Reports

Revisiting Parchin: With plenty of evidence of past Iranian nuclear weapons activity at Parchin, the IAEA needs to revisit the site

by David Albright, Sarah Burkhard, Olli Heinonen,[1] Allison Lach, and Frank Pabian[2]

August 21, 2017

Fear of derailing the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and facing political pressure led the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in the summer of 2015 to negotiate a problematic arrangement with Iran regarding nuclear weapons development activities at a site at the Parchin military complex. The arrangement, which was negotiated under the Road-map for the Clarification of Past and Present Outstanding Issues regarding Iran’s Nuclear Program, established inadequate rules for on-the-ground investigation and environmental sampling about alleged nuclear weapons-related high explosive work at this Parchin site. Not surprisingly, this weak arrangement, in which the IAEA was limited in its visits and ability to take environmental samples at the site, failed to resolve the issue. Moreover, it has complicated the IAEA’s ability to return to the site to resolve the on-going discrepancies in Iran’s story. Resolving these discrepancies is critical to understanding Iran’s progress on nuclear weapons at this site and elsewhere, assuring the detection of any Iranian attempt to reconstitute its nuclear weapons program, and ensuring that the JCPOA is adequately verified.

Despite years of Iran sanitizing the site and the Iranians taking their own environmental samples, the IAEA nonetheless detected the presence of anthropogenically processed (“man-made”) particles of natural uranium. The IAEA stated that it was unable to make definitive conclusions based on these particles; however, the results suggested that undeclared uranium was at this location, which would potentially be in violation of Iran’s comprehensive safeguards agreement.

For many experts, despite Iran’s on-going denials, substantial evidence exists that Iran conducted secret nuclear weapons development activities at Parchin. The evidence includes the presence of uranium particles, a variety of other evidence of work related to nuclear weapons, and the many suspicious site alterations made by Iran after the IAEA requested access in 2012. It is critical to note that the IAEA has not been able to reach a definitive conclusion and needs to access the site again under greater Iranian cooperation.

Understanding how far Iran went at Parchin is an important part of understanding Iran’s work on nuclear weapons. A comprehensive understanding of this work is critical to setting a baseline for effective monitoring to ensure early detection if Iran resumes work on nuclear weapons. The issue of past activity at the Parchin site is also related to the IAEA reaching a credible broader conclusion under the Additional Protocol that all nuclear material has been accounted for and has remained in only peaceful activities. The past activities at Parchin stand as a roadblock to such a determination. Moreover, the JCPOA, in Section T, Annex 1, bans certain nuclear weapons development activities, some of which are suspected to have occurred at Parchin, and places controls on associated dual-use equipment.3 Section T-controlled equipment was used at this Parchin site, as well as other locations at Parchin, and may still be used at Parchin or at other locations outside of required JCPOA controls.

The P5+1 should require the IAEA to further investigate the Parchin case. The inspection effort should be facilitated by Iran allowing access to key individuals and additional sites, including those near the Parchin high explosive bunker and other associated locations, such as sites involved in multi-point detonator work and manufacturing facilities for explosive chambers. It may well find other important information. The lack of on-going access to Parchin calls into question the adequacy of the verification of the JCPOA and the deal’s long-term utility to deter Iran from obtaining nuclear weapons. Like previous nuclear agreements with North Korea, where the downplaying of IAEA verification helped doom those agreements, the JCPOA currently risks the same fate. It should be noted that North Korea proceeded with undeclared plutonium metallurgy and other nuclear weapons related work outside nuclear facilities subject to IAEA monitoring under the 1994 Agreed Framework, enabling North Korea to continue working on nuclear weapons and to build them more quickly after withdrawing from the Agreed Framework in late 2002.

