Reports

52 Countries Involved in Violating UNSC Resolutions on North Korea throughout most of 2017

by David Albright, Sarah Burkhard, Allison Lach, and Andrea Stricker

March 9, 2018

Lede and Summary

The failures of countries to act, or their willful complicity in North Korean schemes, account for a tally of 52 states found by the Institute in this report to be engaging in United Nations Security Council (UNSC) sanctions violations from the period January to September 2017.1 North Korea continues to operate extensive illicit trade and financial networks around the world. At times those networks are supported with the knowledge of states, or North Korea’s efforts are detected, but are not shut down in a timely manner. There is no excuse for the behavior of complicit, on-going violators.

The information on violations is compiled from a report of the UNSC Resolution 1718 (2006) Sanctions Committee on North Korea and its Panel of Experts appointed pursuant to Resolution 1874 (2009). The Panel of Experts issues biannual reports on North Korea’s compliance with the resolutions. The Institute obtained and reviewed a copy of the Panel of Experts’ most recent report, dated January 2018. The report has not yet been approved for release by the Security Council, likely due to political sensitivities. The Institute urges Security Council members to agree to the adoption and public release of the Panel of Experts report without further delay.

It should be noted that the number of violators has increased since a December 2017 Institute report, from 49 during the time period March 2014 to January 2017, to 52 countries from January to September 2017. Despite the increase in the total number, which on the surface is alarming, the Institute views this as an indicator of stronger enforcement efforts by member states and better reporting of violations. The implementation of additional sanctions may also require time for countries to adjust. On balance, the process is identifying violators more systematically and completely, which in turn points to ways to better apply additional political pressure to stop further violations and punish those who persistently violate sanctions.

Using the data of a separate Institute study, the Peddling Peril Index (PPI) for 2017, which ranks 200 countries and entities according to their efforts at preventing trafficking in strategic commodities and the effectiveness of their export control systems, we draw out additional findings aimed at stopping sanctions’ violations involving North Korea. One is that states with poor export controls or high levels of corruption are more prone to being targeted by North Korea and violating UN sanctions. By identifying classes of states more prone to violations via the PPI, more effective countermeasures can be developed.

Pending the achievement of concrete progress on North Korean denuclearization, the United States is expected to enforce and likely increase sanctions against North Korea and seek more effective implementation of those sanctions and associated export control laws globally. The Institute supports such an approach and believes that sanctions should be reduced only when North Korea demonstrates concrete progress on denuclearization. In addition, any North Korean denuclearization settlement should include North Korea ending its illicit procurement and financial practices and the development of a responsible, internationally accepted export control system that includes bans on the proliferation of dangerous goods and services.

Key Findings

52 countries are assessed as violating UNSC sanctions on North Korea during the time period January to September 2017, compared to 49 during the time period March 2014 to January 2017.

Nine countries were found to be involved in military-related sanctions violations.

