Reports

A Strategic Challenge: A Peddling Peril Index Analysis of Countries’ Restricted Russia Trade

by David Albright, Sarah Burkhard, and Spencer Faragasso

July 10, 2023

Background

National trade control systems and sanctions enforcement across the globe have been particularly challenged by Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, the unexpected types and number of goods to control, the need for rapid control of those items, and Russia’s determination to thwart others’ trade controls. The Russian situation demonstrates that even countries with strong strategic trade control systems have vulnerabilities.

In the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the results of the Peddling Peril Index (PPI) for 2021/2022 provide a method to assess a total of 31 countries identified by their respective roles in the transshipment of restricted goods or the supply of dual-use goods used by the Russian military.

The purpose of this study is to identify patterns in these countries’ scores and lessons in finding ways of thwarting Russia’s success in violating sanctions and export controls.

Findings and Recommendations

More action is needed to thwart Russia’s illicit acquisition of goods. The mature export control systems in many states provide a sound basis to create more effective tools to act against Russia’s threat to the system of international trade and security. At the same time, these countries can press nations with inadequate transshipment controls to both improve them and participate more actively in thwarting Russia’s illicit trade.

The most immediate challenge posed by Russia‘s illicit trade activities is transshipment, which involves almost two-thirds of the countries in this list of 31. One subgroup of countries identified as transshipment points for goods destined for Russia that also have poor enforcement PPI rankings includes China, Brazil, India, Turkey, Armenia, Uzbekistan, and Nicaragua. Kyrgyzstan is also included in this group due to its failure to adjust its controls to compensate for its membership in the Russian customs union that minimizes customs controls on goods destined for Russia.

One subgroup on the list of 31 countries stands out as supplying Russia with munitions and military equipment for use in its war in Ukraine—Belarus, Iran, North Korea, and Syria, all of which traditionally rank poorly in the PPI. These countries require more sanctions, and vigilance is needed to prevent this list from growing.

The Institute’s list of countries that have played a role in supplying Russia contains both supplier countries and transshipment countries. No country that was not already classified by the PPI as having dual-use supply or transshipment potential was identified.

Many of the 31 countries considered in the study, and particularly among a subgroup of 20 responsible countries classified by the PPI as having high supply potential, have high PPI scores, indicating that their general strategic trade control regulatory environment is strong. They are ideally suited to expand their cooperation to improve controls against Russia and take steps, collectively and individually, to gather allies among responsible members of multinational export control regimes and others with relatively high scores on the PPI, and convince transshipment countries to desist allowing goods to pass through their countries to Russia.

High-scoring, responsible countries can be expected to continue working diligently to recalibrate their approach to Russian trade in terms of more listed strategic goods, expanded enforcement, better end-user and end use checks, more scrutiny and enforcement of illegal financial arrangements used by Russia, its oligarchs, and its agents, enhanced international cooperation, expanded industry/government cooperation, and intelligence sharing about illicit networks and goods. Several suggestions in these areas are included in the recommendations section of the report.

Governments, typically high-scoring ones, such as the United States, Germany, and others in the European Union are taking important steps against transshipments to Russia, but these steps have not proven sufficient to stem the tide of restricted goods.

All supplier countries should consider another approach tested by the United States several years ago. For countries of transshipment concern, major supplier governments should promptly issue draft regulations for these countries to be designated officially as “destinations of diversion concern” if they do not take quick and decisive action. Such a designation would trigger far greater scrutiny of a wide range of exports, not just sensitive ones, to that country, providing an incentive for the country to rapidly improve its ability to provide assurance that transshipment of items prohibited for Russia will not occur. The logic is simple—if the transshipment country will not act, then the most affected supplier country must.

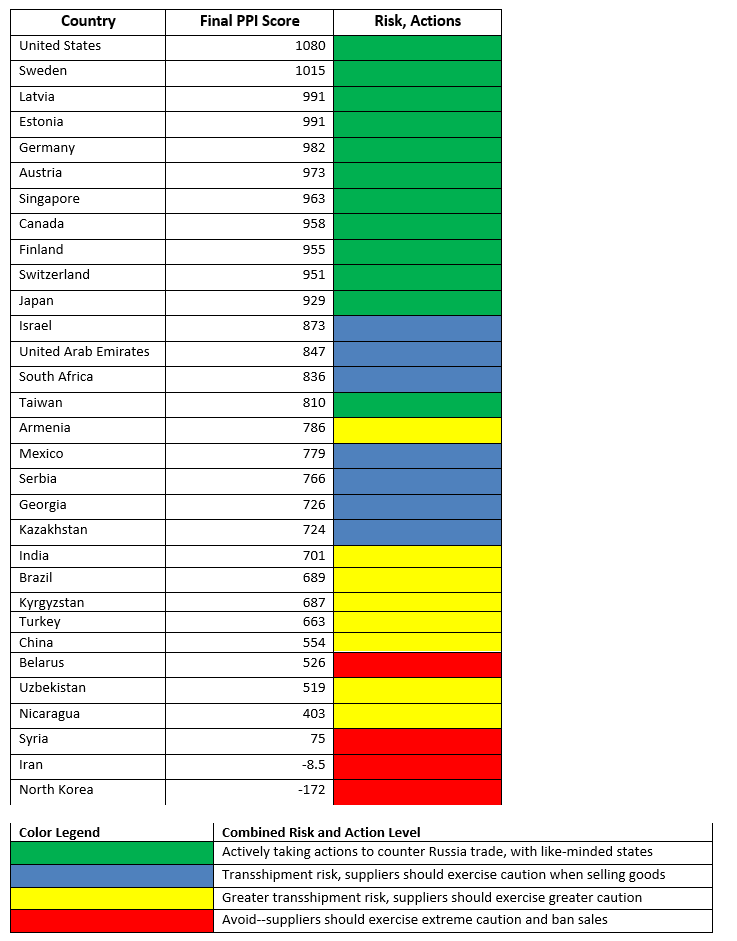

Individual suppliers currently need to exercise extra caution in selling goods internationally for fear of them ending up in Russia. At the end of the report, table 2 summarizes the risk the 31 countries pose to suppliers.