Background

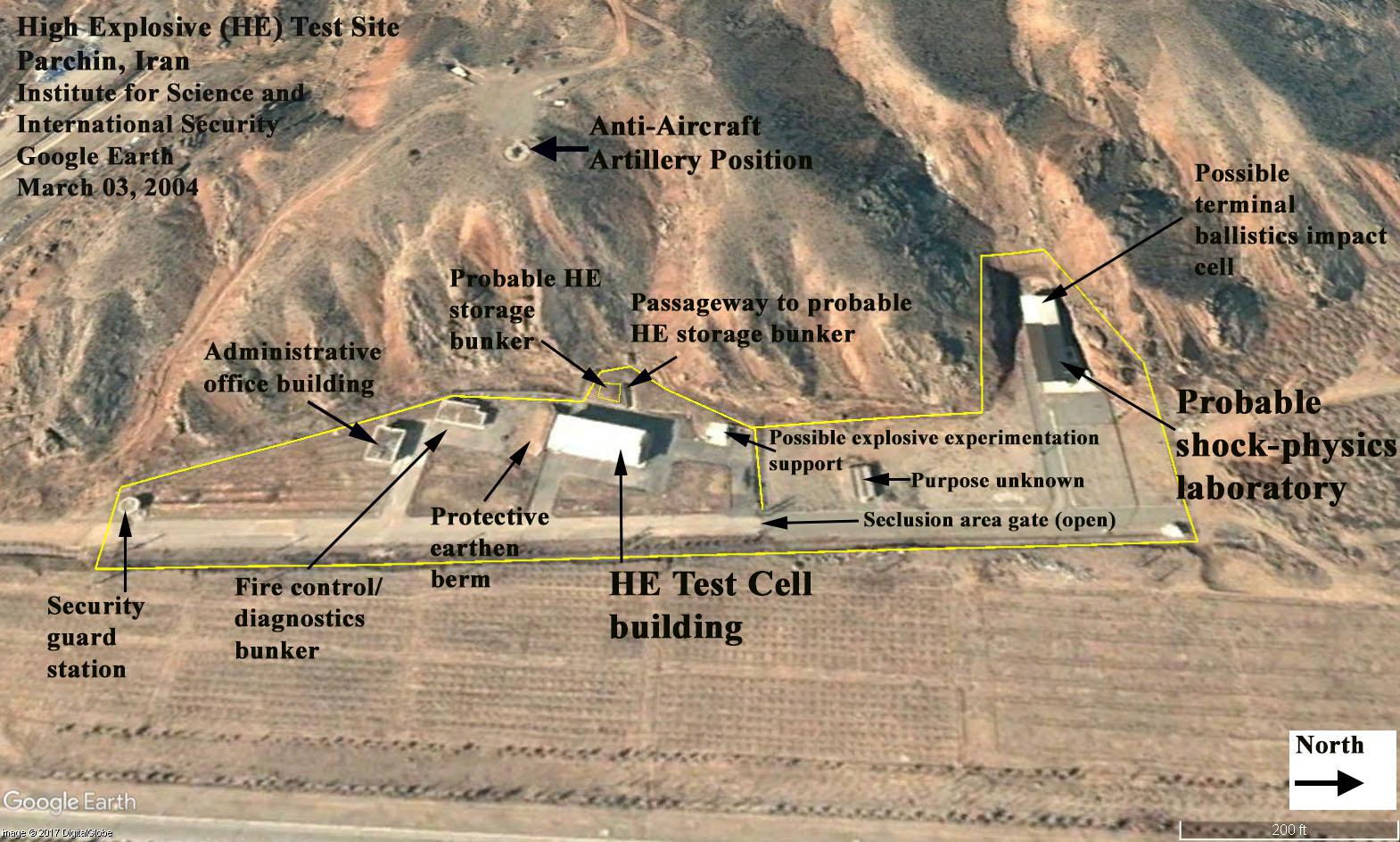

In early 2012, the IAEA requested Iran to grant access to a specific site within the Parchin Military Complex, which the IAEA had evidence contained an explosive chamber. The IAEA had received information indicating that Iran worked on developing nuclear weapons at this site in the early 2000s. Iran refused this access request. Although the IAEA did not reveal the location of this building containing such an explosive chamber, the Institute used imagery to search the Parchin site and located it from the IAEA’s description of the building, namely, a distinctive and unusual berm on only one side of a building (see figure 1). The Institute published the first commercial satellite images of the site in March 2012.4

Later, the IAEA explained, there were indications that Iran had “manufactured simulated components for a nuclear explosive device from high density materials, and that these may have included features relevant to the dynamic compressive testing of the components, i.e. hydrodynamic testing.”5 This testing involved use of a large high explosive chamber and high-speed diagnostic equipment at the Parchin site to monitor the symmetry of the compressive shock. The IAEA’s information indicated that Iran had installed a high explosive chamber and then built the building around it, which was in use until late 2003.