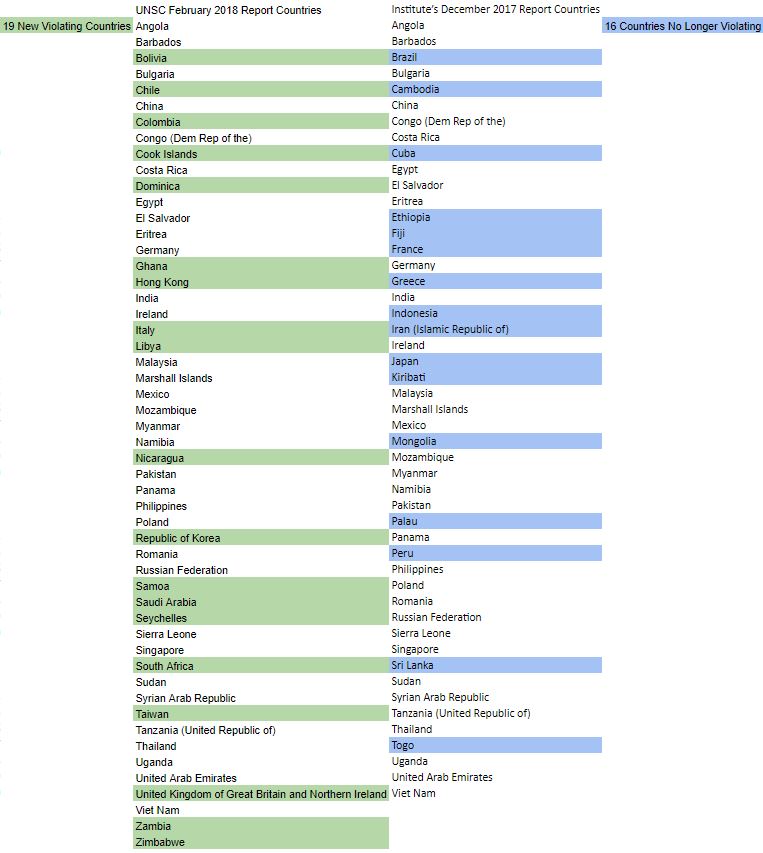

Of the 49 countries previously identified in the December report, 16 are no longer violating sanctions, according to the latest Panel of Experts report. However, there are 18 new violating countries, suggesting North Korea is able to find new partners willing to skirt sanctions despite others’ decision to no longer do so (see Table 1).

There are instances in which some violation categories dropped significantly; new sanctions categories were included due to the passage of additional UNSC resolutions.

North Korea targeted 19 countries as unwitting middlemen or transit points to exploit and further its procurement or trading schemes (an increase from 13 in the previous reporting period).

Nineteen countries listed as involved in non-military-related sanctions violations, including financial violations, differ from the 19 countries listed in the Institute’s December 2017 report. This suggests that North Korea is having to look elsewhere to facilitate the transfers of funds into the country. Most notably, China is not listed as a financial enabler as it has been in the past.

Twenty countries (up from 18) were involved in imports of sanctioned goods and minerals from North Korea. The countries differ from those in the previous report, suggesting North Korea has had to find new trading partnerships.

The upticks in figures in a relatively short time period suggests that member states are exercising greater vigilance and enforcement efforts, while North Korea continues its efforts to subvert sanctions. Some countries have not yet come into compliance with the new UN sanctions restrictions (or willfully violate them), and the widening net of sanctions that have been implemented throughout 2017 is catching additional bad actors.

In addition to continuing the push for new sanctions to minimize North Korea’s ability to outfit its destabilizing programs, it is vital to push UN member states for full implementation of current sanctions. The natural group to press to fully implement sanctions and stop cooperation with North Korea includes the 52 countries identified as being complicit in various forms of alleged or proven violations of sanctions resolutions.

The creation of punitive measures is an effective means to accelerate more compliant behavior in the short term. The Panel of Experts previously reported that Uganda took some measures to halt its military cooperation with North Korea following international attention and pressure. According to the most recent UN report, Angola has taken further steps to end its employment of and cooperation with designated individuals and entities but has not yet fully addressed the status of a North Korean military advisory mission that was reported by a UN member state to be present in the country up until January 2017.

Using the findings of the Peddling Peril Index for 2017, we determined that in pursuing its banned or illegal activities, North Korea often cooperates with or otherwise exploits countries with weak or nonexistent export and proliferation financing controls and those that suffer on average from more corruption than other countries. Countries should watch carefully for illicit trade involving North Korean entities that are potentially disguised behind entities located in highly corrupt countries.

Many of the 52 countries scored poorly overall on the Peddling Peril Index, reinforcing the view that countries that do poorly on the PPI are targets of North Korea. The PPI’s analytical framework combined with extensive data allows the drawing out of other significant findings about the set of 52 countries associated with sanctions violations, such as that states with poor export controls or high levels of corruption are more prone to being targeted by North Korea and violating UN sanctions.

All countries should implement effective export controls. Given that more than 50 percent of UN member states are judged in the PPI as not having sufficient export control legislation in general, and about 25 percent barely have or do not have export control laws, this recommendation is critical. Especially for the countries identified in this report as having barely any or no relevant legislation, they should establish strategic export control laws that include bans on sanctioned trade with North Korea and other pariah states, as the Panel also recommends.

Countries that have violated the UNSC resolutions with respect to proliferation or other banned financing should be pressed to turn to the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), its regional bodies and guidelines, and specifically ask for assistance in implementing FATF recommendation 7 as laid out in its updated 2012 framework. This recommendation states: “Countries should implement targeted financial sanctions to comply with United Nations Security Council resolutions relating to the prevention, suppression and disruption of proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and its financing. These resolutions require countries to freeze without delay the funds or other assets of, and to ensure that no funds and other assets are made available, directly or indirectly, to or for the benefit of, any person or entity designated by, or under the authority of, the United Nations Security Council under Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations.”2

Countries that inadvertently imported large quantities of minerals or ore or other controlled goods from North Korea should increase physical inspections of incoming shipments, especially ships under Flags of Convenience or other flags that have previously been used by North Korea.

