Updated Highlights of Comprehensive Survey of Iran’s Advanced Centrifuges [1]

Photo Credit: Iran’s AFTAB News

Advanced Centrifuge Deployments

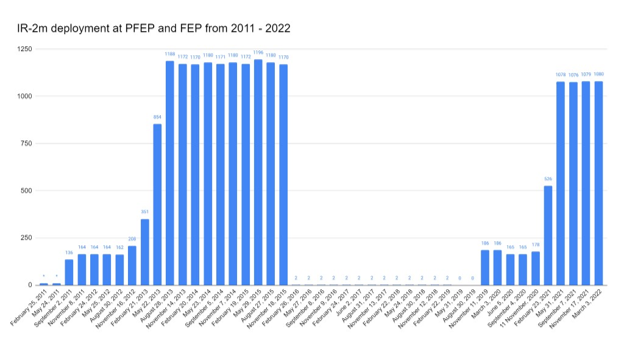

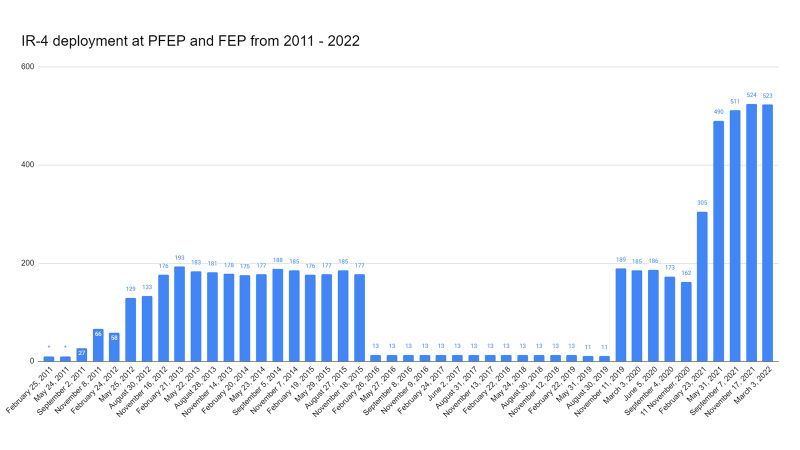

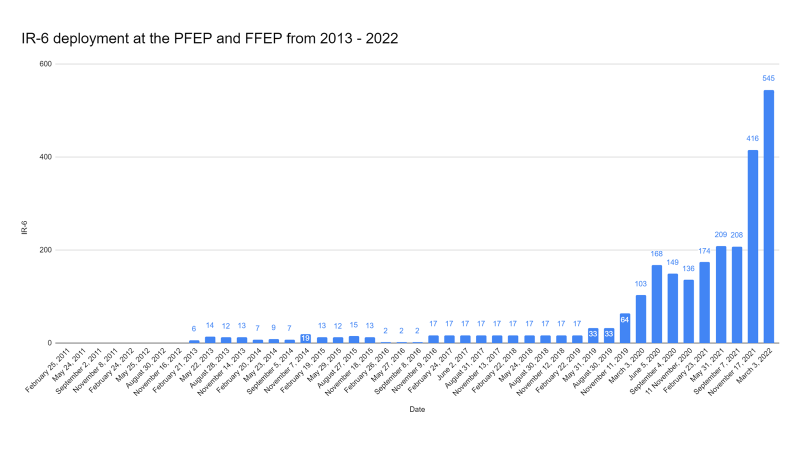

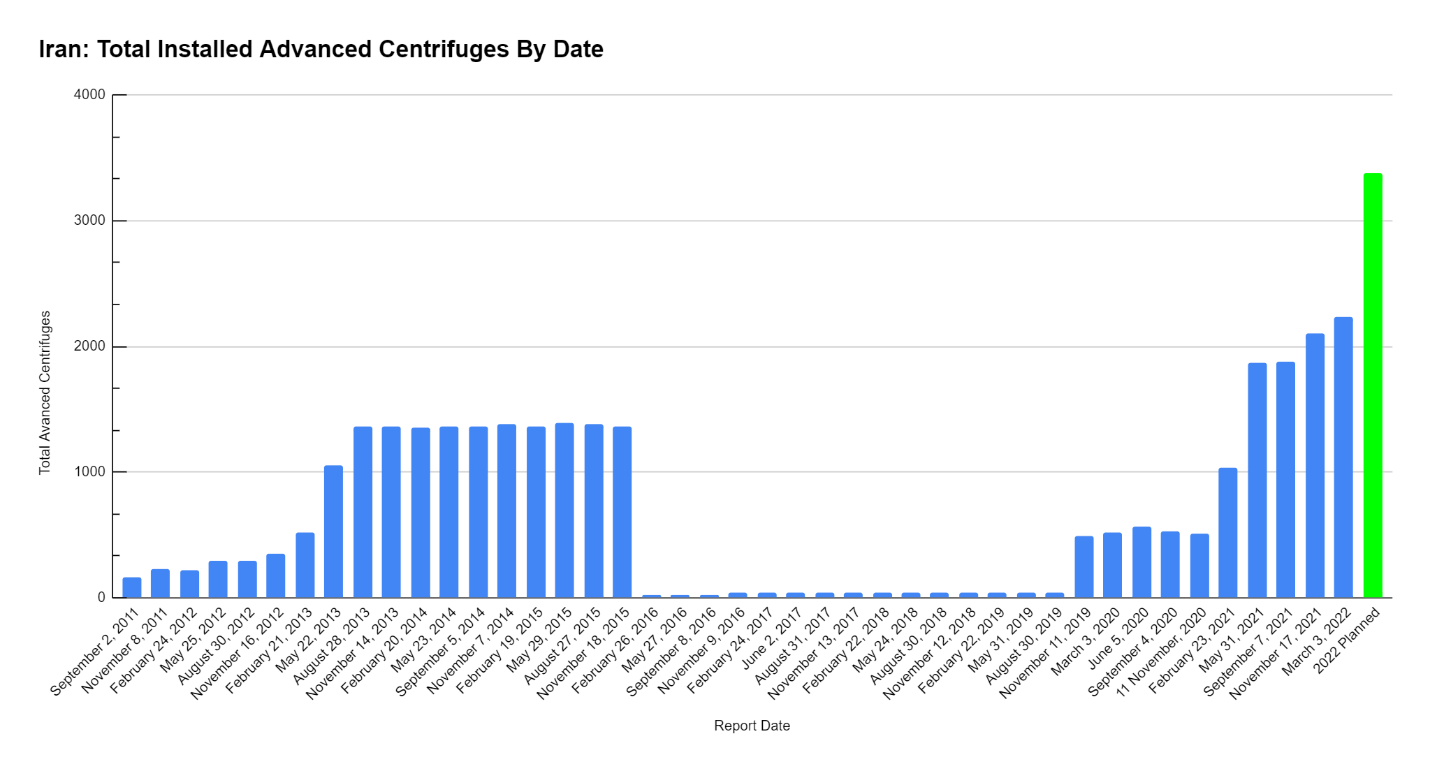

In the last two years, Iran has been deploying advanced centrifuges in violation of the limits in the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), following a lull of three years created by those limits. Starting in late 2020 or early 2021, it dramatically increased the number of deployed advanced centrifuges. Iran has demonstrated its commitment to replace the IR-1 centrifuge with advanced centrifuges, which can produce considerably more enriched uranium.

Figure H.1 shows the number of advanced centrifuges deployed from 2011 onwards through February 2022, with a projection for 2022 based on Iran’s announced plans. Despite the increases in 2021, it is now apparent that Iran’s recent deployments of advanced centrifuges have been slower than planned. One likely cause is the destruction of its centrifuge manufacturing and assembly facilities at Natanz and Karaj. Despite these apparent delays, and ignoring the impact of a new nuclear deal, Iran has not announced any changes to its announced plans, which include the installation of many more advanced centrifuges.

The three enrichment plants where advanced centrifuges have been deployed are the Natanz above-ground Pilot Fuel Enrichment Plant (PFEP), and the much bigger, below-ground Fuel Enrichment Plant (FEP), and the deeply buried Fordow Fuel Enrichment Plant (FFEP).

Figure H.1. Iran’s quarterly number of installed advanced centrifuges at its three enrichment plants, with a multi-quarter projection mid-2022 (last vertical bar). (The number of IR-1 centrifuges are ignored in this graph but see Figure H.3 for a complete breakdown of the situation today.) In April 2021, the Natanz FEP was attacked, affecting half of the IR-2m and IR-1 cascades. The total number of installed cascades remained the same but many of the centrifuges could have been destroyed. Since the attack, Iran likely replaced the broken centrifuges in those cascades, although the IAEA does not report how many centrifuges were replaced.

Figure H.1 shows a steady increase in the number of advanced centrifuges until 2013, followed by a steady level, and then a sharp drop in 2016, when the JCPOA was implemented with a focus on limiting advanced centrifuge research and development, at least temporarily. That number started to increase again in the fall of 2019, after Iran began to violate the JCPOA, but at a faster rate than prior to the JCPOA, reaching unprecedented deployment levels in May 2021 after a sharp increase after late 2020. For almost a year now, the number of deployed advanced centrifuges has exceeded the number deployed prior to the JCPOA and has continued to grow. As of September 2021, Iran had approximately 1889 advanced centrifuges installed at its three enrichment plants, almost all in violation of the JCPOA. By mid-November 2021, this number increased to 2101. By the end of February 2022, this number reached 2232.