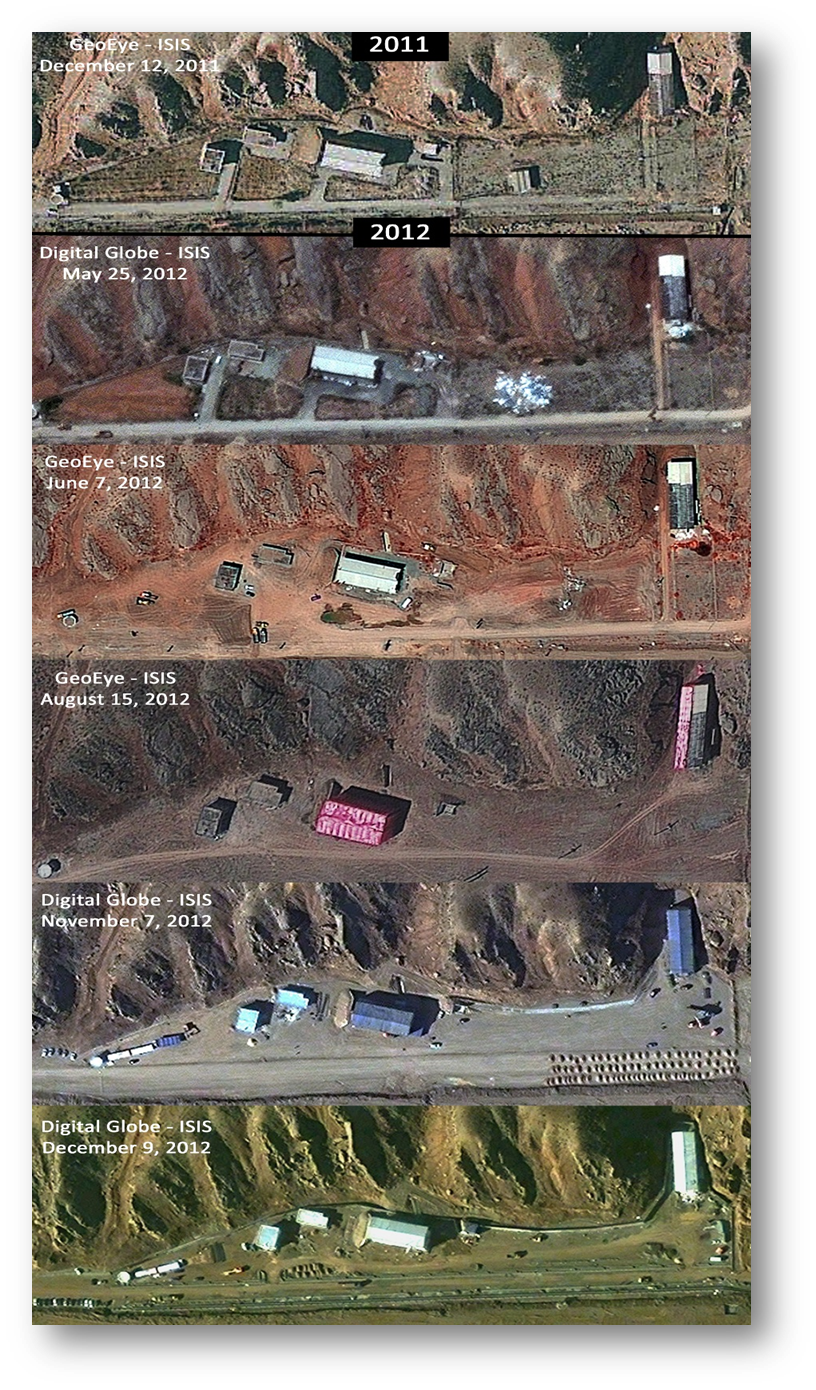

Despite repeated requests by the IAEA and its Board of Governors, Iran denied IAEA inspectors access to this specific site until September 2015. During this more than three-year period, Iran undertook substantial reconstruction and modifications of the site. Figure 1 shows a series of site modifications undertaken at the site after the IAEA’s 2012 request.

The building containing the high explosive chamber underwent almost two years of intense renovation to make it look like it was the same building, but it was essentially a building dismantled and rebuilt in situ. At one point, Iran hung something akin to pink polyethylene sheathing, which some mistakenly called “pink insulation,” during the dismantlement of the interior walls and roofing to contain particulate matter arising during that demolition. The material had a translucent quality not opaque like an insulating material. Moreover, the sheathing was observed over only two buildings–the main explosive chamber building and a second one whose axis is 90 degrees to the chamber building and built into the hillside.6

In addition, Iran removed buildings at the site. After decontamination and removal activities, Iran paved virtually the entire area with asphalt.

In 2015, the IAEA summarized all the changes at the site since it first requested access:7

Since the Agency’s first request to Iran for access to the particular location of interest to it at the Parchin site in February 2012, extensive activities have taken place at this location. These activities, observed through commercial satellite imagery, appeared to show, inter alia, shrouding of the main building, the removal/replacement or refurbishment of its external wall structures, removal and replacement of part of the roof, and large amounts of liquid run-off emanating from the building. Commercial satellite imagery also showed that five other buildings or structures at the location were demolished in this period and that significant ground scraping and landscaping were undertaken over an extensive area at and around the location.

Iran also increased the security of the site by adding walls and taking away penetrable fences. An anti-aircraft artillery piece remains on top of a nearby hill that was put there sometime between 2000 and 2004. There are also rows of guard towers along the eastern perimeter of the site holding the explosive chamber building. There are guard post checkpoints at gates at the north and south entrances to the site. These checkpoints are in addition to several other checkpoints en route to this Parchin site.8