Countries that have provided shipment assistance to North Korea should re-evaluate such practices and, if violations exist, ban North Korea’s access to their flags and registries.

The UN Security Council and major countries should accelerate the designation of individuals and entities, including banks that do business with North Korea, that violate UNSC resolutions on North Korea.

In order to have an impact on North Korea’s calculations regarding its destabilizing and threatening nuclear, missile, and military programs, countries should end their non-humanitarian-essential trade with North Korea. Countries should be urged to expel North Korean military personnel and suspend any further military cooperation or pressed not to undertake further military cooperation of any kind. Remittances from North Korean workers should be stopped from going to North Korea, and countries should reduce numbers of North Korean “guest workers.”

Introduction

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) has recently and markedly increased the pace with which it passes new sanctions resolutions on North Korea, while also increasing the breadth and depth of those sanctions to target more commodities imported and exported by North Korea. These sanctions aim to stop vital revenue streams which support the augmentation and maintenance of North Korea’s nuclear, missile, and military programs. Since November 2016, the Security Council has passed five resolutions (UNSCRs 2321 (December 2017), 2356 (September 2017), 2371 (August 2017), 2375 (June 2017), and 2397 (November 2016))3 targeting not only people and entities associated with North Korea’s most destabilizing military programs, but also a range of commodities that act as their monetary sources of funding and means of operations, such as imports by North Korea of petroleum products and natural gas, its imports and exports of coal and iron ore, and even its exports of textiles and seafood. These sanctions are meant to restrict the ability of North Korea to expand and refine its nuclear, missile, and military programs, and to penalize it for its activities.

The United States has spearheaded the passage of new UNSC sanctions resolutions and has committed along with its allies to continue strengthening unilateral sanctions to supplement them until North Korea reverses course. In mid-February, the United States announced a new set of unilateral sanctions. U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley warned, “We are ramping up the pressure on the North Korean regime, and we’re going to use every tool at our disposal, including working with our allies and through the U.N., to increase the pressure until North Korea reverses course.”4 Until concrete progress toward North Korean denuclearization is achieved, the United States is expected to, and should, enforce sanctions against North Korea and seek more effective implementation of those sanctions and associated export control laws.

In its efforts to further its nuclear, missile, and conventional military programs, North Korea seeks to undermine international sanctions and the export control laws of other countries. It has long attempted to find sympathetic governments or countries with weak or nonexistent export controls that will supply these programs or be more conducive to military and commercial cooperation. North Korea also targets states that are otherwise strong enforcers of export controls and uses deceptive methods, such as front companies or actors to bypass these countries’ export control laws. To better understand North Korea’s strategies and methods to defeat sanctions, the Institute collected and analyzed North Korea’s illicit procurement and trading activities as reported in United Nations Panel of Experts report, from January to September 2017.5 A total of 52 countries were found to be complicit in various forms of violations of UNSC sanctions resolutions on North Korea. Using the Peddling Peril Index, we also considered these 52 countries in terms of 1) their overall ranking in the index; and 2) the rigorousness of their export control legislation.

Military-Related Sanctions Busting

Nine governments (down from 13 in the previous Institute report) were found to be involved in military-related cases of North Korean sanctions violations, including: Angola, Egypt, Eritrea, Mozambique, Myanmar, Sudan, Syria, Tanzania and Uganda (the latter involving potentially on-going activities). In some cases, these mostly undemocratic regimes received military training from North Korea; in others, they received or exported military-related equipment to or from North Korea. North Korea allegedly tried to outfit Syria, via Chinese companies, with chemical weapons-relevant materials. The shipments were interdicted by UN member states. These included items sent between November and December 2016: “acid resistant tiles along with adhesive paste and accessories” which were determined to be “materials that can be used to build bricks for the interior walls of [a] chemical factory.” Other cargo included “valves, welded pipes (23 tons), stainless steel seamless pipes (27 tons) and cables.” This Panel finding indicates that North Korea may be complicit in the on-going genocide against civilians involving the use of chemical weapons by the Syrian Assad regime.