These numbers are less than expected based on Iran’s official plans, however. Based on Iran’s declarations to the IAEA and an Iranian nuclear law passed in December 2020, the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI) is expected to install up to another 1149 advanced centrifuges, bringing the projected total to 3381 installed advanced centrifuges.

In the meantime, from November 2021 to the end of February 2022, Iran installed five additional IR-1 cascades at Natanz FEP. This brings the total number of IR-1 cascades installed by Iran to 42 (36 cascades at Natanz and six cascades at Fordow). This progress is in line with the stated plans Iran had previously submitted to the IAEA and shows that Iran is actively working to implement those plans.

Due to difficulties in manufacturing centrifuges, caused mainly by two sabotage events in 2020 and 2021 at its centrifuge production plants, Iran appears to be having trouble achieving the projected number of installed advanced centrifuges. However, Iran appears to be recovering from these attacks and is stepping up its centrifuge production rates. As a result, the country may be able to deploy the projected number, although further delays would be unsurprising. In addition, further installations may be prevented by a new nuclear deal. In the case of a new deal, it may be unclear how many centrifuges were produced in addition to those that were installed.

Key Production-Scale Advanced Centrifuges: IR-2m, IR-4, and IR-6 Centrifuges

The most important advanced centrifuges today are the IR-2m, IR-4, and IR-6 centrifuges. The recent deployments represent a build-back for the IR-2m centrifuge, in contrast to a build-up for the IR-4 and the IR-6 centrifuges.

One way to see the importance of these three centrifuges is to consider that they can replace the IR-1 centrifuges while utilizing the existing cascade piping and feed and withdrawal systems at the Natanz and Fordow sites. In terms of wide-scale deployments, the IR-4 and IR-6 centrifuges appear more important than the IR-2m centrifuge. Iran may have encountered obstacles procuring needed and tightly controlled materials from overseas for the IR-2m centrifuge, limiting its ability to produce it in larger numbers. In contrast, Iran has been more successful evading national and international controls and sanctions with regards to materials needed for the IR-4 and IR-6 centrifuges.

Notably, when Iran started production of 60 percent highly enriched uranium in April 2021, the IR-4 and IR-6 centrifuges were chosen for this task, rather than the ones with which Iran had more operational experience, such as the IR-1 or IR-2m centrifuge. The IR-1 centrifuge has already been used for the production of 20 percent enriched uranium, and the IR-2m centrifuge has been operated in cascades for several years. Further, when choosing to install a cascade at Fordow with sub-headers easily modifiable for producing different levels of enrichment, Iran chose the IR-6 centrifuge.