Introduction

Russia poses a complex challenge to national and multilateral systems of trade controls and sanctions. Russia has traditionally been viewed as a compliant member of the Nuclear Supplier Group and other multilateral control regimes, and a leader in efforts to stop the proliferation of nuclear weapons. Post-Soviet Russia was welcomed into global supply chains, becoming an important trade partner of many European and Asian countries. That status has been disrupted by its invasion of Eastern Ukraine and annexation of Crimea in 2014 and much more so by its second invasion of Ukraine in 2022, starting a war of aggression that has been ongoing since February of 2022.

National trade control systems and sanctions enforcement across the globe have been particularly challenged by the perceived suddenness of Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, the unexpected types and numbers of goods to control, the need for rapid control of those items, and Russia’s determination to thwart others’ trade controls. Countries have been called upon to respond to the changing trade environment with Russia, following decades of trade and investment, as Russia has accelerated its import and export of restricted items through deceptive and illicit pathways. Overall, that response has so far been subpar, even among those nations most committed and able to stop illicit trade in dangerous goods.

Many countries have been identified as being involved in or facilitating Russia’s efforts to import and export dual-use and restricted items. Some countries have even provided weapons and other munitions to Russia for use in its war in Ukraine. This report assesses these countries considering their scores and rankings in the 2021/2022 Peddling Peril Index (PPI), which ranks national strategic trade control systems. The purpose is to look for patterns in their scores and draw lessons in finding better ways of thwarting Russia’s ongoing successes in violating sanctions and export controls.

The Peddling Peril Index for 2021/2022

The Peddling Peril Index for 2021/2022 is the third edition in a biennial series assessing the commitment and ability of countries worldwide to support nonproliferation and strategic trade control measures.1 Countries that achieve higher scores in the PPI show a greater commitment to supporting and implementing strategic trade controls and nonproliferation measures, including international treaties.

The PPI measures countries’ performance across five overarching super criteria: International Commitment, Legislation, Ability to Monitor and Detect Strategic Trade, Ability to Prevent Proliferation Financing, and Adequacy of Enforcement. Each of 200 countries and entities receive a score and a ranking, with a maximum score of 1300. Countries are also ranked within one of three Tiers: Tier 1 countries are those that possess nuclear facilities, nuclear weapons, knowhow, and can supply dual-use items and strategic materials—almost exclusively Nuclear Supplier Group (NSG) members; Tier 2 countries are those countries that pose a transshipment risk; and Tier 3 countries are all other countries. It should be noted that Tier 1 countries can also pose a significant transshipment risk, but membership in Tier 1 and 2 is mutually exclusive and determined by its primary characteristic.

PPI Scoring vs. Russian Trade of Strategic Commodities

A total of 31 countries have been identified for analysis, selected by their respective roles in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Some of these countries are involved in the transshipment of restricted goods; others are listed for their supply of dual-use goods used by the Russian military. Iran and a few others are listed for their direct supply of weapons and ammunition to Russia. This group of 31 countries is composed of four related sub-groups:

1) The United States Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) identified 17 countries as “common transshipment points through which restricted or controlled exports have been known to pass before reaching destinations in Russia or Belarus.”2

Armenia, Brazil, China, Georgia, India, Israel, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mexico, Nicaragua, Serbia, Singapore, South Africa, Taiwan,3 Turkey, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Uzbekistan

2) Additional transshipment countries identified by the Institute, and not mentioned above or below, as involved in providing restricted commodities to Russia. 4

Estonia, Finland, and Latvia

3) Additional countries, not included in the first two sub-groups, were added, since they were assessed by the Institute to have supplied dual-use goods found to be used in Russia’s military programs, including its WMD and missile programs or in military drones deployed against Ukraine. Note: China and Taiwan are omitted in this group because they are already in Group 1.

Austria, Canada, Germany, Japan, Sweden, Switzerland, and United States

There are additional supplier countries that reportedly exported dual-use goods to Russia, but it is unclear if these goods were used in Russia’s military programs or are restricted. These countries are thus excluded from this analysis, pending additional information. They include Bahrain, Malaysia, Pakistan, South Korea, and Spain.

The Institute also did not add countries reportedly involved in financial sanctions evasion (such as Cyprus), offshore shipping transfers of Russian oil (including Cyprus, Greece, and Malta) or illegal shipments of grain stolen by Russia in Ukraine to third countries (including Libya and Lebanon.)

4) At least four countries have supplied Russia with munitions and military equipment for use in its war in Ukraine.

Belarus, Iran, North Korea, Syria

There are other countries that are alleged to have supplied military goods to Russia. In particular, South Africa is reported to have supplied military goods to Russia, where the media attributes the information to U.S. intelligence. A South African investigation has yet to report. Egypt was not included in this report because a suspected missile deal was canceled, and the weapons were never supplied.