There are also numerous evenly spaced elevated guard towers (every 350 meters) along a road near the site which appears to function primarily as the border patrol road along the river, and the asphalt section stops a mile past the Parchin site near the dam. Overall, the site sits within a high security area with many checkpoints and guard towers. Suggestions that access to the site would be easy are fallacious.

The first image in the series of images in figure 1 shows the site in December 2011 shortly before the IAEA’s request for access in February 2012. Figure 2 shows the same site in 2004. Comparing figure 2 with the first image in figure 1 shows that the site changed little in seven years and highlights that renovations started after the IAEA asked for access.

Iran also increased the security of the site by adding walls and taking away penetrable fences. An anti-aircraft artillery piece remains on top of a nearby hill that was put there sometime between 2000 and 2004. There are also rows of guard towers along the eastern perimeter of the site holding the explosive chamber building. There are guard post checkpoints at gates at the north and south entrances to the site. These checkpoints are in addition to several other checkpoints en route to this Parchin site.

There are also numerous evenly spaced elevated guard towers (every 350 meters) along a road near the site which appears to function primarily as the border patrol road along the river, and the asphalt section stops a mile past the Parchin site near the dam. Overall, the site sits within a high security area with many checkpoints and guard towers. Suggestions that access to the site would be easy are fallacious.

The first image in the series of images in figure 1 shows the site in December 2011 shortly before the IAEA’s request for access in February 2012. Figure 2 shows the same site in 2004. Comparing figure 2 with the first image in figure 1 shows that the site changed little in seven years and highlights that renovations started after the IAEA asked for access.

Parchin Site’s Original Purpose: Unaddressed Buildings

We have annotated the 2004 image (figure 2) to reflect a best estimate of the original purpose of each major building prior to the end of 2003, when the site was reportedly shut down. At least two buildings have not been previously addressed and require further investigation by the IAEA.