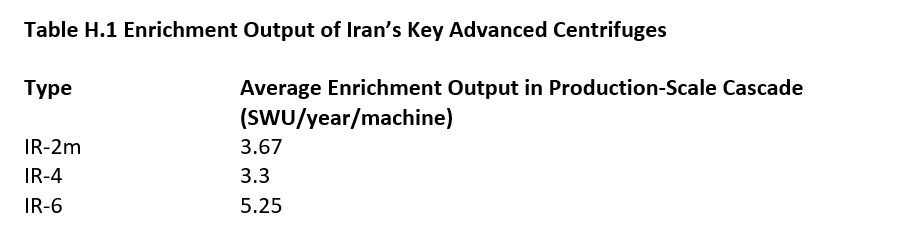

In terms of understanding the impact of these three centrifuges, a key value is their estimated average enrichment output when arranged into cascades of about 160-170 centrifuges, called production-scale cascades, the workhorse for enrichment in Iran. These estimated average outputs are less than theoretical values or single centrifuge measured values because of inefficiencies experienced during larger-scale cascade operation. The enrichment output of the IR-2m centrifuge when operating in a production-scale cascade is estimated in the main report (A Comprehensive Survey of Iran’s Advanced Centrifuges, December 2021, available here) at 3.67 SWU per year; the estimated value for the IR-4 centrifuge in a production-scale cascade is 3.3 SWU per year. The equivalent value for the IR-6 centrifuge is harder to discern from the available information, but an estimated value of approximately 5.25 SWU per year appears justified and reasonable for its average output in a production-scale cascade. In general, these more practical outputs are about 75 percent of their single machine theoretical values given in the main report.2 In practice, lower average values may result, due to centrifuge breakage or during the production of highly enriched uranium, such as production of 60 percent enriched uranium or weapon-grade uranium. Nonetheless, the practical enrichment output of these three centrifuges is far higher than that of the IR-1 centrifuge, which has achieved average production-scale cascade values of 0.6-1.0 SWU per year per centrifuge.

Note: The enrichment output unit in this table should not be confused with Iran’s non-standard enrichment output unit (called in the main report the uranium hexafluoride unit). Iran’s unit is significantly larger than the more conventional unit. An analogy would be using liters instead of gallons in front of a U.S. audience, perhaps with the intention to make a value appear larger than it is.

Advanced Centrifuge Development and Status

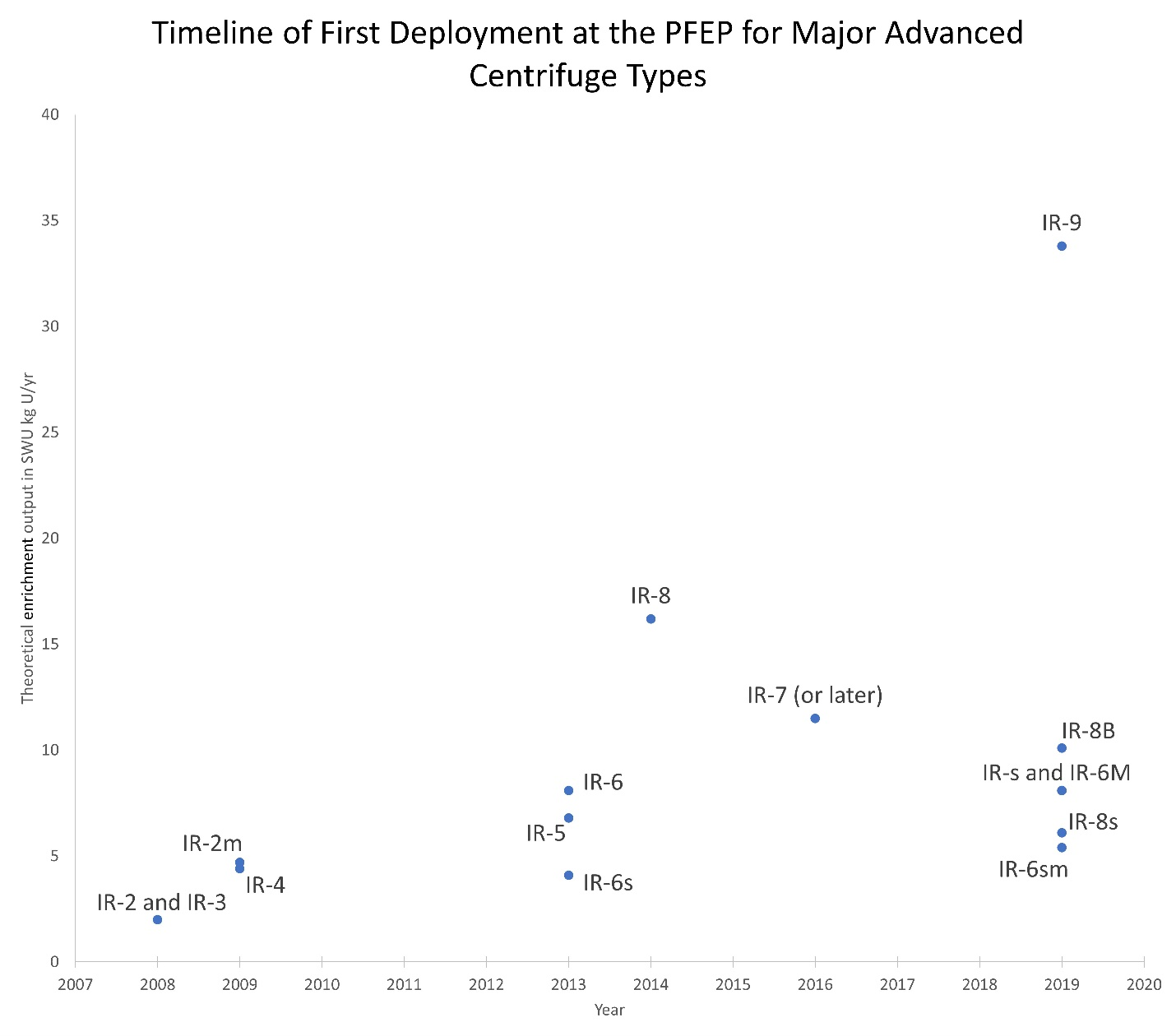

Figure H.2 is a timeline of the deployment of major advanced centrifuge types; the horizontal axis gives the year in which each type was deployed for the first time at the pilot plant at Natanz, starting with the IR-2 and IR-3 centrifuges in 2008. For comparison purposes, the vertical axis lists each centrifuge’s theoretical enrichment output. It should be noted that, when data exist, the output in practice has proven to be significantly less than predicted by these theoretical values. Some centrifuge types are not included in Figure H.2; these centrifuges are included in Chapter 1 of the main report, along with a more detailed discussion about the theoretical and achieved enrichment outputs of each centrifuge type.