Average PPI Scores of all Countries in the Four Groups

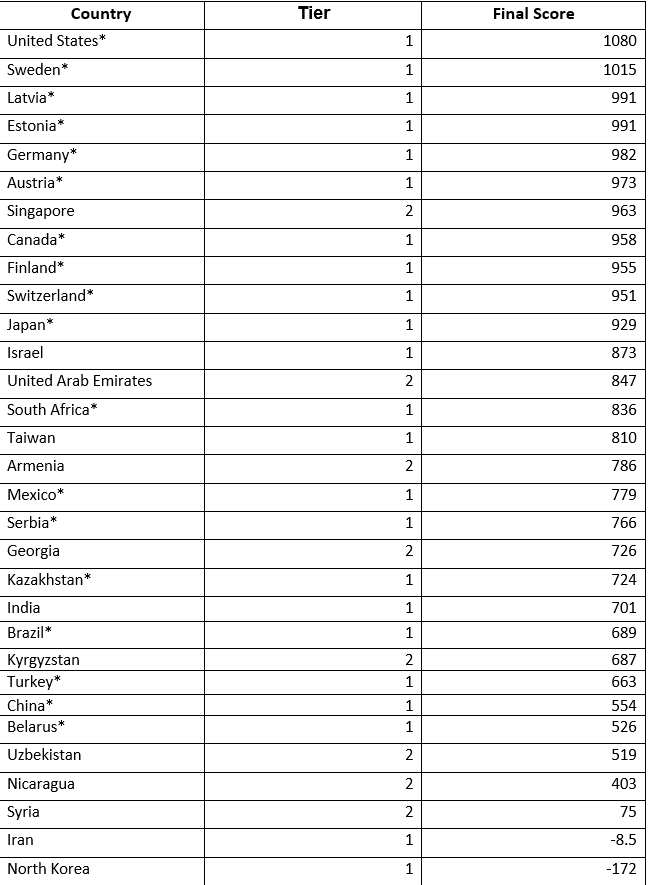

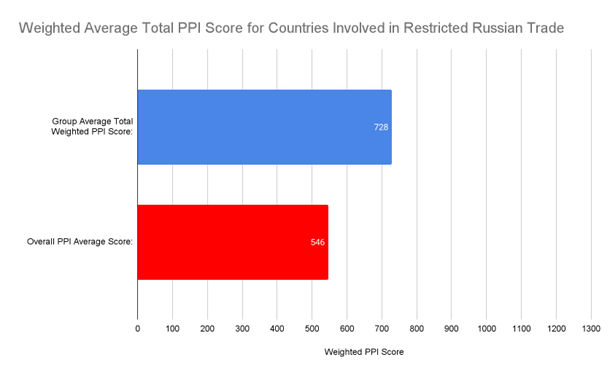

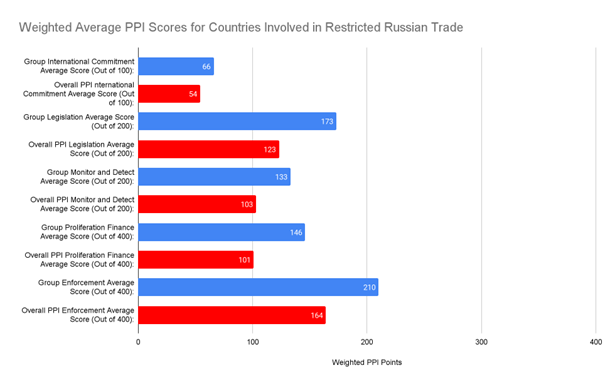

Table 1 shows the entire list of these 31 countries, organized by PPI score and tier. When assessing the group of 31 countries in Table 1, it becomes clear that, on average, they had a higher global overall score in the PPI and outperformed the global PPI average in every super criterion (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Twenty-four of the 31 countries received more than 50 percent of the total points out of 1300, with Iran and North Korea receiving negative scores. The relatively high scores among these twenty-four countries reflect their overall high level of strategic trade controls, although the scores also show that all their systems can be improved.

Twenty-three of the 31 countries are in Tier 1, meaning they have a greater supply potential for nuclear and dual-use materials. Eighteen of the 23 Tier 1 countries are Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) members; the remaining five countries of this subgroup also have significant supply potential. Eight are in Tier 2, meaning they have great transshipment potential. None of these 31 countries is in Tier 3.

Table 1. Tier and PPI Score of Countries Identified with a Role in Supplying Russia 5

Figure 1. The group of 31 countries’ average PPI score, aka weighted average score, vs. the global average PPI score.

Figure 2. The overall scores in each respective super criterion for the group of 31 countries compared to the global PPI scores in each super criterion.

Responsible Tier 1 Subgroup

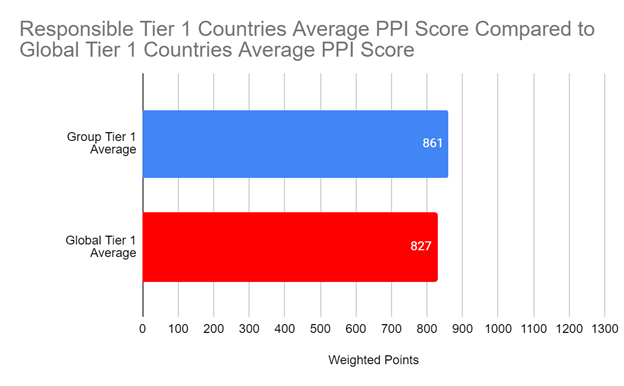

It is worth delving deeper into the scores of the subgroup of Tier 1 countries and comparing them to the average scores of all Tier 1 countries. But before doing that, it is useful to remove from the averaging process three problematic Tier 1 countries–Iran, North Korea, and Belarus. These three countries have low scores and often flaunt international standards of acceptable behavior. They are also linked to providing military equipment to Russia. Eliminating these three countries allows for a focus on the more responsible countries concerned about supply to Russia.