It is worth noting that the layout of this site is not random, but follows a clear logic. We assess that the site was well designed for performing contained experiments with high explosives (well diagnosed at close range) in a controlled environment. All the buildings and bunkers in close proximity to the explosive chamber building are protected by berms; some have berms on the sides facing the explosive chamber building.

The explosive chamber building, with two vents visible in some imagery, is located next to a distinctive blast deflection berm, where the building is up against the berm’s flat face, and is likely made from concrete.

Probable High Explosive Storage Bunker

To the west of the explosive chamber building and accessible by an angled concrete-walled passageway is a probable underground high explosives storage bunker. Its foundation is visible in a 2000 image of the site (figure 3). The IAEA did not visit or address this building in its reporting but it needs further investigation.

After retrieving explosives from this bunker, Iran likely prepared the experimental devices in a small building nearby, which had berms on two sides. This building was demolished and rebuilt after 2012.9 It is marked as a possible explosive experimentation support building in figure 2 and was possibly involved in supporting high explosives experimentation activities.

Another building further from the explosive chamber building was dismantled in 2012 and not rebuilt. It is annotated as purpose unknown in figure 2. This building may have been involved in the assembly of devices. In this case, the building would have mated explosives and detonators for later experimentation in the explosive chamber building. This building was isolated enough that if the explosives accidentally detonated, nothing in the proximity would be damaged.

After preparing the high explosive devices, Iran would then have tested the assembled devices in the explosive test chamber using diagnostic equipment subject to section T controls. The control diagnostics were in a building on the south side of the blast deflection berm from the chamber building. There also was an administrative building nearby.

Probable Shock Physics Laboratory

There is one additional, relatively large, rectangular building located at the north end of the site that was built into the hillside that was also not addressed by the IAEA in its reporting. Construction of this roughly 40 meters long building started after that of the chamber building. As was the case with the explosive chamber building, this building was extensively modified after 2012, including modifications that took place under a pink translucent tarp. Although the exact purpose of this building is unknown, the Institute assesses it to have been a research and development test hall linked to nuclear weapons development, probably shock physics experimentation, given the orientation of the long axis of the building backstopped into the hillside – a design that would be advantageous for activities involving projectile impact studies.

The most likely scenario is that this building may have contained a light-gas gun, which would have been useful in conducting experiments with uranium and other materials as part of studying the necessary equation-of-state of uranium. Such experiments, which would have spread uranium, would explain why Iran sought to also sanitize the building. A light-gas gun, possibly in two stages, can be a few tens of meters in length and can generate data that are important to the design of nuclear explosives made with highly enriched uranium. Such experiments yield essential data for uranium metal compressed at high temperatures and pressures. In general, the data are classified and not available from open literature but are critical to theoretical models related to nuclear explosives. It should be noted that South Africa employed light-gas-guns for this purpose for its uranium-based nuclear weapons program.10

The visible signatures suggest that the building was designed to house a light-gas gun, which is, in addition to other uses, essential for nuclear weapons research and development. The building consists of a long hall oriented towards the cut-out hillside, which logically serves as a natural backstop in the event of an accident at the far end. Moreover, that receiving end seems to have involved different construction, as if it held a target chamber cell (for the terminal ballistics). On the opposite end is a personnel access door.11

IAEA Action

Until September 2015, the IAEA had only been able to monitor activities at the site using satellite imagery. The IAEA and Iran worked out a controversial arrangement that allowed for Iran to take environmental samples under IAEA direction in the main high explosive building and for direct visual observation through a ceremonial visit by the Director General and Deputy Director General for Safeguards. Moreover, no sampling was done in the long building built into the hillside, and like other parts of this site, any sampling of soil was severely hampered by the asphalt laid after the decontamination activities.12

IAEA Assessment Explained:13

Notwithstanding Iran’s attempt to contest the IAEA’s imagery-derived analysis by providing Iranian aerial photography, the IAEA used new imagery from various sources to reinforce its previous assessment that a large cylindrical-shaped object was made and installed at the site in the summer of 2000.

