Reports

The Lessons of Nuclear Secrecy at Rocky Flats

by David Albright and Kevin O'Neill

August 26, 1999

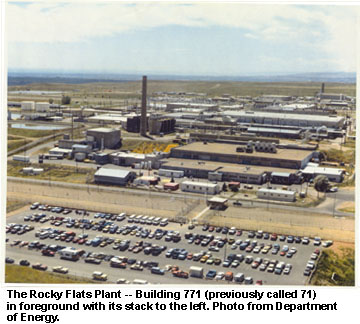

Everyone in the Denver area should be relieved to learn that the general public experienced few health risks due to plutonium releases from the former Rocky Flats nuclear weapons production plant just outside Denver, Colorado. This conclusion is one of the findings of a decade-long study sponsored by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment on releases of dangerous radioactive and toxic materials from the plant. This facility processed plutonium and manufactured nuclear weapons from 1952 until 1989 and is now in the midst of a multi-billion dollar clean up operation.

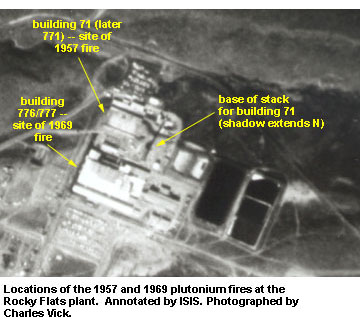

The health department study, to be formally released this week, and a forthcoming book also contain much evidence that radiological catastrophes were narrowly averted at Rocky Flats, particularly during two major fires in the buildings where plutonium was processed. The book, Making a Real Killing: Rocky Flats and the Nuclear West, by University of Colorado professor Len Ackland, reveals how the government and its contractors intentionally kept the public in the dark about the dangers posed by the plant.

The Rocky Flats Plant story should serve as a reminder of how excessive secrecy can increase the health risks to the public. This lesson should not be lost as the Department of Energy (DOE) continues its dangerous and expensive cleanup operations at Rocky Flats and elsewhere.

Both the Rocky Flats study and Ackland’s book show that secrecy worsened many plant safety and health problems, and greatly reduced both the plant management’s accountability and the public’s trust in its words. For example, during much of the plant’s history, it operated without regard to many of the Atomic Energy Commission’s (AEC’s) fire safety standards then in effect.

Following a major fire in 1957, neither the public nor the Coroado state government were informed that a major plutonium release had happened. At the time, the federal government didn’t even publicly confirm that Rocky Flats was handling plutonium.

Lessons about preventing and fighting plutonium fires that could have been learned as a result of the 1957 fire were simply ignored in the climate of secrecy and over-emphasis on production activities. The result was an even worse fire in 1969 that came close to contaminating the entire Denver area with large amounts of plutonium.

Lessons about preventing and fighting plutonium fires that could have been learned as a result of the 1957 fire were simply ignored in the climate of secrecy and over-emphasis on production activities. The result was an even worse fire in 1969 that came close to contaminating the entire Denver area with large amounts of plutonium.

“Rocky Flats created an extremely risky situation for the public,” said Ackland, who heads the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

The AEC’s director of military applications, U.S. Air Force General Edward Giller, told Congress in 1970 that if the fire had not been contained by the heroic actions of the firemen, “hundreds of square miles could be involved in radiation exposure and cleanup at an astronomical cost as well as creating a very intense reaction by the general public exposed to this.”(1) The Colorado health department study confirmed that the fire had been largely kept within the building, therefore resulting in relatively small plutonium releases. According to Giller, however, “If the fire had been a little bigger, it is questionable whether it could have been contained.”(2)

Plant officials shrugged off the plant’s brush with disaster, as Ackland’s book points out. According to the official fire investigation prepared by the AEC, the plant official in charge of nuclear safety emergency planning “advised the [investigation board] that there was no need to have plans for possible off-site damage or personal injuries, since it was not possible for serious off-site contamination to occur, and expressed the view that if such contamination were possible the plant should not be located where it is.”(3)

Following the 1969 fire, plant officials resisted telling the public that there had been releases of plutonium from the plant. Independent scientists started demanding answers and, through their detective work, forced the plant to admit to off-site plutonium releases, safety problems and additional accidents. However, most of the more alarming information remained secret.

Public suspicion about problems at the plant intensified throughout the 1970s and 1980s. In 1989, the FBI raided the plant, suspecting that the plant was wantonly violating environmental laws.

One result of the FBI raid was the creation of a health study, paid for by the DOE, but administered by the Colorado health department. The study team was given the task and, importantly, the resources to get to the bottom of the decades-long puzzle about how much plutonium, uranium, and toxic chemicals were released into the Denver area. The doggedness of the local activists, the media, and independent scientists and researchers was critical in getting this study started and ensuring that it was done in a credible manner.

The DOE helped this study, particularly after Hazel O’Leary became Secretary of Energy in 1993. The DOE subsequently released much previously secret information. This information, needed to estimate historical releases and determine environmental contamination, has been critical to the study’s thoroughness and public credibility. For example, important information about the fires in 1957 and 1969 were declassified for the first time and released to the public.

Such information was declassified without harming U.S. national security. Openness, accountability and national security need not be in conflict with one another. If Congress moves ahead with plans to reorganize the DOE in response to a security investigation at the Los Alamos Laboratory, this effort should not be used as an excuse to wipe out the DOE-wide gains in public accountability and openness that have been made over the past several years.

Openness on the part of the DOE was critical to the success and credibility of the Rocky Flats study. Soon, DOE’s openness will be tested in Paducah, Kentucky, where uranium workers were unknowingly exposed to plutonium during much of the Cold War. Like at Rocky Flats, the public is skeptical of claims that the health risks from plutonium and uranium exposure were minimal.

Although questions will remain about the releases of plutonium, uranium and other radioactive and toxic materials being larger than estimated by the state-sponsored researchers, the health department study showed with the available evidence that the actual damage incurred by people in the Denver area was small. This study did not examine the health effects on plant workers, which is being performed separately.

The most sobering findings of both the health department study and Ackland’s book are the revelations about how close Denver came to a catastrophe as a result of the plant’s practices. Although the releases of plutonium and other types of toxic materials from the site may have been small, the risk to the public was unacceptable when the plant was operating.

Secrecy kept the public ignorant about the Rocky Flats Plant’s true risk. Learning that the bullet missed is scant comfort. Realizing that cleaning up the plant can still pose a risk to the public means that active public oversight remains necessary. Let’s learn from history and avoid more secrecy.

Notes

(1)House Subcommittee on Public Works, Hearings on the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, 91st Congress, 2nd Session, October 1, 1970, p. 295. back

(2)Ibid. back

(3)AEC, Report on Investigation – 1969 Fire, vol. 4, pp. 35-36. back

Related links on the ISIS web page:

twitter

twitter