Starting in November 2019, Iran demonstrated that it had accelerated its centrifuge research and development by installing seven types of advanced centrifuges in addition to the existing seven types allowed to be deployed under the JCPOA. These seven additional types were not included in Iran’s confidential JCPOA enrichment plan, which projected the deployment of centrifuges up to about 2030.3 The seven allowed ones are the IR-2m, IR-4, IR-5, IR-6, IR-6s, IR-7, and IR-8 centrifuges. The seven not allowed to be deployed under the JCPOA are the IR-3, IR-s, IR-6M, IR-6sm, IR-8B, IR-8s, and IR-9 centrifuges. Of these, all but the IR-3 centrifuge are new models.

Iran’s rapid deployment of many advanced centrifuges in 2019, including many new models, suggests that centrifuge development work continued during the period when the JCPOA was in force and accelerated secretly at least as soon as the United States ended its participation in the JCPOA in May 2018.

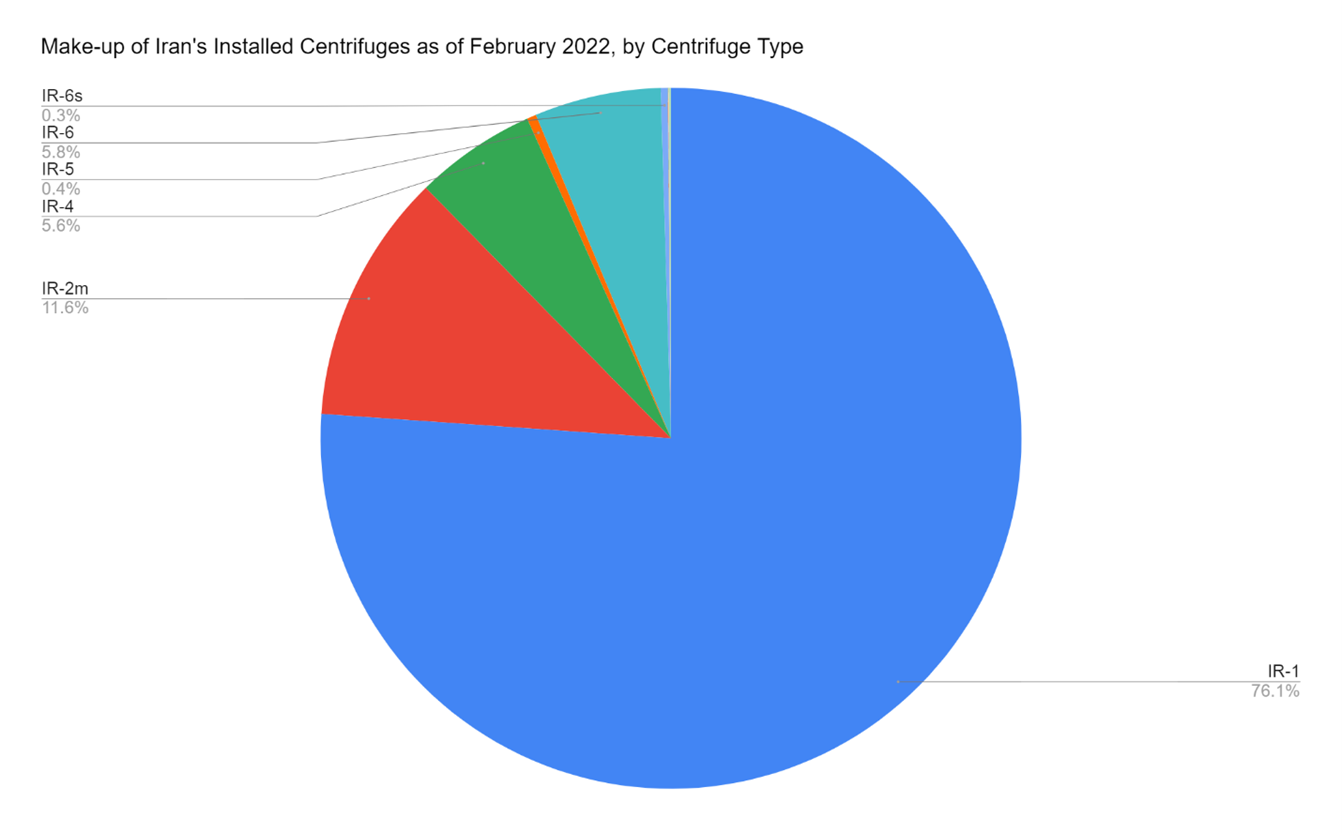

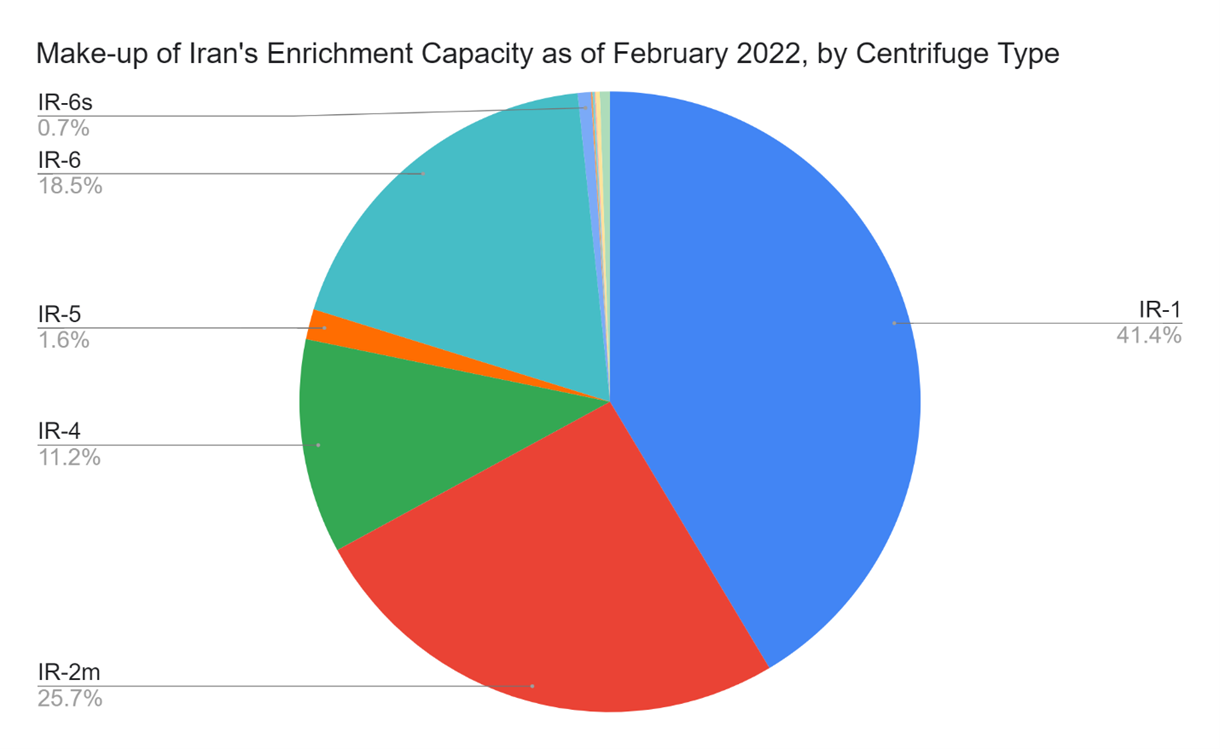

Of the fifteen advanced centrifuge types in Figure H.2, based on the March 2022 quarterly IAEA report, the IR-2m, IR-4, IR-5, IR-6, IR-6s, and IR-s centrifuges were accumulating enriched uranium. The IR-7, IR-8, IR-8B, and IR-9 centrifuges were being tested with natural uranium feed but not accumulating enriched uranium. As of March 2022, not a single IR-2, IR-3, IR-6M, IR-6sm, or IR-8s centrifuge was listed as present in any of the three enrichment plants. The IR-2 and IR-3 centrifuges may have been retired. An additional new centrifuge type, the IR9-1B, is discussed in Chapter 1 (see main report), but it has not been deployed at the PFEP to this date and is not included in Figure H.2. Figure H.3 shows the fraction of each type in a pie chart.