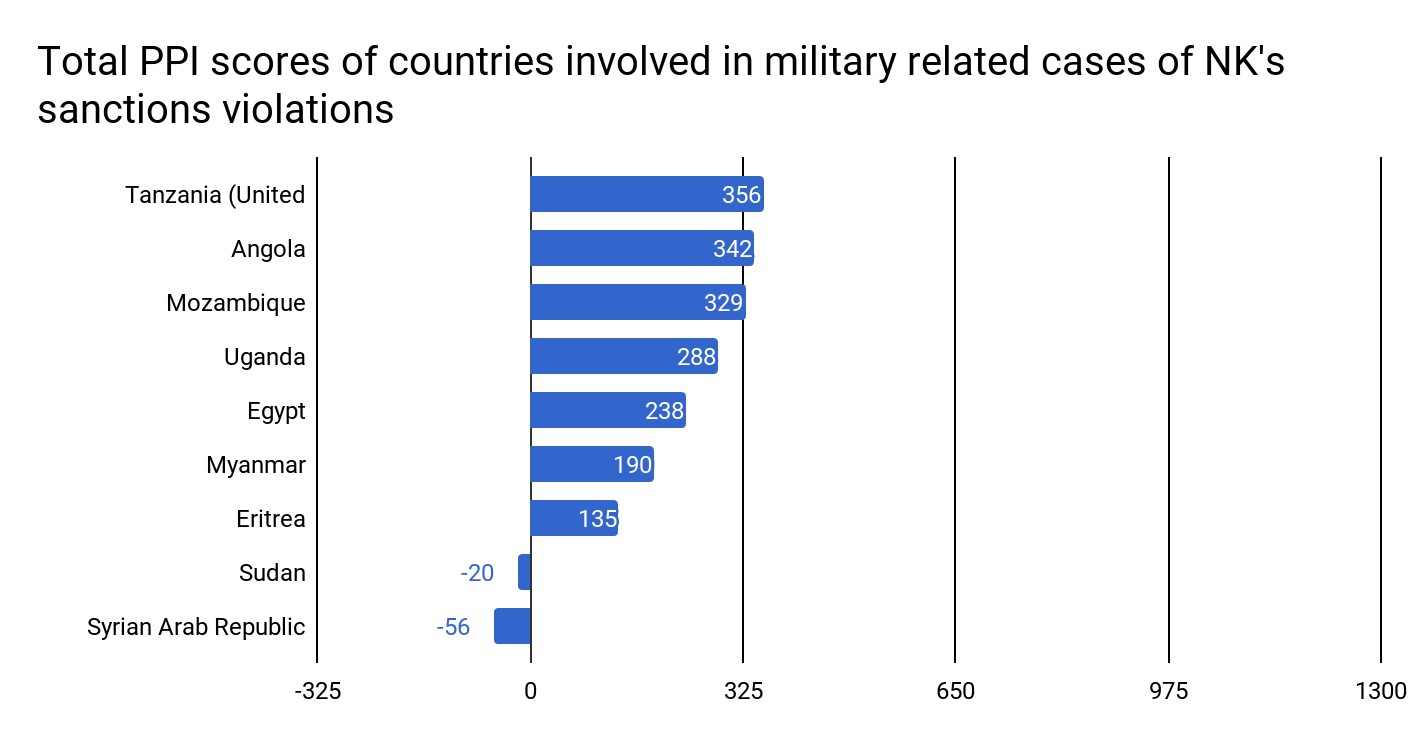

The overall scores of these 9 countries in the PPI are low. The mean for these countries is 200, down from 254 points out of 1,300 total points. A sufficient strategic export control system in the PPI typically would require a score of at least 650 points. The highest scoring country received only 27 percent of all possible points (355) (out of a possible 1,300), with two countries receiving negative scores. The PPI scores are shown in figure 1.

