indicates that the country is listed only for a possible rather than an alleged violation.]

1. Find the Panel reports here: United Nations Security Council, 1718 Sanctions Committee (DPRK), “Reports,” https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/1718/panel_experts/reports . The reporting period is February 2019 to February 2020, but the final report includes trade data spanning April 2018 - September 2019, which became newly available during the reporting period. ↩

2. The exact number of violations is difficult to determine and our count only includes cases with concrete information on individual cases. Where individual case information was missing, but a pattern and a responsible country were identified, this was counted as one violation. For example, China’s imports of DPRK-origin sand, estimated to have occurred through “over 100 illicit shipments,” are bundled here as one violation. ↩

3. Excluding North Korea and violations solely committed by North Korea. ↩

4. See David Albright, Sarah Burkhard, Bernadette Gostelow, Maximilian Lim, and Andrea Stricker, “56 countries involved in violating UNSC Resolutions on North Korea during last reporting period,” Institute for Science and International Security, June 6, 2019, https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/56-countries-involved-in-violating-unsc-resolutions-on-north-korea-during-t/ ↩

5. See: David Albright, Sarah Burkhard, and Andrea Stricker, Peddling Peril Index for 2019: Ranking National Strategic Export Control Systems (Washington, D.C.: Institute for Science and International Security, 2019), http://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/The_Peddling_Peril_Index_Final_May2019.pdf ↩

6. UN Security Council, Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1874 (2009), S/2019/601, August 30, 2019, pg. 138, https://undocs.org/S/2019/691 ↩

7. Ibid. ↩

8. U.S. Department of Treasury, Guidance on the North Korean Cyber Threat, April 15, 2020, https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/Programs/Documents/dprk_cyber_threat_advisory_20200415.pdf ↩

9. UN Security Council, UN Panel of Experts on North Korea, established pursuant to UNSCR 1874 (2009), S/2020/151, March 2, 2020, pg. 65, https://undocs.org/S/2020/151 ↩

10. United States District Court for the District of Columbia, United States of America v. Ko Chol Man et al., unsealed in May 2020, https://int.nyt.com/data/documenthelper/6971-north-korea-indictment/422a99ddac0c39459226/optimized/full.pdf#page=1 ↩

11. S/2019/601, pg. 29-30. ↩

12. The Panel reports two DPRK bank representatives based in Syria as having travelled through and operated in Lebanon under aliases. ↩

13. France is listed for not fully enforcing the asset freeze on rental income by Reconnaissance General Bureau agent Kim Sou Gwang. Further, while France closed the bank account of Reconnaissance General Bureau Kim Yong Nam in April 2017, the remaining funds were not frozen, but transferred to an overseas account in Russia, for which Russia is listed in this category. See: S/2019/691, pg. 25; S/2020/151, pg. 63. ↩

14. Amie Ferris-Rotman, “In breakaway Abkhazia, a loophole for North Korean workers amid beaches and Soviet relics,” October 13, 2019, The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/in-breakaway-abkhazia-a-loophole-for-north-korean-workers-amid-beaches-and-soviet-relics/2019/10/12/7e203290-d7b8-11e9-a1a5-162b8a9c9ca2_story.html?fbclid=IwAR0dSTQ_i64h_8k2anX64ZiSGpwg5PWsFGM6xrszFTSVSJUQN0Bt8INtjs8 ↩

15. In Bulgaria, a China-registered company, suspected to be a front company for a designated North Korea entity, formed business relations with a Bulgarian-registered company. The prohibited cooperation may have occurred unwittingly, whereas the front company provided obscured and deceptive information in order to facilitate the business venture. Bulgaria has since investigated the relationship and subsequently deregistered the joint venture, including expelling any associated DPRK nationals. DisplayedText ↩

16. S/2020/151, pg. 4 ↩

17. A freight forwarder from the Netherlands may have acted as negligent facilitator of this violation. Several instances should have caused suspicion, including a denial by Chinese port authorities to allow the transshipment of the vehicles and subsequent changes of consignees. ↩

18. It is unclear whether the manufacturer based in Belarus was aware of the intended final destination. ↩

19. See: Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1718 (2006), “Fact Sheet compiling certain measures imposed by Security Council resolutions 1718 (2006), 1874 (2009), 2087 (2013), 2094 (2013), 2270 (2016), 2321 (2016), 2356 (2017), 2371 (2017), 2375 (2017), and 2397 (2017),” April 17, 2018, https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sites/www.un.org.securitycouncil/files/fact_sheet_updated_17_apr_2018_0.pdf ↩

20. The chain of ownership of the Rui Hong 916, a vessel conducting a ship to ship transfer with a DPRK vessel in May 2019, is obscure, but there are indications that a Japanese entity or an entity related to it was the owner of the vessel at the time. ↩

21. S/2020/151, pg. 36. ↩

22. China and Germany responded that they consider these imports to be in compliance with the UNSC resolutions. > ↩

23. Letter dated 20 December 2019 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1718 (2006) addressed to the President of the Security Council, S/2019/971, December 20, 2019, https://www.undocs.org/S/2019/971 ↩

twitter

twitter