Figure H.2. Timeline of Iran’s deployment of major advanced centrifuge types at the Natanz Pilot Fuel Enrichment Plant, in relation to their theoretical enrichment output, starting with the IR-2 and IR-3 in 2008. Where data exist, the theoretical output proved significantly greater than the practical values Iran achieved when the centrifuges enriched uranium either alone or in cascades.

Figure H.3. The fraction by type and number of Iran’s installed centrifuges at all facilities as of February 2022. The IR-7 (1 installed), IR-8 (1 installed), IR-8B (1 installed), IR-9 (1 installed), and IR-s (10 installed) centrifuge types are represented on this graph, however, the respective counts are too few to be seen.

The JCPOA reduced the number of installed IR-2m and IR-4 centrifuges temporarily, but despite limitations, it only reduced the number of IR-6 centrifuges for a relatively short period of time, and it did not slow Iran’s ability to rapidly produce and deploy advanced centrifuges once Iran decided to stop abiding by the JCPOA limits (see Annex for their historical deployments). Iran has demonstrated its ability not only for a nuclear snap-back but also for a snap nuclear build-up.

In reviewing Iran’s work on advanced centrifuges, the step from single machine tests to small cascade testing appears critical. However, under the JCPOA, this step was allowed from year one of the JCPOA’s implementation for the IR-6 and IR-8 centrifuges, and not enforced sufficiently for the IR-6 centrifuge.

Iran has gained valuable technical knowhow, experience, and advancements in the designing and building of its advanced centrifuges, further enabling a rapid build-back or build-up of centrifuge capabilities. Those gains cannot be reversed or erased, presenting further challenges in seeking to reestablish the JCPOA limits. A sobering finding is that the only way to truly limit centrifuge research and development is to stop it completely, or at least establish a moratorium on it. But the present discussions on a new deal do not appear to include such critical steps.