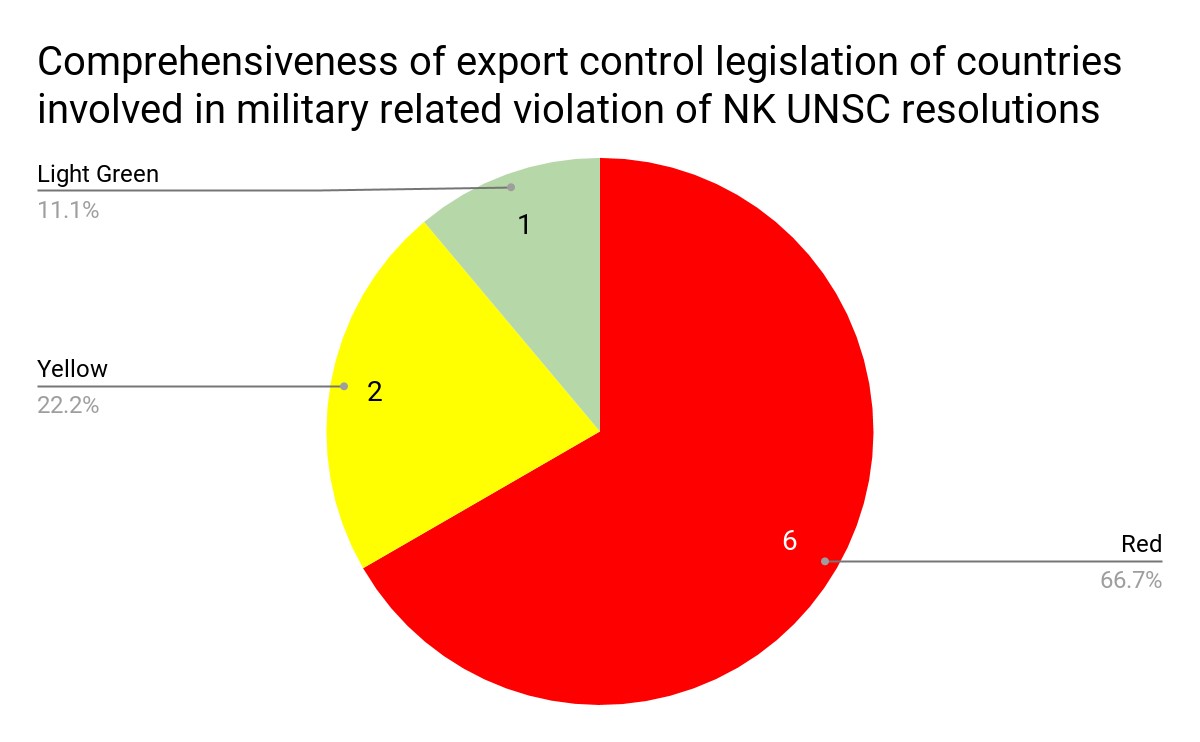

Eight of these 9 countries have inadequate export control legislation according to the PPI’s definitions (see below). This is shown in the pie chart in figure 2.

Legislative Categories in the PPI

In the PPI, countries are categorized into five levels of apparent comprehensiveness of their control lists as summarized below.

Dark Green (legislation is comprehensive): Export control legislation or agreements includes controls or clauses relating to nuclear direct-use and nuclear dual-use goods, (nuclear and nuclear-dual use commodity controls such as implementation of NSG Parts 1 & 2 or their equivalent), in addition to conventional weapons. The most commonly used lists are the EU Control List and Wassenaar Arrangement list.Light Green (legislation is somewhat comprehensive): Export control legislation or agreements includes controls or clauses relating to nuclear direct-use goods (nuclear commodity controls such as implementation of Nuclear Suppliers Group Part 1 list or an equivalent), in addition to conventional weapons.Yellow (legislation is deficient): These countries have comprehensive, overarching nuclear safety and security laws which place transfer controls on nuclear material and equipment. If the PPI team was unable to locate the relevant legislation, the 2016 Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI) Nuclear Security Index was consulted, specifically its data on whether a country has or does not have a national legal framework for the Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material (CPPNM). These countries are not viewed as having effective export control laws governing nuclear and nuclear-related commodities, but their existing legislation is viewed as better in a relevant export control sense than the legislation or lack of legislation in the red and orange categories.Orange (legislation has serious deficiencies): Export control legislation or agreements include only conventional weapons as laid out under the Arms Trade Treaty. These are not considered relevant export control legislation for the PPI.Red (legislation is non-existent or severely deficient): Export controls may include small arms and light weapons (SALW), and/or radioactive materials under environmental laws. These are not considered relevant export control legislation for the PPI.

Figure 1. All 9 countries received less than 50 percent of the possible 1,300 points. Six received less than 25 percent. The mean is 200 points out of 1,300 points.

Figure 2. Eight out of the 9 countries in this category have barely any or no export control legislation (red and yellow color designation). The legislation color key described qualitatively and in brief is: Dark Green- legislation is comprehensive; Light Green- legislation is somewhat comprehensive; Yellow- legislation is deficient; Orange- legislation has serious deficiencies; and Red- legislation is non-existent or severely deficient. See text for legislative categories.

High Corruption among these Nine Countries

Also noteworthy is that all of these nine countries do poorly on the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) by Transparency International, which ranks 176 countries on a scale from 1 to 176, where a ranking of 176 is most corrupt.6 The above nine countries have an average rank of 147 in the CPI. None of them ranks above 100. All except one country rank in the bottom third of the index.

Other Alleged Sanctions Violations

A range of countries were reported as involved in other violations of North Korean UNSC sanctions, as outlined below. These alleged and proven violations were organized into three broad areas, namely non-military-related cases, including financial violations; imports of sanctioned goods and minerals from North Korea; and shipping-related sanctions.

