Ending the Production of Fissile Material for Nuclear Weapons: Section VI

VI. World Inventories of Plutonium and Highly Enriched Uranium

This section provides information about the amount of plutonium and highly enriched uranium in the world through tables and figures. It draws upon information published in Challenges of Fissile Material Control (Washington, D.C.: ISIS, 1999), which, in turn is based on Plutonium and Highly Enriched Uranium 1996: World Inventories, Capabilities, and Policies (Oxford: SIPRI and Oxford University Press, 1997).

These values are in almost all cases estimates. Public information is scarce about these inventories (see section VII). Only central estimates are provided. The reader is referred to Plutonium and Highly Enriched Uranium 1996 for more details about methodology and uncertainties in these estimates.

Table VI.1:

Estimated Global Fissile Material Inventories,

end of 1997 central estimates in tonnes*

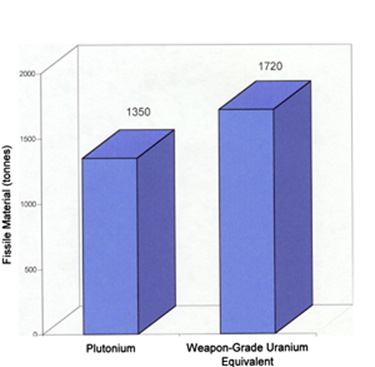

| HEU (weapon-grade uranium equivalent) ** | Plutonium | |

| Military | 1,700 | 250 |

| Civil | 20 | 1,100 |

| Total | 1,720 | 1,350 |

Notes to Table VI.1:

* From David Albright and Kevin O’Neill, eds., The Challenges of Fissile Material Control (Washington, D.C.: Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS), 1999). Central estimates are updates of values in David Albright, Frans Berkhout, and William Walker, Plutonium and Highly Enriched Uranium 1996: World Inventories, Capabilities, and Policies (Oxford: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute [SIPRI] and Oxford University Press, 1997). Excludes highly enriched uranium (HEU) in naval fuel cycles (but includes naval reserves), Russian breeder reactors, and production reactors. Russian breeder reactors use 20-25 percent enriched uranium. If naval and production-reactor fuel cycles were included, it would increase the Russian uranium inventory by about 100 to 200 tonnes of mostly non-weapon-grade material—although Russian naval reactor fuel is significantly more enriched than Russian breeder fuel. Also excluded is the plutonium in the nuclear cores of power reactors. A crude estimate is that at the end of 1997 power reactor cores contained roughly 100 tonnes of plutonium. In addition, civil plutonium inventories have been reduced to account for the decay of plutonium 241. Uncertainties in these estimates are in the range of 10 percent for plutonium and about 20 percent for weapon-grade uranium equivalent.

** Because of uncertainties about the enrichment level of military stocks of enriched uranium, this primer uses the convention of "weapon-grade uranium equivalent." For details see Plutonium and Highly Enriched Uranium 1996. For example, the central estimate for Russia is 1,010 + 315 tonnes of weapon-grade uranium equivalent, as of the end of 1997. A fraction of Russia’s stock is certainly less than weapon-grade, although not enough information is publicly available to derive an estimate of the average enrichment of Russia’s military stock. But assuming the average enrichment of the actual stock is 80 percent, similar to the level of the U.S. HEU stock, Russia would have a stock of about 1,170 + 350 tonnes.

Table VI.2:

Production and Status of Military Stocks of Fissile Material,

end of 1997 central estimates in tonnes*

| Plutonium | Weapon-grade uranium equivalent | Comment | |

| United States | 100 | 635 | production halted |

| Russia | 130 | 1,010 | production halted |

| Britain ** | 7.6 | 15 | production halted; but could purchase HEU from the U.S. |

| France | 5 | 24 | production halted |

| China | 4 | 20 | production believed halted |

| Subtotal | 247 | 1,699 | |

| Israel | 0.46 | ? | production continues |

| India | 0.35 | small quantity | production continues |

| Pakistan | negligible | 0.21 | production likely accelerated in1998 |

| North Korea | 0.03 | — | production frozen |

| South Africa | — | 0.4*** | production halted |

| Subtotal | 0.8 | 0.6 | |

| Total (rounded) | 250 | 1,700 |

Notes to Table VI.2:

* From David Albright and Kevin O’Neill, eds., The Challenges of Fissile Material Control (Washington, D.C.: Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS), 1999). Central estimates are updates of values in Plutonium and Highly Enriched Uranium 1996. Excludes stocks used in naval fuel cycles (not naval reserves) or production reactors or located in reactor cores, but about 20 tonnes of fuel- and reactor-grade plutonium, a fraction of what is in spent fuel, is included. These estimates all have uncertainties associated with them. Unless otherwise noted, these uncertainties are identical to those in Plutonium and Highly Enriched Uranium 1996.

** Recently declassified British figures were published in the British government publication, Strategic Defense Review: Modern Forces for the Modern World. Britain has declared 4.4 tonnes of plutonium to be excess. About 0.3 tonnes of this plutonium is weapon-grade. Britain’s official declared military HEU total is 21.9 tonnes, including HEU dedicated to the naval program. The British government did not release data on the average enrichment of its HEU. Britain’s total inventory was previously estimated at 13.6 tonnes of weapon-grade uranium equivalent, including naval HEU but reflecting losses and drawdowns for nuclear testing. This value appears to be an underestimate of as much as 8.3 tonnes. Not enough information is yet available for a thorough reassessment, but an additional amount appears to have been purchased from the United States under an enrichment services contract in the 1980s and 1990s. It was earlier estimated that about 4 tonnes had been purchased under this contract; now the estimate is closer to 7 tonnes. However, this adjustment still leaves about 4 tonnes of HEU unexplained. Recent British government statements—that HEU was transferred from the Dounreay reprocessing plant to the weapons program—reportedly involve only about 170 kilograms, a quantity far too small to explain the discrepancy. In any case, it is assumed that most of the HEU purchased under the enrichment contract was for naval reactors. But the exact purpose, source, and specific enrichment of the 4 tonnes of HEU remains unclear.

*** Not converted to weapon-grade equivalent. This value is the amount of HEU originally dedicated to the nuclear weapons program. Roughly, 25 percent is HEU enriched to about 80 percent; the rest is enriched to 90-95 percent. South Africa has used an unknown fraction of its stock of HEU from its dismantled nuclear weapons program to fuel the Safari research reactor. South Africa produced more HEU than what was used in the nuclear weapons program.

Table VI.3:

Unirradiated Civil Plutonium,

1996 declarations in tonnes (a)

| Holdings in country | |

| Belgium | 2.7 |

| Britain (b) | 54.0 |

| China | 0.0 |

| France (c) | 65.0 |

| Germany (d) | 5.0 |

| India (e) | 0.5 |

| Japan (f) | 5.0 |

| Russia (g) | 28.0 |

| Switzerland (h) | 0.1 |

| United States (i) | 5.0 |

| Total | 165.3 |

Notes to Table VI.3:

a. From David Albright and Kevin O’Neill, eds., The Challenges of Fissile Material Control (Washington, D.C.: Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS), 1999). Except for India, the source of this information is INFCIRC/549 and its associated declarations. Complete data exist for only 1996. Russian data is for July 1, 1996; the rest is for the end of 1996. The values represent amounts held in each country, not necessarily all unirradiated plutonium owned by a country.

b. Of the total value for Britain, 3.8 tonnes is owned by foreign countries. The total declared value at the end of 1997 is 59 tonnes, of which 6.1 tonnes is foreign-owned.

c. Of this quantity, 30 tonnes is owned by foreign countries. In 1997, France’s stock of unirradiated civil plutonium increased to 72 tonnes, of which about 34 tonnes is foreign-owned.

d. Germany did not declare its stock of plutonium held overseas. This stock is estimated at about 16 tonnes and is included under listings for Britain and France. See Mark Hibbs, "Schroedor will allow reprocessing but push for at-reactor storage," Nuclear Fuel, August 10, 1998. In 1997, Germany’s stock in-country grew by one tonne.

e. Estimated. This value reflects only plutonium separated at the PREFRE reprocessing plant that has not been assigned to the weapons program.

f. Japan also has about 15 tonnes of unirradiated plutonium held overseas.

g. Excess military stocks of up to 50 tonnes of plutonium are not included here.

h. Switzerland’s inventory grew to 0.7 tonnes in 1997.

i. The United States also declared 40.4 tonnes held in the United States but not at a reprocessing plant. This plutonium represents formerly military plutonium transferred to civil use and is part of the roughly 50 tonnes declared excess to military requirements by the United States. As a result, it is not included in this table.