The IAEA stated that additional information indicates that this cylinder matched the parameters of an explosives firing chamber featured in publications of a foreign expert, which the Institute identified as ex-Soviet nuclear weapons expert Vyacheslav Danilenko. The IAEA developed evidence that the former Soviet nuclear weapons expert aided in the development of the high-explosive testing chamber inside the building and possibly provided help in using sophisticated diagnostic equipment for testing the spherical symmetry of high explosive shaped charges.14 The chamber dimensions featured in publications of the foreign expert match the dimensions of the foundation that is visible in a GeoEye satellite image of the site from March 2000 (see figure 3 and discussion below). When this GeoEye image was overlaid on Google Earth, the measurements of width and length matched exactly. Moreover, the characteristics of this chamber match those of the Parchin chamber described by the media.

The Institute report Revisiting Danilenko and the Explosive Chamber at Parchin: A Review Based on Open Sources summarizes Danilenko’s writings, which describe a chamber that he designed in 1999 and 2000 that is strikingly similar to the one at Parchin. The IAEA obtained a photo of the chamber installed at Parchin that was built by the Iranian company Azar AB Industries. Based on this information, the IAEA concluded that the chamber at Parchin is very similar to the one designed by Danilenko and described in his 2003 book, titled Sintez i Spekanie Almaza Vzryvom (Explosive Synthesis and Sintering of Diamonds), which a European official said Danilenko wrote based on the lectures he delivered in Iran. In his book, parts of which the Institute has translated from Russian, he states that in 1999-2000, he designed a cylindrical chamber with a radius of 4.6 meters and a length of 19 meters, with a volume of 315 cubic meters, capable of withstanding multiple explosions of devices up to 70 kilograms (see discussion above). The external part of the central section was strengthened with a reinforced concrete square section of 7.6 by 7.6 square meters and a mass of 700 metric tons. Before an explosion, the chamber can be showered with water, and a vacuum can be created.

Danilenko must have known the potential for Iran to apply his expertise to the development of nuclear weapons. According to Danilenko himself, when discussing his work on nanodiamonds in the Soviet Union: “At that time, experiments aimed at methods for diamond synthesis were highly classified because they depended on considerable knowledge applicable to the design of nuclear weapons. For security reasons, the methods were initially contained only in secret reports from the VNIITF [Chelyabinsk-70]. Only in 1987 were parts of those reports forwarded to other members of the diamond club.”15 In addition to having critical expertise on compression experiments and high explosive chambers, Danilenko may have been knowledgeable about gas guns.The visual observation of the inside of the explosive chamber building in September 2015 allowed the Agency to assess that as of September 20, 2015, the cylinder or any associated equipment was no longer present inside the building, and recent signs of internal refurbishment, such as a floor with an unusual cross-section and an incomplete ventilation system, were visible.

Although Iran argued that the building of interest had always been used as a storage for chemical materials for the production of explosives, this purpose is not supported by the results of the analysis of the environmental samples, which did not detect any explosive compounds or their precursors that would have indicated that the building had been used for the long-term storage of chemicals for explosives. In addition, the presence of a blast protective berm on only one side of the building, instead of all four, would argue against such use. Moreover, commercial satellite imagery from 2000, during the construction of the main suspect building, shows the foundation of an adjacent building which was later earth-covered to create a bunker with protected personnel passageway access, is well designed for storing high explosives (see figures 2 and 3). There is no evidence that this probable high explosive storage bunker has ever been removed or modified, and the concrete retaining walls used to create the protected passageway can still be observed. Unfortunately, this bunker was never discussed or viewed by the IAEA during the sole ceremonial visit by the IAEA Director General in 2015.

The IAEA did not address in its reports the purpose and significance of at least two buildings at the site, including the probable high explosive bunker mentioned above in 4) and the long building on the north end of the site that probably was involved in some type of shock physics experimention.