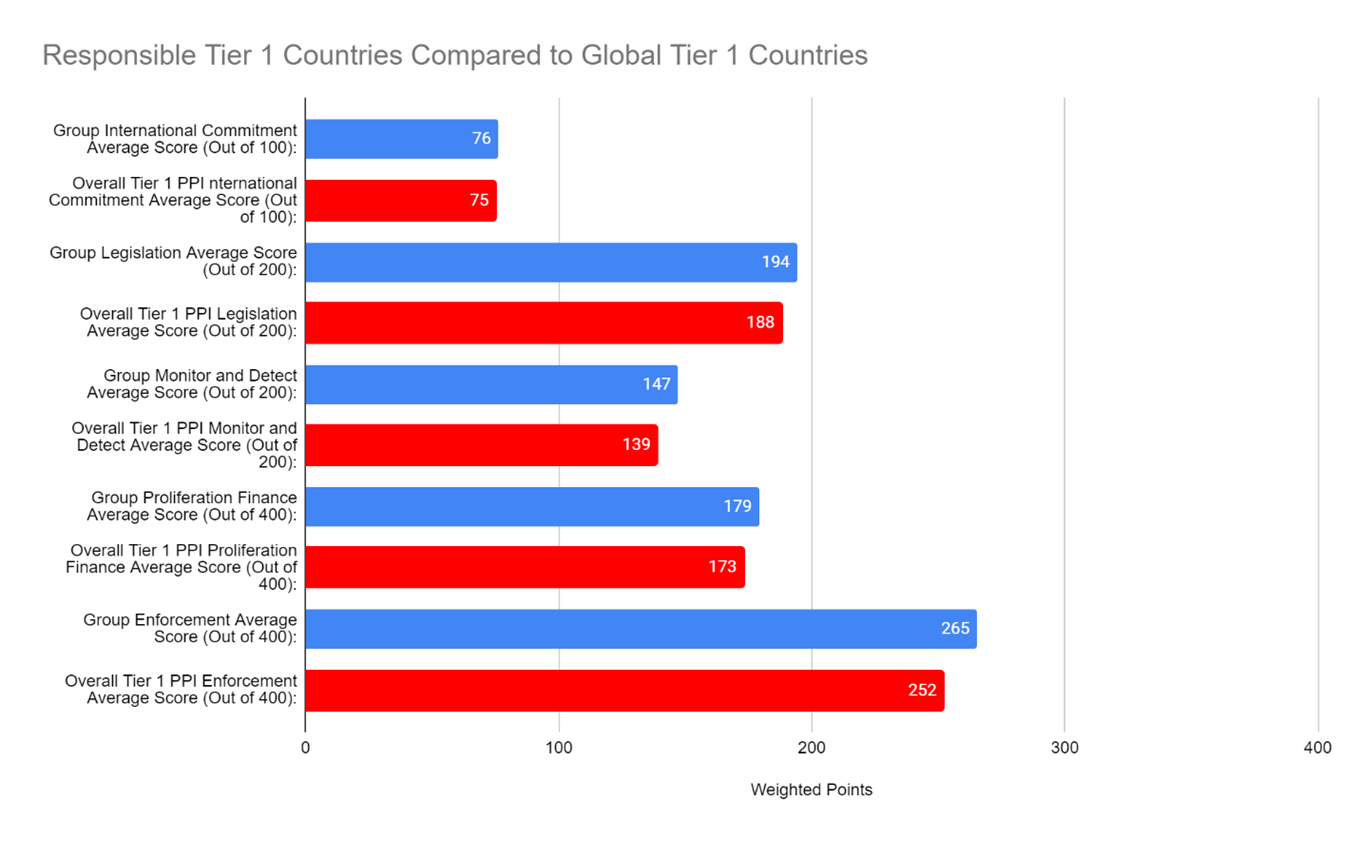

With these problematic countries removed, Figures 3 and 4 show this subgroup of twenty Tier 1 countries outscore on average the Tier 1 group. They not only overperform the overall Tier 1 average scores but also outperform in every super criterion.

Figure 3. The average PPI score for the subgroup of responsible Tier 1 countries compared to the global Tier 1 countries PPI average score, where the subgroup contains the all the Tier 1 countries identified in this study, excluding Iran, North Korea, and Belarus.

Figure 4. The subgroup of responsible Tier 1 countries compared to the overall average scores for all global Tier 1 countries for each super criterion area.

PPI Scoring vs Russian Transshipment Countries Identified by BIS

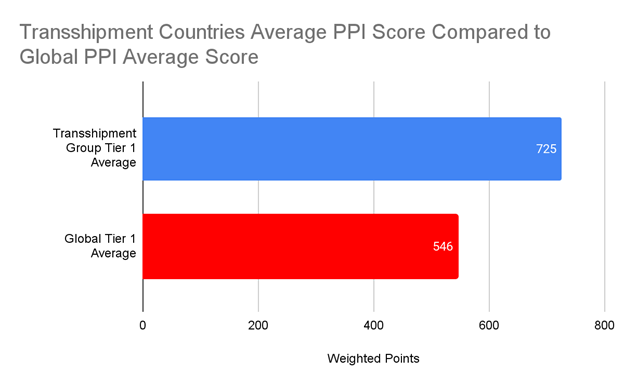

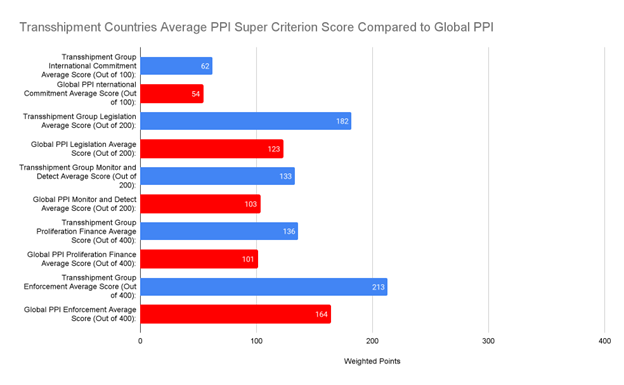

Another important subgroup includes the 17 countries identified by the BIS as common transshipment points for goods destined for Russia or Belarus. These seventeen countries outperformed the global averages in all five super criteria, including the overall PPI average (see Figures 5 and 6). Ten countries in this group are considered Tier 1, while the rest are Tier 2.

