Taiwan’s Former Nuclear Weapons Program: Nuclear Weapons On-Demand

- Paperback edition on Amazon

- E-book versions at Draft2Digital, Kindle, and Nook

- PDF file available on our website

- Clear evidence that Taiwan had a nuclear weapons program spanning two decades that moved forward under the guise of a peaceful nuclear energy program. Taipei excelled at the misuse of civilian nuclear programs and the use of civilian stories to seek nuclear weapons. It implemented capabilities to significantly reduce the time needed to build nuclear weapons, following a decision to do so.

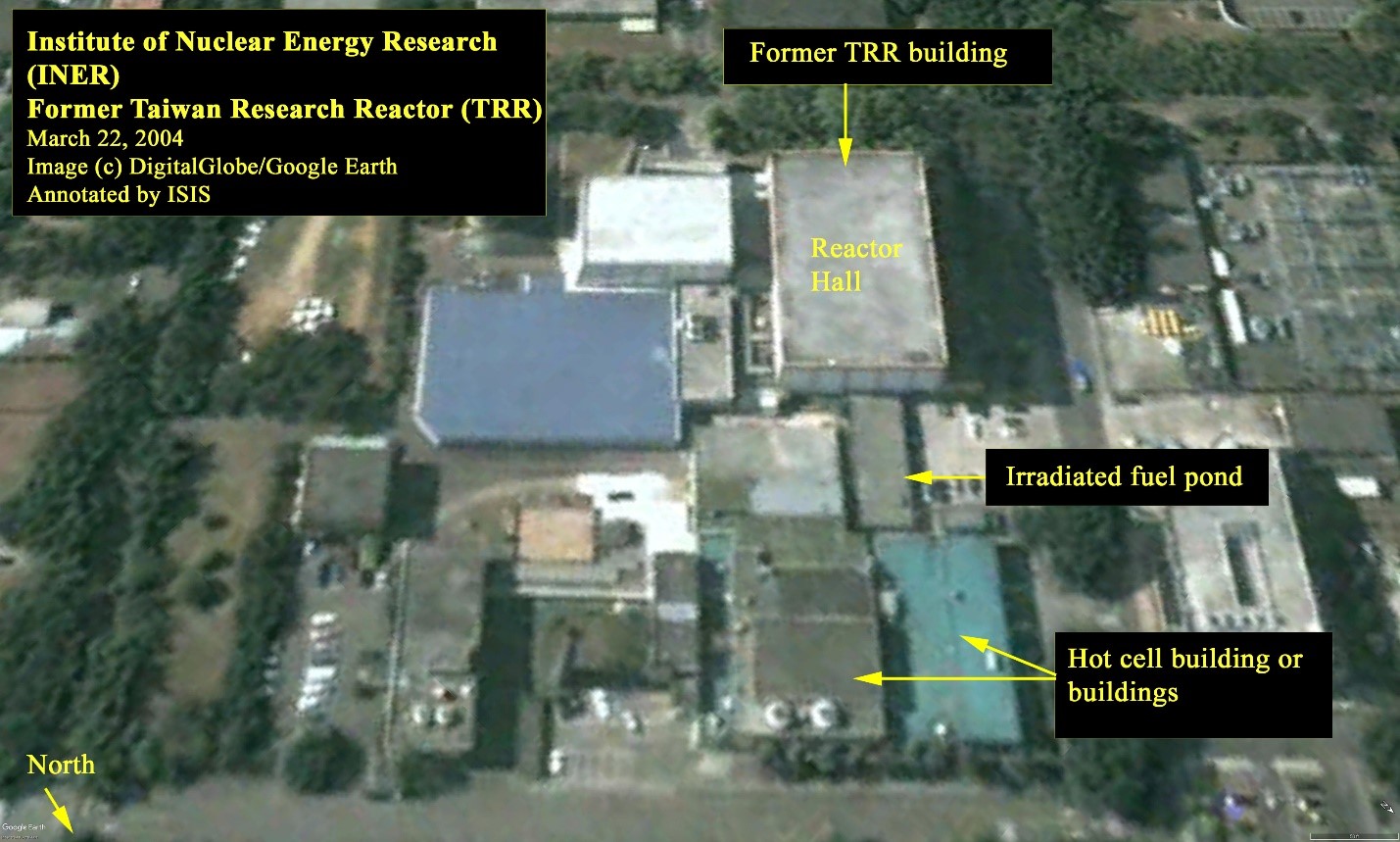

- How Taiwan used the Taiwan Research Reactor (TRR), an ostensibly civilian, safeguarded plutonium-producing nuclear reactor obtained from Canada in the late 1960s as the central feature of its nuclear weapons program, supplemented by multiple secret efforts to establish an ability to separate plutonium from irradiated fuel from the TRR for use in nuclear weapons.