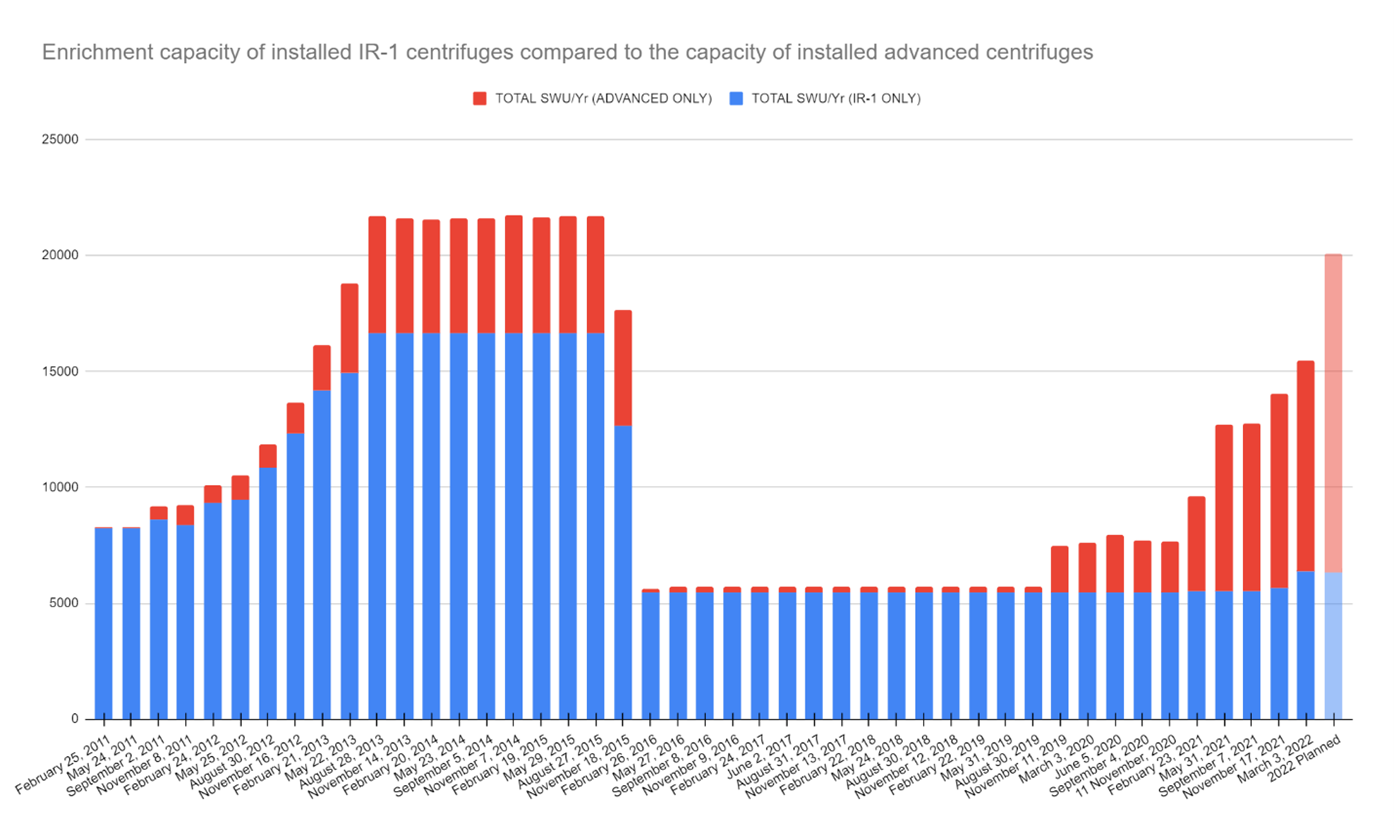

Figure H.4 provides Iran’s total historical theoretical enrichment capacity at Natanz and Fordow, where the IR-1 capacity is in blue and advanced centrifuge capacity is in red. So far, Iran’s current enrichment capacity has not exceeded its total capacity prior to the JCPOA’s implementation but the nature of that capacity is shifting predominately to advanced centrifuges.

Enrichment Output of Advanced Centrifuges

Because of their far greater enrichment outputs, the installed advanced centrifuges, although many fewer in number, began in May 2021 to exceed the enrichment capacity of the several thousands of installed IR-1 centrifuges. As of November 2021, the advanced centrifuges numbered about 2100, or about 34 percent of the number of deployed IR-1 centrifuges at Natanz and Fordow, and they out-produced the 6290 deployed IR-1 centrifuges in enrichment output by about 48 percent. As of February 2022, the advanced centrifuges numbered about 2232, or about 31 percent of the number of deployed IR-1 centrifuges at Natanz and Fordow, and they out-produced the 7110 deployed IR-1 centrifuges in enrichment output by about 41 percent (see Figure H.5 for a breakdown of the total installed enrichment capacity by centrifuge type).

If Iran reaches the projected number of 3381 advanced centrifuges, they will have almost two times the enrichment capacity of the currently deployed IR-1 centrifuges. This advanced centrifuge capacity will also rival all of Iran’s estimated 16,000 IR-1 centrifuges—deployed and stored—with only 21 percent of the number of centrifuges. This comparison ignores any stored advanced centrifuges.

Figure H.4. Total enrichment capacity, by quarter, of the installed IR-1 and advanced centrifuges, with a projection on the far right of the graph.

Figure H.5. The make-up of Iran’s total installed enrichment capacity organized by centrifuge type. Despite the IR-1 accounting for 76 percent of the total installed centrifuges in terms of number (see Figure H.3), it only accounts for about 40 percent in terms of the installed enrichment capacity. The IR-2m, IR-4, and IR-6 make up about 55 percent, and the IR-5 and IR-6s about 2 percent of the installed capacity. The other installed advanced centrifuge types contribute only slightly to the total capacity and are not annotated in the pie chart.

Increasing Advanced Centrifuges’ Enrichment Output

In its development of advanced centrifuges, Iran has lengthened their centrifuge rotor assemblies, boosted their wall speed marginally by increasing the diameter, and changed the rotor tube material to carbon fiber. Carbon fiber allows for higher rotor speeds than the high strength aluminum used in Iran’s IR-1 centrifuge. Iran could have also achieved higher speeds by opting for high strength maraging steel rotor assemblies, as Pakistan did, but Iran appears to have encountered difficulties procuring this material. However, excluding the IR-1 centrifuge, Iran’s enrichment output appears to have increased mostly with length, indicating Iran has had difficulties operating its centrifuges at the higher speeds offered by carbon fiber rotors.

Difficulties with high strength maraging steel appear to have also motivated Iran to develop the bellows, an important component of Iran’s longer centrifuges, from carbon fiber, although carbon fiber bellows are much more difficult to make than ones made from maraging steel. Not unexpectedly, Iran appears to have ongoing difficulties making carbon fiber bellows, continuing to deploy shorter centrifuge models that do not need a bellows in parallel to developing the longer centrifuges. It is also concentrating on deploying advanced centrifuges with only one carbon fiber bellows, a centrifuge design easier to develop than one with two or more bellows.