Nineteen countries were involved in non-military-related cases of sanctions violations that involved financial enabling, employment of North Korean nationals, travel violations, construction contracts, and allowing North Korea to use property for commercial purposes. These countries include: Angola, Bulgaria, Germany, Italy, Libya, Malaysia, Mozambique, Namibia,7 Pakistan, Poland, Romania, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Syria, United Arab Emirates, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. These 19 countries differ from the 19 countries listed in the Institute’s December 2017 report which suggests North Korea is having to look elsewhere to facilitate non-export-related financial inflows. Most notably, China is not listed as a financial enabler as it has been in the past.

Twenty countries (up from 18) were involved in imports of sanctioned goods and minerals from North Korea, including coal, copper ore, iron/steel, nickel, silver, and zinc. The countries importing these goods as reported to the Panel were: Barbados, Bolivia, Chile, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Ghana, India, Ireland, Malaysia, Mexico, Mozambique, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Philippines, Russia, South Korea, Thailand, and Vietnam. As with the non-military-related sanctions violations previously discussed, the countries differ from those in the previous report, suggesting North Korea has had to establish new trading partnerships. The largest number of incidents reported to the Panel is related to North Korean exports of iron/steel and coal. The two countries with the most incidents of importing from North Korea are Russia, followed by China.

To transport illicitly traded technologies, goods, and minerals to and from North Korea, North Korea often relies on receipt of shipping assistance from other countries. Twelve countries associated with re-flagging of vessels, transshipping North Korean coal, document falsification, petroleum transfer, ship-to-ship fuel transfer, and other shipping-related sanctions violations include: Cook Islands, Dominica, Hong Kong, Marshall Islands, Panama, Russia, Samoa, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Singapore, Taiwan, and the United Kingdom (incidents involving British Islands). This accounts for a reduction from the previous report which identified 20 countries, involved in extensive re-flagging-related sanctions violations. However, some of the re-flagging and shipping-related schemes identified by the Panel are egregious and complex, such as ship-to-ship transfers of banned cargo, turning off ship automatic identification systems in violation of international maritime conventions, changing ship identities mid-route by adapting new names, flags, and call signs, and taking evasive actions to try to hide the port where cargo is loaded onto the ship.

The UN report lists other sanctions violations that are not included in this analysis because the participation of the countries appears entirely inadvertent. The following 19 (up from 13) countries and territories were targeted by North Korea to further its trading schemes: Australia, Austria, China, Fiji, Hong Kong, Italy, Japan, Marshall Islands, Panama, Samoa, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Togo, Switzerland, Malaysia, Taiwan, the United Kingdom, and Vietnam. Panama, Sierra Leone, and Togo were inadvertently part of North Korea’s coal laundering scheme at the port of Kholmsk, as reported in the Washington Post.8

Taking Stock

In total, 52 countries were identified as involved in sanctions violations in one of the four areas discussed above. Some countries had multiple violations, although the total number for each country is not listed in this report. There was also turnover in terms of countries that violated UN sanctions. Of the 49 countries previously identified, 16 are no longer violating sanctions, according to the latest Panel of Experts report. However, there are 18 new violating countries, suggesting North Korea is able to find new partners willing to skirt sanctions despite others’ decision no longer do so (see Table 1).