The ten Tier 1 countries in this BIS-subgroup have an average score of 740, and all belong to the subgroup of 20 countries identified above as responsible Tier 1 countries. However, the average of these ten countries is 121 points lower than the average of all 20 countries. This means that they, with two exceptions, fall in the bottom half of distribution of scores of this larger group of 20 countries.

The seven Tier 2 countries in the BIS list have an average score of 704, somewhat below the average of all 31 countries listed in Table 1 (728). Those countries scoring above 704 are Singapore, United Arab Emirates, Armenia, and Georgia.

China, Brazil, India, Turkey, Uzbekistan, Armenia, and Nicaragua all received less than half the maximum points in Super Criterion Adequacy of Enforcement, compared to their relatively high average score in Super Criterion Legislation, reflecting a discrepancy between the ability to pass laws and the ability or desire to enforce them. Kyrgyzstan is also included in this group due to failure to adjust its controls to compensate for its membership in the Russian customs union.

Figure 5. The average PPI score for transshipment countries compared to the global PPI average score.

Figure 6. The average PPI score for each super criterion for transshipment countries compared to the global PPI average score.

PPI Scoring vs Supplying Munitions and Combat Equipment

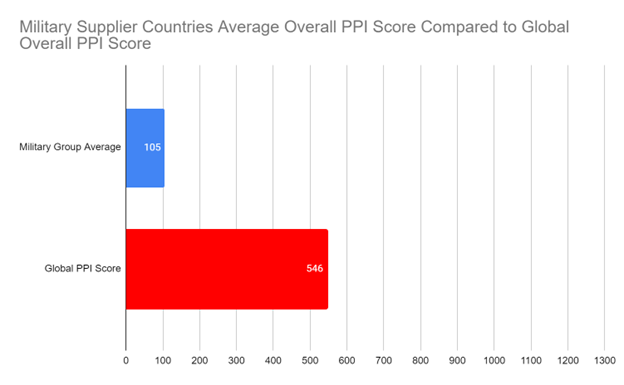

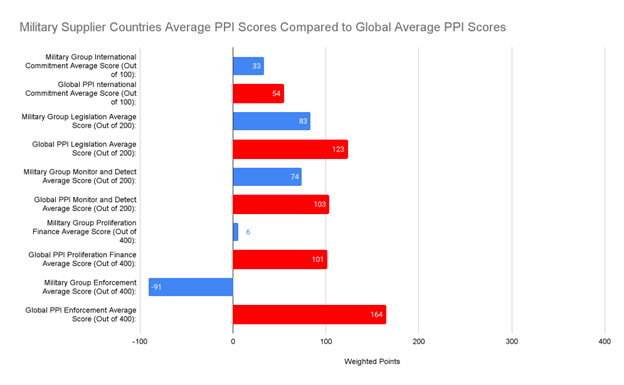

As expected, group 4, composed of four countries that have supplied Russia with munitions and military equipment for use in its war in Ukraine, performed poorly in the PPI. As seen in Figures 7 and 8, these countries have appalling performance in the PPI, and even received an average negative group score for Super Criterion Enforcement of -91 out of 400 points. No country received a positive score for enforcement, with Syria performing the worst. The negative scores reflect the unwillingness of these states to enforce international sanctions and their willingness to allow illicit and restricted items to originate or flow through their territory.

Figure 7. The average PPI score for the group of countries that supplied military equipment to Russia compared to the global PPI average score.

Figure 8. The average PPI scores for the group of countries that provided military equipment to Russia, compared to the global average PPI scores for each super criterion area.

Findings and Recommendations

The patterns in the scores of the 31 countries assessed here lead to several findings and recommendations to better counter Russia’s and its allies’ efforts to procure goods illegally.

Role of High-Scoring Countries

The situation with Russia demonstrates that even countries with strong strategic trade control systems have vulnerabilities when new threats arise. At the same time, Russia’s widespread dependency on many of the supplier countries’ products was unexpected and creates additional urgency and opportunity for the West and its allies to act. The relatively high PPI scores in the 31 countries, and particularly among responsible Tier 1 countries, signify that reforms in most of these countries will be easier to implement and can spread more easily to other high scoring countries not considered here. Collectively, these countries are well positioned to counter Russia’s efforts to violate export control laws, regulations, and norms. Their general regulatory environment concerning strategic commodities is strong, and the countries are strongly committed to export controls. As such, many of these countries can be expected to continue working diligently to recalibrate their approach to Russian trade in terms of more listed strategic goods, expanded enforcement, better end user and end-use checks, more scrutiny and enforcement of illegal financial arrangements used by Russia, its oligarchs, and its agents, enhanced international cooperation, and intelligence sharing about illicit networks and goods. But the situation demands more.

A key strategy to build international coalitions has been focusing on multilateral institutions able to create pressure and binding international sanctions. However, building coalitions today is complicated by the fact that Russia, as a veto-wielding power on the United Nations (UN) Security Council and a member of the consensus-ruled Nuclear Suppliers Group and other multilateral control regimes, is obstructing actions that could be taken by these bodies. It has prevented the imposition of UN sanctions for the invasion of Ukraine and can block the additions of items or procedures in the control regimes. The competing interests between Russia’s desire to prolong and win its war in Ukraine and the efforts to limit Russia and other states’ capabilities complicates finding a multilateral solution. Nonetheless, countries can take unilateral and collective action to implement and enforce their own sanctions outside of the purview of the UN. Efforts like these can and have proven effective and enable countries to target Russia and its smuggling networks. In building coalitions to thwart Russia, states should look for allies among responsible members of multinational export control regimes. In addition, like-minded and capable states can be drawn from the collection of all countries with an average PPI score close to or above the Tier 1 average. These groupings of like-minded states control much of the world’s advanced manufacturing capabilities, while having the world’s best export control systems.