Environmental sampling did identify two particles that appear to be “chemically man-made particles of natural uranium.” However, as noted above, the IAEA stated that number of particles with this composition was not enough to assert the use of nuclear material at the site. Nonetheless, the presence of any uranium particles should have been a “red-flag” necessitating further follow-up investigation.

The IAEA stated that extensive activities undertaken by Iran since February 2012 seriously undermined its ability to conduct effective verification at this site.

Analysis

In its December 2015 report, the IAEA avoided drawing full conclusions about what occurred at the Parchin site, with the result being that the evidence of previous nuclear weapons research development and testing activity by Iran had effectively been swept under the rug, clearing the way for smooth passage of the JCPOA. Iran’s strategy of denial, site modification, refusal of access, and obfuscation successfully worked to prevent the IAEA from making a clear determination. Iran did not address the IAEA’s evidence relating to past nuclear weapons related high explosives testing at Parchin, the help from a foreign expert, and Iran’s subsequent site sanitization efforts. Although the IAEA was able to confirm that the measurements of the explosive chamber featured in publications of the foreign expert did match the size of the foundation at Parchin, overall the IAEA only concluded that the evidence did not support Iran’s claim that the building of interest was used as storage for chemical explosives. At no time did the IAEA raise questions concerning the onsite presence of the probable high explosives storage bunker or the function of the probable shock physics laboratory building.

Despite Iranian efforts to prevent adequate IAEA verification at the Parchin site, the limited environmental samples taken by Iran under the IAEA’s direction identified two particles that appeared to be “chemically man-made particles of natural uranium.” If these samples are accurate, they would offer direct evidence that undeclared nuclear material was at the site and further support that Iran conducted high explosive work related to hydrodynamic testing involving uranium and subcomponents of nuclear weapons.

On balance, the available collected evidence shows that Iran did use this site in the early 2000s for nuclear weapons related high explosives and probably shock physics experimentation. Other than issuing denials, Iran has been unable to refute this assessment. After the request from the IAEA to have access to the location, everything the Iranians have done at Parchin is at its core a blatant deception, including the sanitization, renovations, repainting, and rebuilding at the site to give the outward appearance that little changed. The IAEA concluded that Iran’s statement about the use of the building did not match with the IAEA observations. Due to this, the discovery of anthropogenically modified natural uranium in samples from the site, despite Iranian deception efforts, and the fact that the Iranians did their own environmental sampling, the IAEA needs to finish its investigation of this Parchin site.

The lack of IAEA resolve to revisit the Parchin site appears unwarranted, and serves to weaken the JCPOA and motivates further Iranian obfuscation. It also encourages making military sites sanctuaries, which contradicts the provisions of the comprehensive safeguards agreement and the JCPOA. The Director General of the IAEA should insist on returning to Parchin and take additional samples at the explosive chamber building and at other buildings as well. It should also seek Iranian cooperation to gain access to key individuals and additional sites, including relevant manufacturing sites of the explosive chambers. The Parchin file should in no way be considered closed. Resolving this issue must be part of any effort by the IAEA to reach a broader conclusion under the Additional Protocol and ensure that Section T of the JCPOA is verified.

Figure 1. Chronology of changes at the Parchin site, from December 2011 up to January 2015.16

Figure 1 (cont.)

Figure 1 (cont.)

Figure 2. Parchin site with annotations about the purpose of the buildings related to the site’s function as a nuclear weapons research and development site.

Figure 3. GeoEye satellite imagery showing the foundation where Iran allegedly placed a high explosive (HE) test chamber later in the year 2000. This image also shows the foundation of a building, later earth covered, which was probably used as an underground high explosives storage bunker (see figure 2).