The IR-s centrifuge bears watching. It is an outlier among the shorter centrifuges, with a relatively high theoretical enrichment output, implying a wall speed more consistent with the potential of carbon fiber rotors. Typically, Iran’s advanced centrifuges have achieved speeds less than optimal for carbon fiber rotors. However, the IR-s may be testing at these higher speeds, say of the order of 700 meters per second. Achieving these higher speeds is difficult but would allow significant increases in enrichment output.

In general, the AEOI has tried to develop many types of centrifuges, far too many for a commercial or economic program. Some of the developments, such as the proudly proclaimed very long centrifuges, appear aimed at impressing a domestic audience and not at large scale deployments in a reasonable time frame. Nonetheless, the strategic nature of Iran’s centrifuge program cannot be ignored.

Advanced Centrifuge Manufacturing

As discussed above, recent attacks on the Natanz Iran Centrifuge Assembly Center (ICAC) and a centrifuge manufacturing plant at a site called TABA (also known as TESA), situated near Karaj, have likely limited, or slowed Iran’s ability to install advanced centrifuges. The ICAC was built to have a capacity to make a few to several thousand advanced centrifuges per year. Iran’s subsequent manufacturing and assembly capacity appears to have been substantially reduced, down to a level of several hundred advanced centrifuges per year. However, Iran has been rebuilding its centrifuge manufacturing capacity, so increases should be expected, absent more attacks or negotiated limits.

Nonetheless, advanced centrifuge production rates are hard to predict, because of unclear Iranian policies on the number produced versus deployed, and less Iranian transparency at its centrifuge manufacturing sites since February 2021. In addition, the sabotage events at Natanz and Karaj have limited the production of centrifuges to an unknown extent. While the November 2021 IAEA report contained no information on the operational status of the Karaj site, the Wall Street Journal reported that the site resumed centrifuge production on a limited scale in August 2021 and accelerated production subsequently, producing “at least 170 advanced centrifuges” by mid-November.4 Shortly after Iran allowed the IAEA to re-install cameras at Karaj in December 2021, Iran announced it was moving the centrifuge production workshop to a new site at Esfahan.5

Further, it is unclear where Iran has been assembling its advanced centrifuges with the ICAC’s destruction. The large, and sudden deployment of various types of advanced centrifuges, however, raises questions as to how, where, and when those centrifuges were produced.6 In an April 2021 MEMRI TV interview, then AEOI-head Ali-Akbar Salehi indicated that a temporary replacement was built. In English subtitles, he is quoted as stating: “Today it was announced that we he had managed to build a hall instead of the one that was lost. This is temporary of course.”7 The subtitles did not identify the location, although it is supposedly at the Natanz site. The Natanz site offers several possible locations for assembling advanced centrifuges on a temporary basis.

In the longer term, Iran plans to assemble centrifuges in a deeply buried underground replacement facility near Natanz, with tunnel construction progressing visibly as of early this year.8 The new tunnel complex will harbor halls more deeply buried than the Fordow uranium enrichment site, itself deeply buried, and features tunnel entrances that appear better protected as well. Nonetheless, the operational status inside the tunnels remains unclear, and it is as yet unknown whether the new site will be ready for operation in 2022. This site is expected to be large enough to produce centrifuges on the same scale as planned for the ICAC, namely several thousand advanced centrifuges per year. In fact, the estimated available floor space underneath the mountain ridge and between the visible tunnel entrances appears to significantly exceed that of the ICAC, leading to concerns that the site may have additional purposes.

Sneak Out in a Clandestine Plant

More powerful advanced centrifuges make it easier for Iran to set up a secret enrichment plant, which would be smaller and host only a fraction of the centrifuges Iran would have needed in 2009, when it was trying to finish up and install IR-1 centrifuges at its secret enrichment plant at Qom, designed to produce highly enriched uranium.9

Since only a relatively small number of advanced centrifuges would be needed to set up a secret and relatively powerful enrichment plant, concern increases about unaccounted production of major parts for advanced centrifuges or whole rotor assemblies. With stocks of near 20 percent and 60 percent enriched uranium (in hexafluoride form) as of February 2022,10 about 650 IR-6 centrifuges would be enough to breakout at a clandestine enrichment site and produce enough weapon-grade uranium for a nuclear explosive in about two to three weeks, where Iran would first use its stock of 60 percent enriched uranium to produce weapon-grade uranium and encounter some delays in shifting from 60 to 20 percent feed. Enough weapon-grade uranium for a second nuclear explosive could be produced by about 1.6 to 2 months after the start of breakout. At this point, all of Iran’s remaining near 20 percent enriched uranium would be depleted. Production of additional weapon-grade uranium starting from 4.5 percent enriched uranium would be considerably slower.

The concern about Iran building another secret enrichment plant will undoubtedly grow with time, absent negotiated limits and far more robust IAEA inspections than have functioned in Iran with or without the JCPOA. After all, the Natanz enrichment plant and the Fordow enrichment plant were started in secret, the latter as part of a covert military program to produce weapon-grade uranium, a facility that went undiscovered for upwards of six or seven years.11 With advanced centrifuges, a secret plant could be smaller, more capable, and harder to discover, and this possibility should not be discounted.

Breakout Timelines Under New Nuclear Deal Limits

Unless compensatory steps are taken, such as destroying rather than mothballing advanced centrifuges, a weaker JCPOA, in essence a new nuclear deal, will not maintain a 12-month breakout timeline to produce enough weapon-grade uranium for a nuclear weapon. If Iran mothballs its advanced centrifuges, timelines of only five to six months are likely.12 A second quantity of weapon-grade uranium could be produced in 8.5 to 10.3 months.13 Thus, instead of breakout taking 12 months, 12 months would be more than enough time to produce enough weapon-grade uranium for two nuclear weapons.

Because of the risk that Iran has accumulated a stock of undeclared assembled centrifuges as well as sensitive centrifuge components, breakout timelines could be further reduced. Some of this uncertainty could be reduced via robust IAEA verification of Iran’s declaration of major components of advanced centrifuges, ensuring it is both complete and correct. So far, Iran has shown no interest in providing such cooperation, and it is unknown if there are any elements in a new deal addressing this key issue. Nonetheless, the IAEA would be expected to attempt to verify Iran’s declaration, at least in terms of the numbers of rotor tubes and bellows made a Karaj, complicating the implementation of a deal but ultimately perhaps providing more assurance of any breakout estimate.