Many goods important to Russia’s military programs have not been on national control lists and thus only require export licenses based on the restricted end-use and end user, which is often unknown or hidden by resales and third parties, as well as by the tactics used by Russian procurement networks. Adding new items to national lists is being done and more countries should do so. Such actions should be accompanied by enhanced end-use and end user checks. The United States has been spearheading its own effort to expand its national control list of dual-use items with additional dual-use items and technologies banned or controlled for Russia or use in Russia. So have the European Union (EU) and other U.S. allies.

As of today, a substantial group of countries have aligned with these additional export controls and sanctions on Russia. Countries that have so far committed to implementing “substantially similar export controls on Russia and Belarus, under their domestic laws” as the U.S. has, are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, and United Kingdom. 6 The U.S. and its like-minded partners should continue this effort to get additional countries on board and update the lists of restricted items swiftly as more information on items sought and used by Russia comes to light.

This list of countries aligning with the United States does not include any BIS-listed transshipment countries except Taiwan (Group 1 above) or any of the four countries supplying arms to Russia (Group 4). All countries in Group 2 and 3 (additional transshipment countries and dual-use suppliers) are on this list and are high scoring, with scores above the average of the 20 responsible Tier 1 countries discussed earlier. The Group 1 countries not on this list, with the exception of Israel, scored below the average of the 20 Tier 1 countries.

Strong government/industry cooperation has been critical to strategic trade controls strategies for over two decades. The current situation with Russia, with far more goods needed by its militaries, demands that far more industries participate in this cooperation and many more countries join. A priority for governments is identifying and recruiting companies with significant supply capabilities of dual-use items banned for Russia and Belarus, or other dual-use items that are not listed but could make a significant contribution to Russia’s military capabilities. At the same time, more assistance from governments is needed, as many of the new companies lack internal compliance programs (ICPs) or the resources to establish due diligence capabilities about the risks posed by their goods. A useful model for improving the capabilities of companies to spot suspicious inquiries is that charted by Germany and Britain, both of which routinely provide their domestic companies with detailed information about which companies and entities to avoid due to export control concerns and which goods traffickers could be pursuing. More countries should share detailed, current information with their companies and entities. Countries should more broadly use so-called “grey lists” of suspect companies and entities as part of advising supplier companies on suspect diversion points. High-scoring countries should aid in building these capabilities and resources in other states.

More Problematic Countries

Several countries’ relationship to Russia (or resistance to U.S. initiatives) may be coloring their enforcement of their own trade control systems. Several of these countries, such as Turkey, Brazil, China, and India, score more than a hundred points below the Tier 1 average, compounding the problem these countries pose to disrupting Russia’s efforts to outfit its military. Outreach to these countries should continue and pressure strategies evaluated and developed, such as temporarily suspending the implementation of bilateral or regional customs and trade facilitation measures or discussions on such.

Several other countries, including Iran, North Korea, Syria, and Belarus, are actively and willingly providing weapons and material support for Russia’s war in Ukraine. These countries are serial violators of international treaties and sanctions regimes. They deserve to have additional sanctions imposed on them for their activities with Russia. In addition, the European Union and the United States have an obligation to ensure that the missile embargo on Iran, regularly violated by Iran via drone shipments to Russia, is not lifted in October 2023, the date scheduled in UN Security Council resolution 2231.

Vigilance is required to prevent this list of arms suppliers from growing. It is important to prevent other states from supplying arms to Russia, where indicators could include voting in favor of Russia at the UNSC, ranking low in the PPI, and being widely sanctioned or under military embargo, such as Cuba or Venezuela.

Greater Enforcement

Efforts to combat the flow of illicit goods to Russia need to be supplemented by stronger enforcement actions from a range of supplier states. The European Union, among others, should devote greater resources and commitment to prosecute those bad actors that take advantage of the currently weaker prosecutorial environment in many EU countries and elsewhere. For example, Germany has recently advocated for better EU harmonization of criminal penalties applied for the falsification of end user statements. Germany is also one country where media reports indicate that arrests, raids, and investigations related to sanctions on Russia have increased in recent months, indicating that it is not only stepping up the enforcement but also the public messaging about it.7

Extraterritorial Enforcement

The United States should expand its use of extraterritorial enforcement actions, where it seeks the extradition of traffickers in other countries or seizes their financial assets even when held in non-U.S. banks. Allies should be encouraged to modify their laws as necessary and start their own extraterritorial enforcement actions. Several countries, including the United Kingdom and South Korea actively seek extraditions from other countries and the formation of bilateral extradition agreements, but more should do so, and more countries should enter the bilateral agreements sought by these states. Currently, about two-thirds of all countries have a bilateral extradition agreement with either the U.S. or the U.K. in place.8 For those countries unwilling to enter into a bilateral agreement, they should ensure that their national legislation would allow for extradition. Thus, at a minimum, countries should be encouraged to cooperate with the United States in specific instances so that suspects illegally aiding Russia can be arrested when traveling to sympathetic countries, and the U.S. can successfully extradite them to face charges.

Transshipment Countries

Perhaps the most immediate challenge posed by Russia‘s illicit trade activities involves transshipment. Many important goods are not being shipped directly to Russia but through intermediaries, as demonstrated by the BIS identification of 17 countries. Several approaches are being developed in this area, but more will likely be necessary. A few European examples illustrate their thrust and limitations.