Table VI.4:

Fissile Material Declared Excess

as of July 1997, in tonnes*

| Plutonium | Highly enriched uranium | |

| Britain | 4.4 | 0 |

| China | 0 | 0 |

| France | 0 | 0 |

| Russia | 50 | 500 (assumed weapon-grade) |

| United States | 52.5 | 174 (100 tonnes WGU-eq) |

| Total | 107 | 674 |

| Already disposed of | 0 | 56 |

| Remaining to dispose of | 107 | 618 |

Notes to Table VI.4:

* From David Albright and Kevin O’Neill, eds., The Challenges of Fissile Material Control (Washington, D.C.: Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS), 1999).

Table VI.5:

U.S., Russian Military Stocks of Highly Enriched Uranium, in tonnes

| End of | Total stocks; average 80% U 235 | Weapon-grade equivalent |

| 1994* | 2,030 | 1,750 |

| 1995 | 2,024 | 1,744 |

| 1996 | 2,012 | 1,732 |

| 1997 | 1,985 | 1,706 |

| 1998** | 1,974 | 1,697 |

| Future *** | 1,356 | 1,150 |

Notes to Table VI.5:

* These central estimates are from Plutonium and Highly Enriched Uranium 1996. Uncertainty is about 20 percent.

** As of July 1998.

*** Future estimates reflect the US government commitment to withdraw highly enriched uranium (HEU) from its military inventory as well as Russia’s commitment to blend down HEU (assumed to be all weapon-grade uranium) into low-enriched uranium. The two countries have committed to lowering their stocks by about 547 tonnes of weapon-grade uranium equivalent (or about 618 tonnes of HEU of various levels of enrichment). The schedule is uncertain, but disposal is expected to occur before 2020. Table from David Albright and Kevin O’Neill, eds., The Challenges of Fissile Material Control (Washington, D.C.: Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS), 1999).

Figure VI.6:

World-Wide Plutonium and Weapon-Grade Uranium Estimates,

end of 1997 central estimates in tonnes

Figure VI.7:

World-Wide Inventory of Plutonium, end of 1997 central estimates in tonnes

Figure VI.8:

Unirradiated Civil Plutonium Holdings in Country, 1996 declaration in tonnes

Figure VI.9:

Military Stocks of Plutonium in Nuclear Weapon States, De Facto Nuclear Weapon States, and North Korea, end of 1997 central estimates in tonnes

(portions of British, Russian, and U.S. stocks have been declared excess)

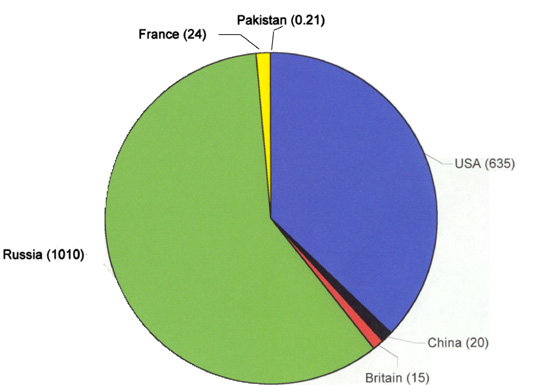

Figure VI.10:

World-Wide Inventory of Weapon-Grade Uranium Equivalent,

end of 1997 central estimates in tonnes

Figure VI.11:

Weapon-Grade Uranium Equivalent in Nuclear Weapon States and De Facto Nuclear Weapon States, end of 1997 central estimates in tonnes

(portions of Russian, and U.S. stocks have been declared excess)

‹ Back