Institute breakout calculations ignore Iran’s demonstrated capability to rapidly build and deploy additional advanced centrifuges, and they do not factor in Iran’s newly gained knowledge, such as its practice of skipping steps in the Khan four-step method of producing weapon-grade uranium. In addition, the calculations ignore the future impact of Iran’s expected, continued construction of new centrifuge manufacturing and assembly facilities at Esfahan and Natanz, apparently allowed under a new nuclear deal. Therefore, calculated breakout times are directly related to the established limits on low enriched uranium stocks and numbers of centrifuges, particularly the number of stored advanced centrifuges. However, Iran’s irrevocable tacit knowledge and new additional capabilities impact the interpretation of calculated breakout timelines by making worst-case breakout calculations more realistic, as they do allow Iran a more assured, perhaps quicker breakout, and in latter months a quicker increase of its centrifuge capabilities. All of this enables Iran to achieve a speedier production of enough weapon-grade uranium for a first, second, third, and fourth nuclear weapon.

Last Word

Iran has made significant progress in building, deploying, and operating advanced centrifuges since 2018, despite suffering significant setbacks due to attacks on its centrifuge production and assembly facilities. However, the effort to return to the status in 2015 or further limit Iran’s advanced centrifuge program has failed. In fact, the new deal being discussed, or at least what is known publicly, would represent a significant weakening of the limits and constraints on advanced centrifuges existing when the JCPOA was implemented in early 2016. Many of these gains, some irreversible and some merely accepted, have occurred during the Biden administration while it was seeking to revive the JCPOA.

Sources

1. David Albright, Sarah Burkhard, and Spencer Faragasso, “A Comprehensive Survey of Iran’s Advanced Centrifuges,” Institute for Science and International Security, December 2, 2021, https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/a-comprehensive-survey-of-irans-advanced-centrifuges/8. ↩2. As discussed in the main report, the associated single machine theoretical values for the IR-2m, IR-4, and IR-6 centrifuges are 4.4, 4.7, and 6.7 SWU/year/centrifuge, respectively. For comparison the single machine theoretical value for the IR-1 centrifuge is 1.4 SWU/year/centrifuge. ↩

3. “Iran’s Long-Term Centrifuge Enrichment Plan: Providing Needed Transparency,”Institute for Science and International Security, Re-released April 25, 2019; Originally issued August 2, 2016, https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/irans-long-term-centrifuge-enrichment-plan-providing-needed-transparency/8. ↩

4. Laurence Norman, “Iran Resumes Production of Advanced Nuclear-Program Parts, Diplomats Say,” The Wall Street Journal, November 16, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/iran-resumes-production-of-advanced-nuclear-program-parts-diplomats-say-11637079334. ↩

5. David Albright, Sarah Burkhard, and Andrea Stricker, “Analysis of IAEA Iran Verification and Monitoring Report - March 2022,” Institute for Science and International Security, March 4, 2022, https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/analysis-of-iaea-iran-verification-and-monitoring-report-march-2022. ↩

6. There is no concrete evidence that Iran has resumed production of IR-1 centrifuges, but recent AEOI statements about deploying six cascades of more powerful IR-1 centrifuges at the FEP raise at least the question whether production of IR-1 components has resumed. ↩

7. MEMRI, “Iranian Nuclear Chief Day Before Natanz Nuclear Facility Blast: We Activated IR-6 Centrifuge Chain,” MEMRI TV Videos, Interview with Ali-Akbar Salehi that aired on channel 1 (Iran) on April 10, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qLmQJOhSusE.Note: In several cases Iranian media mistranslates cascade, calling it a “chain” in English. An Institute translator confirmed the accuracy of the subtitles. In a description accompanying the video clip attributed also to MEMRI TV, a mistranslation appears to occur. According to this description, Salehi said that a hall in the ICAC had been restored where centrifuges are again assembled. He in fact did not make this statement in the video. Moreover, a November 2021 commercial satellite imagery of the ICAC shows its near destruction and no signs of restoration. ↩

8. David Albright, Sarah Burkhard, and John Hannah, “Iran’s Natanz Tunnel Complex: Deeper, Larger than Expected,” Institute for Science and International Security, January 13, 2022, https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/irans-natanz-tunnel-complex-deeper-larger-than-expected. ↩

9. David Albright with Sarah Burkhard and the Good ISIS Team, Iran’s Perilous Pursuit of Nuclear Weapons, (Washington, DC: Institute for Science and International Security, 2021). ↩

10. The March 2022 safeguards report lists 33.2 kg (U mass), or 49.1 kg (hex mass) 60 percent enriched uranium and 182.1 kg (U mass), or 269 kg (hex mass) near 20 percent enriched uranium. The plant is assumed to first enrich the 60 percent to 90 percent enriched uranium and then enrich its entire stock of near 20 percent to 90 percent enriched uranium.↩

11. Iran’s Perilous Pursuit of Nuclear Weapons. ↩

12. Two scenarios are included. The first assumes that only advanced centrifuges deployed as of March 2022 are stored in the event of a new deal and available for breakout, resulting in a total of 12 cascades. The breakout estimate for the first quantity of weapon-grade uranium is 5.5 months, with a second quantity produced 10.3 months after the start of breakout. The second scenario assumes that Iran stores a total of 19 advanced centrifuge cascades, representing its maximal planned deployment of advanced centrifuges. The resulting breakout timeline is 5.1 months for the first quantity of weapon-grade uranium and 8.5 months after the start of breakout for the second one. The breakout calculations assume that IR-6 centrifuge cascades would be installed first, followed by IR-4 and IR-2m cascades, at a total rate of 4 cascades per month. Another two cascades of IR-1 centrifuges would also be installed per month. ↩

13. See Footnote 12. ↩

Annex. Numbers of IR-2m, 4, and 6 Centrifuges, historical deployments, by quarter