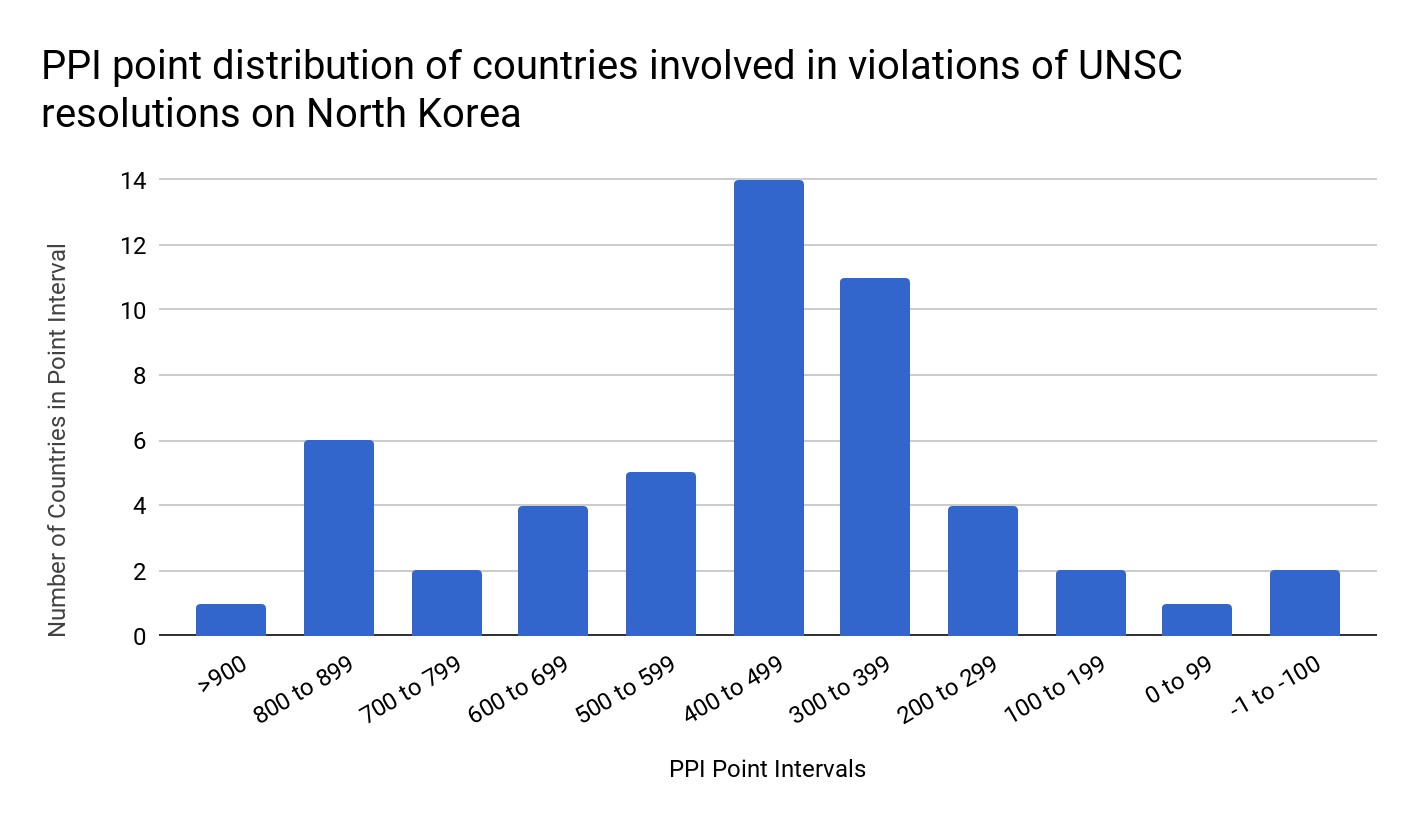

These 52 countries have a mean score in the Peddling Peril Index of 470 out of 1,300 points, again a relatively low average. Figure 3 shows the PPI score distribution, where there is a maximum peak in the 300 to 499-point intervals. This peak reflects that many of the countries involved in sanctions violations in general lack sufficient strategic export controls. Forty-two of the 52 countries scored fewer than 50 percent of the overall points assigned in the PPI, a mark of less than sufficient export controls, and 10 scored less than 25 percent. Moreover, it should be noted that there are many other countries that have received similar or lower PPI scores, making them potentially more vulnerable to North Korean exploitation.