EU 11th Sanctions Package. On June 21, 2023, the EU adopted another sanctions package that included a much greater focus on blocking transshipment or circumvention via third countries.9 The European Union, which Russia often targets, has prioritized preventing the diversion of restricted goods via third countries, but the requirement for consensus among all of its members proved challenging, resulting in the dilution of several of the remedies in the package.

Nonetheless, the package contains many important reforms. It applies sanctions not only to entities in Russia but also to entities in third countries, including China, Uzbekistan, the United Arab Emirates, Syria, and Armenia. 10 In total, the EU added 87 companies to its growing list of those enabling the Russian military and industrial complex in its war against Ukraine, as well as expanding the list of restricted goods that could technologically enhance Russia’s defense and security sector.

The package also established a stepwise increase in actions to stop circumvention. It first mandates further bilateral and multilateral cooperation with third countries and the provision of assistance to them. If cooperation does not yield results, the EU will target with sanctions third-party country operators which are facilitating circumvention and engage in dialogue with the third country. The last steps taken in case “circumvention remains substantial and systemic” are called “last resort measures.” At this point, “the Council may unanimously decide to restrict the sale, supply, transfer or export of goods and technology whose export to Russia is already prohibited – notably battlefield products and technologies - to third countries whose jurisdiction is demonstrated to be at a continuing and particularly high risk of being used for circumvention.”

Given the nature of such stepwise proposals, working through the steps for a particular country could take significant time, moving far slower than Russia’s counter diversion moves. Delays could be compounded since the package does not appear to have a timeline for compliance at each step. Making the situation more challenging, the “last resort measures” are not mandated; their imposition apparently could be blocked by one wayward EU Council member.

The 11th sanctions package targets another loophole for companies selling intellectual property rights to Russia that has become more glaring following the post-invasion export bans. This loophole allows Russia to make restricted goods in Russia or in a third country using purchased supplier country technology. It is not clear if efforts are also made to prevent the sale of sensitive intellectual property to companies located in certain third countries; if not, this could present a new loophole unless the third country aligns their export bans with those of the EU.

The 11th package of measures also targeted an unexpected loophole—Russia exploiting its geographic position as a transit country. Strategically located between Europe and Asia, Russia has been serving as an important transit point of goods transported from the EU to third countries by rail or by road. However, to ensure that items restricted for Russia do not illegally stay in Russia while declared to be just passing through, Russia should not be used as a transit country for restricted items going forward. In line with this, the EU is banning the use of Russia as transit route for items restricted for Russia. Other countries should be on the lookout for this loophole and block it. This will require additional customer due diligence, greater scrutiny of end user statements, and third-country cooperation.

**German Initiatives. ** The German government earlier this year published a list of ten steps governments and companies can take to this effect. 11 Sanctioning entities complicit in diversion, not only those in Russia but also those in third countries, is one of the main steps.

Additional steps Germany proposed include placing more due diligence requirements on EU exporters when exporting items to third countries that are not on the EU dual-use list but are banned for Russia, including items on a list of so-called Advanced Technologies. These lists are updated on a regular basis, most recently under the EU’s 11th sanctions package. The proposal states that in Germany, end-user statements will be required for these goods’ customs declarations if they are intended for “certain” third countries. The proposal does not list those countries, and its publication would be useful. Germany further proposes placing additional responsibility on the public by making it mandatory to notify authorities when a member of the public becomes aware of Russia-related sanctions evasion activities or related information.

Germany has also proposed establishing an EU list of third-country companies or entities that, while not sanctioned, would be banned from receiving goods banned for Russia. Media citations of diplomats involved in the passing of the 11th sanctions package state that additional Chinese entities were taken off the sanctions list at the last minute. 12 These companies could be good candidates for inclusion on such a list.

Germany could also apply to the Russian situation a procedure it applies to the UAE, another country with great transshipment volume and concern. Germany has instituted a system to obtain higher confidence that licensed items are not diverted via the UAE; it has a bilateral agreement with the UAE whereby the UAE must approve, i.e., stamp, the end-user statement for any UAE end-user of a licensed item from Germany before the item can be shipped. Not only Germany but other concerned states could apply a similar procedure to sensitive or restricted exports to states which pose a significant risk that goods could be transshipped to Russia.

Designate a Country of Diversion Concern. The German actions and the new EU stepwise circumvention response in the 11th package represent important progress against transshipment to Russia. But the EU process is ponderous and uncertain to be successful, particularly in the short term. There is another approach that is easier to implement and more likely to achieve success in the short term.

For countries of transshipment concern continuing to allow or tolerate diversions of sensitive goods to Russia, major supplier governments should promptly issue draft regulations when to designate those countries as “destinations of diversion concern.” Such a designation would trigger far greater scrutiny of a wide range of exports, not just sensitive ones, to that country, providing an incentive for the country to rapidly improve its ability to provide assurance that transshipment of items prohibited for Russia will not occur. The logic is simple—if the transshipment country will not act, then the supplier country must.

Such an approach was previously used successfully by the U.S. Commerce Department in the 2000s against transshipment countries or “hubs” used by the A.Q Khan network that lacked strategic export control laws, and the regulation did not even need to be formalized because the targeted countries created strategic trade control systems. 13 Countries should apply a similar approach against those not willing to stop transshipments of sensitive goods to Russia.

A country’s draft regulation should be supplemented with diplomatic outreach, offers of strengthened bilateral and multilateral cooperation, and expanded export control technical assistance to the potential country of diversion concern. However, it should quickly become apparent which countries are willing to take the necessary steps to ensure transshipment through them is being curtailed and the companies punished.