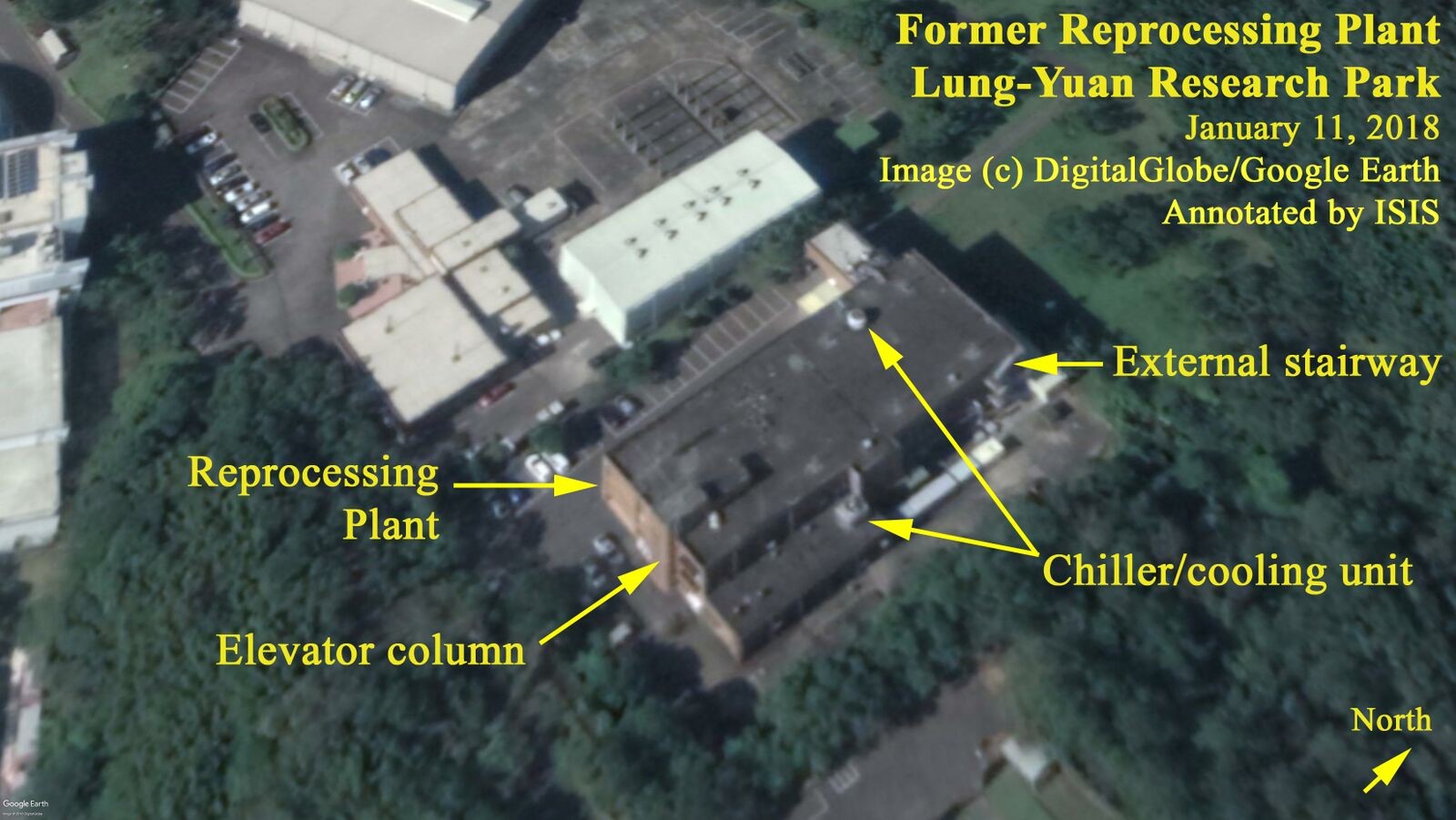

- The book reveals the location and nature of a secret, relatively large plutonium separation plant that Taiwan was building in the 1980s, one of the factors precipitating the United States’ decision to send officials to close the program, including the TRR and all other proliferation-sensitive activities. To render the reprocessing plant unusable, Taiwan required most of the island’s daily concrete production, involving 50 concrete trucks filling the plant with concrete.

- How Taiwan’s nuclear weapons program had to make strides as a largely virtual program and rely heavily on a combination of sophisticated computer simulations and extensive experimentation with high explosives to deliver for the military a nuclear capability ready “on demand.” Taipei could not, for example, conduct an underground nuclear test on such a small island or, for political reasons, over or in the sea. Early on, it decided it would not pursue a full-scale testing option.

- How in 1985, a military strongman named General Hau Pei-tsun ordered Taiwan’s nuclear institute to reach the capability to produce nuclear weapons within three to six months. Taiwan’s military believed it could not hold out more than three to six months following the start of a Chinese attack.