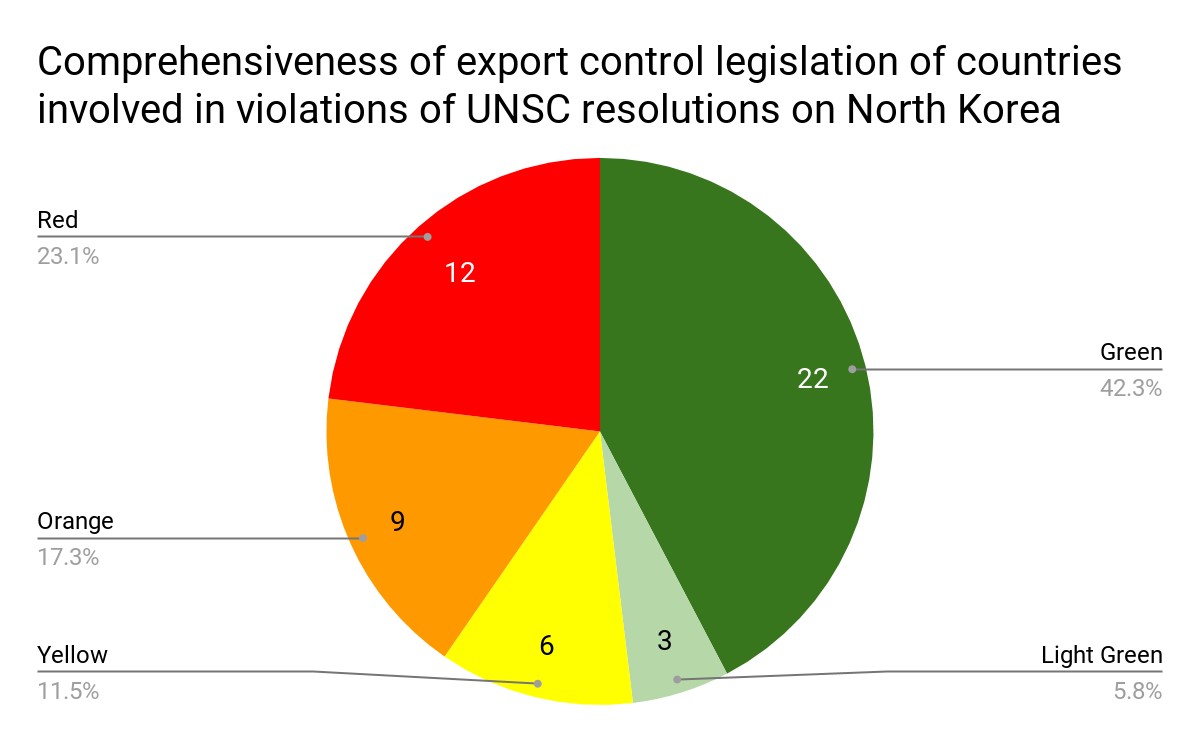

Half of the 52 countries that were involved in violating UNSC resolutions on North Korea have poor export control legislation, and many of the countries that do have sufficient legislation have a high degree of corruption relative to their peers, as measured by the CPI. Figure 4 shows that out of 52 countries, 27 have inadequate export control legislation, categorized as red, orange, or yellow colors.

In total, 25 countries out of the 52 involved in violations of UNSC resolutions on North Korea have green color-coded export control legislation, which means their legislation is judged as comprehensive. However, many of the 20 countries listed show a higher degree of corruption on the CPI compared to other dark green countries. Their average CPI rank is 86 out of 176, with a median of 87. For all green countries in the PPI, the average CPI rank is 68 and the median is 62.

Table 1. Countries that violated UNSC North Korean Sanctions Reported to UNSC Panel

Figure 3. Distribution of PPI scores for the 52 countries that were involved in violating UNSC sanctions on North Korea.

Figure 4. This pie chart shows the comprehensiveness of export control legislation of all 52 countries identified as involved in violations of UNSC sanctions resolutions on North Korea. Anything but green is considered inadequate legislation in the PPI. (This figure excludes 17 countries that were targeted by North Korea using illicit procurement schemes).

1. This Institute report constitutes an update to the Institute’s previous report on the subject, Countries Involved in Violating UNSC Resolutions on North Korea, released on December 5, 2017. That report catalogued all violations reported by the Panel of Experts from March 2014 to January 2017, finding that 49 countries were engaging in sanctions violations with North Korea.↩

2. 2012 FATF Recommendation 7: Targeted financial sanctions related to proliferation. See: http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/recommendations/pdfs/FATF_Recommendations.pdf↩

3. United Nations Security Council, Security Council Committee Established Pursuant to Resolution 1718 (2006): Resolutions, https://www.un.org/sc/suborg/en/sanctions/1718/resolutions?page=1↩

4. Michelle Nichols, “U.S. pushes more U.N. sanctions targeting North Korea oil, coal smuggling,” Reuters. February 23, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-north-korea-missiles/u-s-pushes-more-u-n-sanctions-targeting-north-korea-oil-coal-smuggling-idUKKCN1G72HA↩

5. Unpublished report of the UN Panel of Experts established pursuant to Resolution 1874 (2009), circa January 2018.↩

6. Transparency International, Corruption Perceptions Index 2016. There is a new CPI for 2017 but it is not used here in order to ensure the analysis is consistent with PPI for 2017. https://www.transparency.org/news/feature/corruption_perceptions_index_2016#table↩

7. Namibia has submitted a response to the Panel claiming it has terminated the employment of DPRK nationals.↩

8. Joby Warrick, “High seas shell game: How a North Korean shipping ruse makes a mockery of sanctions,” The Washington Post, March 3, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/high-seas-shell-game-how-a-north-korean-shipping-ruse-makes-a-mockery-of-sanctions/2018/03/03/3380e1ec-1cb8-11e8-b2d9-08e748f892c0_story.html?utm_term=.4794088d2130↩

twitter

twitter