1. Olli Heinonen is Former Deputy Director General of the IAEA and head of its Department of Safeguards. He is a Senior Advisor on Science and Nonproliferation at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies.↩

2. Frank Pabian is a retired Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) Fellow in the Geophysics Group, Earth and Environmental Sciences Division with 45 years of experience in satellite remote sensing. He also served in the 1990s as a United Nations Nuclear Chief Inspector in Iraq for the IAEA.↩

3. Controls on dual-use equipment are in subsection 82.3 of Section T: “Designing, developing, fabricating, acquiring, or using explosive diagnostic systems (streak cameras, framing cameras and flash x-ray cameras) suitable for the development of a nuclear explosive device, unless approved by the Joint Commission for non-nuclear purposes and subject to monitoring.”↩

4. David Albright and Paul Brannan, “Satellite Image of Building Which Contains a High Explosive Test Chamber at the Parchin Site in Iran,” Institute for Science and International Security, March 12, 2012. http://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/satellite-image-of-building-which-may-contain-high-explosive-test-chamber-a/8↩

5. Director General IAEA, Final Assessment on Past and Present Outstanding Issues regarding Iran’s Nuclear Programme, GOV/2015/68, December 2, 2015, paragraph 47. http://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/IAEA_PMD_Assessment_2Dec2015.pdf↩

6. Please see: http://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/new-phase-of-suspect-activity-at-parchin-site/8, http://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/Parchin_March2000Image_10April2012.pdf, http://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/revisiting-danilenko-and-the-explosive-chamber-at-parchin-a-review-based-on/8, and http://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/Revisiting_Parchin_September_11_2015_Final.pdf↩

7. Director General IAEA, Final Assessment on Past and Present Outstanding Issues regarding Iran’s Nuclear Programme, GOV/2015/68, December 2, 2015. http://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/IAEA_PMD_Assessment_2Dec2015.pdf↩

8. We identified at least three checkpoints north of the site. There are also three major checkpoints to reach the site from the south side through the main Parchin complex. See figure 3 in http://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/Revisiting_Parchin_September_11_2015_Final.pdf.↩

9. See http://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/Parchin_site_activity_May_30_2012.pdf↩

10. See chapter 2 in http://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/RevisitingSouthAfricasNuclearWeaponsProgram.pdf↩

11. See for example https://www.llnl.gov/news/100th-shot-llnls-gun-desert, Livermore Laboratory Nevada Gas Gun, and https://e-reports-ext.llnl.gov/pdf/325288.pdf. Also, http://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/RevisitingSouthAfricasNuclearWeaponsProgram.pdf↩

12. For more information on the issues relating to the visit and environmental sampling process see David Albright, Olli Heinonen, and Serena Kelleher-Vergantini, “IAEA Visit to the Parchin Site,” September 22, 2015, http://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/IAEA_Visit_to_the_Parchin_Site_September_22_2015_Final_1.pdf.↩

13. Director General IAEA, Final Assessment on Past and Present Outstanding Issues regarding Iran’s Nuclear Programme, GOV/2015/68, December 2, 2015. http://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/IAEA_PMD_Assessment_2Dec2015.pdf↩

14. See David Albright and Robert Avagyan, “Revisiting Danilenko and the Explosive Chamber at Parchin: A Review Based on Open Sources,” Institute for Science and International Security, September 17, 2012, http://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/revisitingdanilenko-and-the-explosive-chamber-at-parchin-a-review-based-on/8, and Mark Gorwitz, “Revisiting Vyacheslav Danilenko: His Origins in the Soviet Nuclear Weapons Complex,” Institute for Science and International Security, September 17, 2012, http://isisonline.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/Gorwitz_Revisiting_Vyacheslav_Danilenko_17Sept2012.pdf.↩

15. From Danilenko, V.V. (2004). On the History of the Discovery of Nanodiamond Synthesis, Physics of the Solid State, 46(4), 595-599. See also http://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/revisitingdanilenko-and-the-explosive-chamber-at-parchin-a-review-based-on/8.↩

16. Originally published in David Albright and Serena Kelleher-Vergantini, “Parchin in the IAEA’s Final Assessment on the PMD to Iran’s Nuclear Program,” Institute for Science and International Security, December 3, 2015, http://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/parchin-in-the-iaeas-final-assessment-on-the-pmd-to-irans-nuclear-program/8#images↩

twitter

twitter