- New information about the activities of Taiwan’s nuclear weaponization program, including the types of computational and simulation efforts ultimately using super computers, high explosive testing, and “cold” nuclear tests. This includes the planned nuclear weapon design to be used by Taiwan, an oval-shaped nuclear core as part of its effort to build miniaturized nuclear weapons.

Figure 1. Decommissioned Taiwan research reactor (grey roof, upper right), provided a source of plutonium for nuclear weapons, albeit in irradiated fuel. Source: Google Earth, 2004

Figure 2. Former secret reprocessing plant that was being built in 1980s to separate plutonium from irradiated fuel for nuclear weapons program. Google Earth, 2018 - The locations and activities of former high explosive test sites used in covert nuclear weaponization efforts.

- Details about Taiwan’s intended nuclear delivery system – a military attack aircraft which would carry a nuclear weapon in a modified fuel tank and drop it over China. The United States successfully prevented Taiwan from building ballistic missiles able to carry a nuclear weapon to China but aided inadvertently in the development and production of this “indigenous” strike fighter.

- More information about a secret 1977 agreement between the United States and Taiwan that restricted Taipei’s problematic nuclear activities, forcing a temporary halt to secret weaponization efforts in order to avoid further diplomatic crisis. It includes details about why this agreement ultimately failed on a technical level to stop Taiwan’s illicit efforts.

- The long history of nuclear inspections by U.S. and International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) officials on Taiwan, including various points of intrigue and key discoveries that were made.

- How scientists and engineers from Taiwan gathered open source and sensitive information critical to its nuclear weapons program through studies abroad or temporary training positions held in nuclear weapon or supplier states.

- How the covert nuclear weapons program illicitly procured sensitive equipment, expertise, and piecemeal capabilities principally from European suppliers, to outfit facilities related to the development of nuclear weapons, such as plutonium separation facilities and plutonium metal fabrication laboratories.

- The fact that Taiwan did not seem to have a strong nuclear strategy in place, or conditions under which it would use a nuclear weapon. It appeared to believe announcing it had a nuclear weapon would deter China from attacking it.

- How an early advisor to President Chiang Kai-shek, Wu Ta-you, tried unsuccessfully to slow the development of a nuclear weapons program on Taiwan in the late 1960s.

- The personal story and actions of informant and patriot, Dr. Chang, who wanted to prevent his beloved Taiwan from going too far and perhaps precipitating a war with China. He risked his life through his aid to the United States and made the sacrifice of moving his family to America in 1988, never again visiting his homeland. An arrest warrant was issued for Chang, and he was treated as traitor by the KMT. The authors believe the ROC government should re-visit this old characterization of Chang’s actions and note his heroism.

- The revelation that Chang was not a U.S. spy in the 1970s, as is commonly believed, meaning that another spy or spies likely provided the United States with information during that time.

- The true non-proliferation success story, never before documented in a long form fashion, about the diplomatic and intelligence efforts of the United States to stop a rather determined proliferator through the use of diplomatic pressure. This pressure campaign and use of diplomatic leverage has numerous lessons to offer for today as the United States deals with new proliferant states such as Iran and North Korea. For example, it suggests that a powerful ally of a proliferant state has more leverage at its disposal to pressure for denuclearization than it may believe. But applying that pressure requires commitment and perseverance.

- Why the United States acted when it did in 1987 to pull the plug on Taiwan’s nuclear program, because President Ronald Reagan and his administration feared that with President Chiang Ching-kuo’s impending death and in the midst of burgeoning plans to hold elections and move from martial law to democracy, General Hau would try to seize control of the government and order the development of nuclear weapons.

- How China and the United States surprisingly engaged in limited information sharing about Taiwan’s nuclear activities at meetings called “Opera Organizations.”

- The role of the IAEA in either missing or detecting proliferation on Taiwan over time, as it reformed its own safeguarding practices and grappled with a weak safeguards agreement in a country that is not technically viewed as a state. The IAEA was instrumental in detecting proliferation-relevant activities at several key points in the crisis. Today, the IAEA may be facing a new safeguards crisis as it fails to adequately push for access and deep inspections of Iran’s nuclear program and risks being marginalized in any denuclearization agreement with North Korea.

- In its dealing with Taiwan, the United States pioneered many of the definitions and practicalities of denuclearization, including the importance of near anywhere, anytime access and defining and excluding a range of dangerous fuel cycle and weaponization capabilities. Although the 1977 secret agreement between Taiwan and the United States had some ambiguities and left room for interpretation by Taiwan, it nonetheless created a strong norm against nuclear weapons and more importantly the means to make them. It also led to the innovation in Taiwan of prohibiting nuclear R&D in military programs and banning classified military R&D in nuclear programs.