The originally published Commerce Department draft criteria, slightly modified, are still applicable today in helping make a determination of a country’s status as a destination of diversion concern:

- Transit and transshipment volume;

- Inadequate export/reexport controls (the PPI can be useful here);

- Demonstrated inability or unwillingness to control diversion activities to Russia;

- Government not directly involved in diversion activities; and

- Government unwilling or unable to cooperate with the exporting government on enforcement or interdiction efforts.

Once a supplier country determines a country is of diversion concern, that country would face a series of additional requirements to ensure transshipments do not occur, such as significantly more goods, beyond just sensitive ones, becoming subject to a license, more scrutiny of license applications, fewer licensing exemptions, more conditions on licenses, and more thorough end-use and end user checks.

Fear of being designated a country of diversion concern should encourage several resistant or laggard transshipment countries to develop credible methods of detecting and preventing banned retransfers of goods to Russia and encourage the importer to show due diligence and ensure compliance with regulations such as Germany’s proposed end user statement requirement. Otherwise, the country may face severe delays in importing a wide range of goods, including many not previously subject to export licensing or scrutiny.

Guidance to Individual Suppliers

Individual suppliers need to exercise caution in selling goods today for fear of them ending up in Russia, given Russia’s extensive use of illicit trade networks and its exploitation of a wide variety of transshipment hubs. Table 2 lists the 31 countries considered in this report, color-coded as to their actions to thwart Russia obtaining sensitive goods, their risk of transshipment, or their complicity in providing military goods to Russia. The first group (color coded green) constitutes those high-scoring countries that are known publicly to be working together to counter Russia’s illegal trade. The second group (blue) has demonstrated that they pose a transshipment risk. Suppliers should exercise caution when selling goods to these countries and seek greater assurance that their goods are not transshipped to Russia. The third group (yellow) constitutes countries that have lax enforcement records and pose a greater transshipment risk than the blue-colored group. Suppliers should exercise greater caution with these countries. The fourth group (red) are countries that are actively helping Russia’s military; suppliers should exercise extreme caution and ban sales to these countries. These color codes are also described in a legend after Table 1.

One implication of the color coding, not discussed in the above sections, is that it should be a priority for countries in the green category to take steps, collectively and individually, to convince countries in the blue category to move into the green one. More pressure should be applied to those countries in the yellow group to desist allowing transshipments to Russia as well as their direct supply of Russia with restricted goods.

It should be noted that the color coding correlates with the 31 countries’ PPI score. For a country not considered in this report, its PPI score can provide a first indication of how to evaluate its risk with regards to Russia.

Table 2. PPI Score of 31 Countries with Risk, Actions

Last Word

The vast majority of countries have a vested interest in halting the flow of strategic commodities to Russia critical to its aggressive and illegal war effort. This study shows that there is much work to do to thwart Russia, but the mature trade control systems in many like-minded states provide a sound basis to create tools to act effectively against this new Russian threat to the system of international trade and security. At the same time, these like-minded countries can press countries with inadequate strategic export controls systems to both improve them and participate more actively in thwarting Russia’s illicit trade.

1. David Albright, Sarah Burkhard, Spencer Faragasso, and Linda Keenan, Peddling Peril Index for 2021/2022 (Washington, D.C.: Institute for Science and International Security, 2021), https://isis-online.org/ppi/detail/peddling-peril-index-for-2021-2022/. ↩

2. “FIN-2022-Alert003: FinCEN and the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security Urge Increased Vigilance for Potential Russian and Belarusian Export Control Evasion Attempts,” United States Bureau of Industry and Security, June 28, 2022, https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/2022-06/FinCEN%20and%20Bis%20Joint%20Alert%20FINAL.pdf. ↩

3. After it was listed by BIS, Taiwan took action to align their lists of items restricted for Russia and Belarus with the U.S. lists, see footnote 6. ↩

4. Hong Kong is also noted as a transshipment country by some sources, but for export controls Hong Kong can no longer be treated differently than China. ↩

5. Financial sanctions evasion hubs, for example, Cyprus, are not included. An “*” Indicates an NSG member. ↩

6. U.S. Code of Federal Regulations, “Supplement No. 3 to Part 746—Countries Excluded from Certain License Requirements of §§ 746.6, 746.7, and 746.8,” https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-15/subtitle-B/chapter-VII/subchapter-C/part-746/appendix-Supplement%20No.%203%20to%20Part%20746. ↩

7. “Germany takes a tougher stance against bypassing Russia Sanctions via third countries,” JD Supra, February 28, 2023, https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/germany-takes-a-tougher-stance-against-5586959/. ↩

8. Peddling Peril Index for 2021/2022. ↩

9. European Council, “Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine: EU adopts 11th package of economic and individual sanctions,” Press Release, June 23, 2023, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/06/23/russia-s-war-of-aggression-against-ukraine-eu-adopts-11th-package-of-economic-and-individual-sanctions/. ↩

10. Jorge Liboreiro and Efi Koutsokosta, “EU agrees new sanctions against Russia, targeting Chinese companies suspected of circumvention,” Euronews, June 21, 2023, https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2023/06/21/eu-agrees-new-sanctions-against-russia-targeting-companies-suspected-of-circumvention. ↩

11. The list was published by the German Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action and is available in German at https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Downloads/V/vorschlage-zur-effektiveren-bekampfung-der-sanktionsumgehung.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=1. ↩

12. Jorge Liboreiro and Efi Koutsokosta, “EU agrees new sanctions against Russia, targeting Chinese companies suspected of circumvention,” Euronews, June 21, 2023, https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2023/06/21/eu-agrees-new-sanctions-against-russia-targeting-companies-suspected-of-circumvention. ↩

13.“Country Group C; Destination of Diversion Concern,” Draft Regulation, Bureau of Industry and Security, Department of Commerce, Federal Register, Vol. 72. No. 37, February 26, 2007. ↩

twitter

twitter