- In the last phase of this conflict starting in early 1988, the basic denuclearization steps were accomplished in less than a year, or a few years, if one includes removing the vast bulk of the TRR’s irradiated fuel. In contemplating agreements to limit nuclear programs in countries like Iran and North Korea, the Taiwan case shows that verified, irreversible denuclearization is not only possible, but essential. Otherwise, a nuclear weapons program can or will reemerge. In those agreements, it also makes sense for the United States to push for its own inspection rights, or if that is not possible, as is the case with Iran, the IAEA’s rights need to be substantially strengthened, including guaranteeing timely access to military sites.

- A sobering lesson is the extreme measures Taiwan’s leaders and its nuclear officials used to disguise their nuclear weapons efforts as carefully sculpted civilian nuclear programs or non-nuclear military programs. The IAEA faces similar challenges in effectively safeguarding countries. Iran has pursued a similar strategy by denying its past and possibly on-going nuclear weaponization work and original, planned use of uranium enrichment for nuclear weapons. North Korea may try to keep its uranium enrichment program and reactor programs running in a denuclearization arrangement by claiming that these sensitive facilities have been repurposed to serve a civilian goal, such as enriching uranium for use as fuel in a civil nuclear reactor. But allowing such loopholes would create a dangerous breakout capability. Moreover, agreeing to such a loophole on enrichment makes no sense, particularly given that North Korea’s (or for that matter Iran’s) production of low enriched uranium will be significantly costlier than simply buying the enriched uranium on the global commercial marketplace. Saudi Arabia may try to develop nuclear capabilities by using similar denial strategies. Breaking through such lies is critical.

- How successful denuclearization relies fundamentally on maintaining a strong position against any reprocessing and enrichment capability, and certain types of reac¬tor technologies, such as those involving heavy water-moderated, natural uranium reactors, as one misused by Taiwan. The Taiwan case supports opposing the spread of plutonium separation and uranium enrichment capabilities into regions of tension as a matter of U.S. and allied country policy. Often, these capabilities represent the core of a future nuclear weapons program, regardless of official statements claiming the opposite.

- Denuclearization happened despite Taiwan not resolving its fundamental security conflict with mainland China and not fully trusting the United States to guarantee its survival. The key was U.S. leverage and pressure that Taiwan could not resist. In essence, Taiwan had to choose between relying on the United States or going it alone in terms of nuclear supply and security. Doing so would isolate it from its closest ally, deprive it of enriched uranium fuel for its nuclear power reactors, cut it off from being able to import critical goods for its defense and civil industries, and potentially far worsen its security situation with the PRC. The Taiwan case shows that denuclearization may not depend on resolving a nation’s security concerns prior to it giving up a nuclear weapons program or the weapons themselves.

- One key lesson of the Taiwan case is that it makes sense to develop a strong pressure campaign to address complex proliferation cases. Although few countries are subject to such extreme, external pressure as Taiwan was vis-a-vis the United States, it is worth continuing to establish the most effective ways to increase diplomatic, political, financial, and other economic pressure against countries such as Iran and North Korea until they fully denuclearize, in particular verifiably ending reprocessing, enrichment, the development of dangerous plutonium producing reactors, and nuclear weaponization activities, and verifiably destroying any nuclear weapons in its possession. These proliferant states may in the end opt for conventional forces, economic development, and international and regional integration rather than nuclear weapons, even though not all of their security concerns are resolved. When it comes to U.S. allies, the Taiwan case argues to always link bilateral relations to allies maintaining commitments not to pursue reprocessing, uranium enrichment, or nuclear weaponization. A critical case today for exerting U.S. leverage is Saudi Arabia. It should be expected to agree to forgo reprocessing and enrichment as a condition of U.S. security and nuclear cooperation. If it moves forward with developing these capabilities, the United States should threaten an end to both nuclear and military cooperation.

- For countries like South Korea and Japan, the Taiwan case gives optimism that these countries will refrain from building nuclear weapons, regardless of the fate of North Korean nuclear weapons. Maintaining this status quo requires the United States to tend to its alliances with these countries and engage in regular bilateral discussions over the best way to maintain adequate security. In the case of South Korea, part of that discussion should focus on obtaining commitments not to reprocess or enrich. Although Japan’s reprocessing and enrichment programs are usually exempt from such linkage, given Japan’s large excess stock of separated plutonium, the United States should accelerate discussions with Japan about conditions and means of phasing out its reprocessing program and disposing of its large excess separated plutonium stock.

- The nuclear weapons program on Taiwan is unlikely to ever be reconstituted, even in the face of newly stepped-up threats by the PRC. Too many activities and personnel involved in the program are no longer in place, and the plutonium-producing nuclear reactor at the heart of the controversy was ordered closed by the United States in 1988. Still, the authors caution, with the right pressure and several years, Taiwan could feasibly re-develop its nuclear infrastructure and personnel.